The very best fighters, and even those who aren’t so great, often have a healthy regard for their own ability. It’s a type of radiant self-confidence, which provides a form of protection in the ring just as great as a well-timed slip or a subtle parry. Even at the age of 70, former lineal, WBC and IBF heavyweight champion Larry Holmes (69-6, 44 KOs) justifiably has self-confidence in abundance. “When you talk about great fighters, you’ve got to mention Larry Holmes,” he told Boxing Social. “When you talk about Joe Louis and Floyd Patterson and Rocky Marciano, you’ve got to put Larry Holmes down there.”

Although jovial and warm, Holmes has lost none of the combative elements which saw him defend his title 20 times and rule over the heavyweight scene from the late ‘70s to the mid-80s. It’s a story, like many in boxing, which started in adversity. “I dropped out of school, man. I’m a drop out. Nothing doing [when I’d left]. So, I go to the local gym and learn how to fight,” he said. “You don’t need an education to learn how to fight. All you need is the education to throw a right hand a left hook. That’s all… I wanted to make some money for my family. And I became very good at it.”

Holmes was, indeed, very good at it, mixing an imposing physique with intelligent footwork and a jab vaunted as the best seen in the heavyweight division in any era. A Holmes jab, even 30 years later, is a sight to behold. Authoritative, quick and accurate. Both a set-up to a power punch whilst capable of causing major damage itself, it was the foundation of a Hall of Fame career.

But there was no real secret to how it was obtained, according to Holmes. “I worked on my jab, I practiced it, I perfected it,” he said. “First thing you learn when you go into boxing is, you learn how to jab. You learn how to block… If you don’t block, you get hit, and it hurts! And it took me all the way.”

Holmes’ hard work and natural aptitude were supplemented by becoming a go-to sparring partner to a who’s who of elite heavyweights from the 1970s. “I worked out with Muhammad Ali. I learned a lot from him. But anyone who needed some work, I worked with them. Joe Frazier, Earnie Shavers, guys like that,” said Holmes. “I’d try to learn something from all of them. A little bit from Ali, a little bit from Shavers. You have to learn how to jab when you fight the big guys like Shavers and [Ken] Norton.”

In addition to world class sparring, Holmes also had a brain trust of three of the sharpest trainers and cuts men ever in his corner: “I trained with Eddie Futch, Ray Arcel and Freddie Brown. Those were the best guys in boxing when it came to training guys. [But] I really learned how to box from Muhammad Ali,” he said.

Holmes’ schooling saw him rise through the ranks before he defeated Ken Norton in 1978 for the WBC crown. Boxing Social asked how it felt to be a world heavyweight champion; an experience, even in a diluted era, very few will ever experience. Yet what motivated Holmes most was a desire to prove others wrong.

“Winning the heavyweight championship of the world was great,” Holmes said with evident pride, “because there’s some people out there who said I wasn’t going to be anything, I can’t make it, I wasn’t good, I can’t fight, I’m a copy of Muhammad Ali, I can’t go nowhere. So I thought, ‘watch me’. Then I became the heavyweight boxing champion of the world. And the undefeated champion of the world for seven years. And people looked at me, and they knew everything they thought I couldn’t do, I done it.”

Holmes is the link between the heavyweight ‘golden age’ of the ‘70s and the chaotic ‘90s scene. But for some time, it left Holmes severely underrated and underappreciated, and it’s evident when speaking to him that he still feels that. “I defended my title and [the critics] had nothing to say then. Even now, people don’t want to give me my credit. I was one of the greatest fighters out there,” he stated.

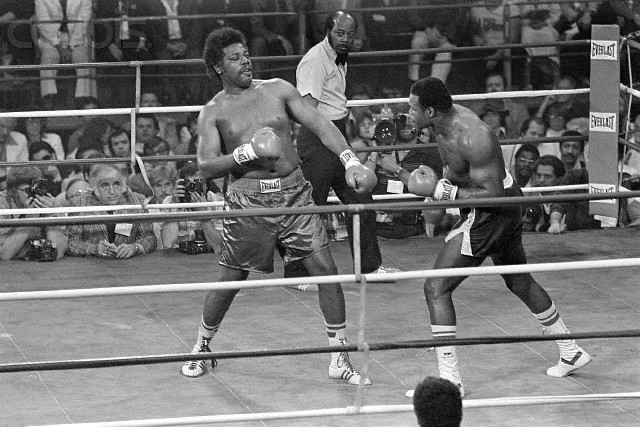

One of the biggest indicators of Holmes’ greatness was his ability to overcome adversity and retain his composure inside the ropes. Nothing defined that more than his Lazarus-like rise from the canvas after being floored by an Earnie Shavers right hand in the seventh round of their WBC title fight in 1979.

“Shavers hit hard. I mean, real hard. Twenty years later, I can still feel the punch,” said Holmes. “He was one of the hardest punchers in the world. He hit me and knocked me down and I beat him. I fought him twice, and beat him both times. And nobody wanted to fight Earnie Shavers. Ken Norton did not want to fight Earnie Shavers. Muhammad Ali did not want to fight Earnie Shavers. Larry Holmes said, ‘bring him on. I’ll fight anybody’.”

Holmes attributes Ali’s later troubles in life to the power of Shavers. “The trouble Ali had, Shavers did that,” he said. “He beat him up, hurt him. Your head can’t take that. Ali did. I didn’t take all them punches.”

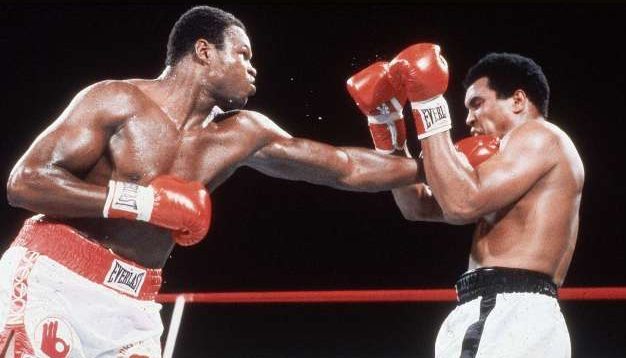

Ali was a figure Holmes mentioned often in our conversation, and the former champion holds the distinction of being the only fighter to stop ‘The Greatest’. Yet it was a diminished version and, watching the fight back, it’s clear that Holmes was reluctant at times to fully unleash his punching power. “Ali was my friend, too,” Holmes explained. “I wasn’t just his sparring partner. I didn’t want him to get hurt, I could see how he acted when I hit him, he was hurting.”

I asked how it felt to beat a fighter so revered, yet past their peak. “I was happy but I was not happy, because I didn’t want to beat him up like that,” he said. “But I had the problem, if I beat him they’d say he was old and, if I didn’t, they’d say I never had it anyway. You do what you gotta do to become champion, and people still put you down.”

Although Holmes is still self-confident, he was eager to set the record straight about the rivalry between he and Gerry Cooney, which was promoted along explicitly racial lines. “It made me feel uncomfortable… they can’t put me as racist,” he said. “Half my family is white… I’ve got nieces and nephews who are white. I have no discrimination. We can’t help who we are. When you come out of that womb, you don’t know if you’re white, black, green. God bring you here and put you down, and you make the best of it as you can.”

Holmes was on the cusp of equalling Rocky Marciano’s vaunted 49-0 record when he came up against Michael Spinks, the Hall of Fame light-heavyweight in 1985. He seems at peace with that decision loss, although he disagrees with the outcome. “It doesn’t matter what they said about that [fight against Spinks]. We know who won the fight,” he said. “Even though I didn’t fight my best fight, I won the fight. I speak to Michael when I see him, I say, ‘what’s up?’ I don’t hate Michael Spinks. Records are there to be broke.”

Following the Spinks fight and a rematch which also went against Holmes, the ‘Easton Assassin’ hung up the gloves for two years before returning to fight a peak, 22-year-old Mike Tyson. “Mike Tyson would have been easy for me to fight [early in my career]. I was out for two years and I came back, and I wasn’t in shape to fight Mike Tyson,” Holmes reflected. “He was just a good puncher. He wasn’t a boxer. He didn’t know how to box. He knew how to punch. No punchers were going to get me [in my prime]. Shavers was a puncher and he didn’t get me. I fought Tyson the way I thought I should, but my arm got caught in the ropes. I was setting him up. It was going his way that day….but no, he’s nowhere near me in the greats.”

Discussions of different generations of heavyweights led us to the current crop of champions and contenders in the division, but Holmes seemed unimpressed. “They couldn’t fight me. I’d have kicked their ass. I’d have knocked them out,” he said. “Come on. They can’t take a punch… they’re amateurs. To me? They’re amateurs. To Ali? They’re amateurs. To Ken Norton? They’re amateurs. To Joe Frazier? They’re amateurs. To us, they’re kids. They can’t fight. They didn’t learn how to fight. We learned how to fight.”

I pressed Holmes on why he felt the standard had declined and he traced it back to work in gyms, pointing out that: “You go to the gym today and you see a lot of kids trying to box. The person teaching them how to fight might never have had a fight. Now how can you teach me something you never done yourself? How can they show me a fight?”

Would Holmes, articulate and knowledgeable, be able to train a young fighter? He seemed more than willing to help. “I would help then out. I would see what they got,” he said. “If they can’t fight, I’d say, ‘hey man, you should get a job, because boxing is not for you!’”

Regardless of exactly how Holmes is viewed by today’s boxing fan, be it underrated or overrated, there’s no disputing the indelible mark he left on boxing’s glamour division. Indeed, in this writer’s own humble opinion, he certainly belongs in the upper echelons of any all-time list.

“Even today, my record speaks for itself.” Holmes said as we signed off. “How many fighters can take my record? How many?”