Boxing’s purpose remains turning young people’s lives around

If boxing has one purpose, it’s not to produce superstars, but to steer the lives of anonymous adolescents in crime-ridden neighbourhoods to a safer passage through discipline, respect and the dedication learned in a sweaty boxing gym. Ironically, it’s the brutal nature of the craft that attracts these kids to pugilism in the first place – and it’s this primitive format of combat that often saves them from a life on the fringes of society.

It’s been widely reported that youth crime in the UK and South East is at a particularly high level. Commentators are worried about knife crime and gang warfare. Whether one suggests increased policing, harder sentences, banning of music genres, a public health-approach or a combination of factors – the reality is that a large-scale problem is hardly ever tackled by one solution. But many experts across the political and social spectrum are advocates of boxings rile in tackling this frightening problem.

The sport has over time offered a way to engage young people and helped them turn their lives around. It’s impossible to quantify how many lives boxing has saved. However, it’s a widely accepted notion that despite the violent nature of the sweet science – at any level boxing combats youth delinquency. The question is why does fist fighting in the ring have this impact, more so than other leisurely activities?

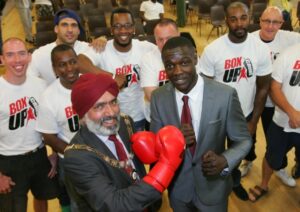

Stephen Addison, the founder of Box Up Crime, a boxing scheme aiming to encourage teenagers away from gangs and crime, has a unique view point on this issue.

“Boxing is a sport where there’s a lot ego attached to it, there’s a lot of identity attached to it, a lot of character and personality attached to it. All of these things are stuff that young people look for in negative places – in gangs and drug dealing – if you can provide that same thing that young people look for in a better [and] more constructive facility like boxing you are answering their problems,” Addison said.

The anti-knife crime activist’s initiative helps over 800 young people on a weekly basis across London and even in Switzerland through boxing, mentoring and educational initiatives. Since 2013 Box Up Crime have reached and impacted the lives of 4,000 young people. With aspirations to expand the programme to the U.S.A. and Africa. Beyond boxing the charity helps adolescents pursue entrepreneurial paths and are in the process of setting-up a boxing school for young people kicked out of mainstream schooling.

Dr Mark Prince OBE, former light heavyweight World title challenger, believes that the notoriety of being labelled a boxer and the street credit gained through this noble art attracts young people to the sport. Acting as a substitute more deviant activity, he said:

“They [young people] understand if I box people respect me. A lot of these guys – that’s what they want out of the streets, that’s why they join gangs. That’s why they carry knives. Because the ethos or the mindset out there [on the streets] is that they will fear me, they will respect me, people will look up to me as I’m a “badman”. Boxing is the epitome of being fearless, tackling issues and being able to improve as a person, because everyone respects fighters.”

Prince was once involved in the ‘street life’ himself, but boxing helped turn his life around. He reached the highest echelons of the sport and the former WBO light heavy world title challenger retired with a 23-1 record. Earlier this year he was awarded an Order of the British Empire (OBE) for his work tackling knife crime through his charity the Kiyan Prince Foundation.

The former fighter and eloquent motivational speaker continues to dedicate his life to engaging and inspiring young people (nearly to date 90,000) since his son, Kiyan, at age 15 was tragically killed when he was fatally stabbed in 2006, while intervening to prevent the bullying of another boy. Kiyan Prince was a highly touted football talent, who played for Queens Park Rangers at youth level.

Dr Deborah Jump, Senior Lecturer in Criminology at Manchester Metropolitan University, is currently finalising a book on this very topic titled ‘The Criminology of Boxing, Violence and Desistance’, which will be published towards the end of the year. Her academic research into crime and boxing points that the sport is a great hook for change.

“It [boxing] allows young men to disengage from crime while still saving face. It also allows for young men to feel masculine in a way that other sports may not,” according to Dr Jump.

“Boxing provides attachment figures in the shape of coaches and peers, and the positive role models fostered in the gym environment can contribute [when delivered carefully] towards a change in negative attitudes towards crime,” the Senior lecturer added.

Time spent training is a positive activity that doesn’t involve deviance and importantly it’s an environment with strong role models and a range of characters. This is particularly important for young people, who have dropped out of mainstream education or who lack role models in their households. These facilities stuck under railway arches or sketchy industrial estates offer a place where a teacher, in the form of a coach, not only instils discipline, but gives a lesson in respect, accountability and a work ethic.

Boxing builds character and can help shift preconceptions

Character traits learned through boxing transcend the gym and serve youngsters well in a professional environment, whilst a majority stepping into squired circle will never win anything of note – they will all gain these intangible qualities that help them get ahead in life. Dr Prince, using his own life experience, explains how boxing turned his life around:

“It [boxing] wasn’t so much the destination of becoming a champ, but it changed my character. The process of going through training, understanding making good decisions – these are the things that you do in the ring. You have to be wise, you can’t let your emotions take over, you have to be professional, you have to be calm. I didn’t have these attributes before I started boxing.”

“When you look at successful people, whether it be athletes, boxers or whatever else, you will find that they have a certain temperament to them. There’s a certain character that they have – champions [mindset], when things get tough, they don’t get down. They use that to step up their game and become great through that situation. Through hardship they become great,”Prince told me, about how his time in boxing is still paying dividends daily.

The academic, Dr Jump, emphasises the role of a coach as a mentor is also important. She explains what she’s observed through her research into this issue, saying: “It is important that coaches not only teach kids to hit pads, but also how to be good sportsmen/women. This can be done by breaking down some of the barriers and masculine discourses inherent in boxing gyms.”

The lecturer adds that competent coaches can work wonders in breaking stereotypes of people from other backgrounds or young people from other postcodes: “If the coaches can break down barriers with ground rules, boundaries and teamwork, then young people can see the benefits of coming together with other young people like them. It is important to be encouraging, yet firm, and thus create positive spaces for young people to feel safe in. The worse thing, is when staff try and be ‘down with the kids’, and therefore collude in negative attitudes that can be conducive to crime.”

For an outside observer engaging young people in violent combat that potentially have gang affiliations could be a risky option. Perhaps the allure of the blood sport is what initially draws these young people from the streets, as the Box Up Crime founder, Stephen Addison, an advocate of boxing being a vehicle to help vulnerable and impressionable youngster in building character.

“When you are dealing with kids that don’t have confidence, that don’t have a lot of people investing in them, boxing is a great way to really engage with them. Now they are getting opportunities to get personal development, mentored and get motivated in an environment where people genuinely care,” Addison concludes.

The lessons learned beyond pad routines

Whilst the sweet sciences impact on young people is positive, despite being hard to measure, the Manchester Metropolitan University Criminologist, Dr Jump, argues that the next positive step for the sport is to have more female and a more diverse range of coaches to be present in gyms. She believes that this step can: “Send positive messages to young people about equality, and acceptance in sport, as well as teaching resilience and respect for others. Not surprisingly, this can have a positive impact on offending behaviour.”

Mark Prince believes gyms should look to incorporate mentoring in their coaching to help fighters prepare for a career in boxing or life outside of the ropes: “Mentor[ing] would be wonderful to be incorporated with fighters [training]. The fighters mind is very intricate, it’s very different to being an athlete in any other sport. What a great bonus if boxer could have mentors [as a part of training].”

The knife crime activist recognises the prominence of mental health issues in sports and with boxing being such a ‘macho’ sport sometimes fighters aren’t open to sharing their emotions. He believes that helping young people at an early age with mentoring and mindset coaching can lead to healthier lives in the long term. Furthermore, he is a proponent of financial literacy training for boxers – as he recognises that a career in the paid ranks can be short and only a few fighters remain in the sport after their career is over.

The reformed gang member, Addison, who founded the charity to help youths avoid a dangerous lifestyle, was awarded a British Empire Medal in last year’s New Year’s Honours. Most of the alumni of Box Up Crime don’t become household names of York Hall, but some have gone as far as turning pro, winning the ABA Championships and one of Stephen’s pupils boxed at the Commonwealth games.

The Londoner emphasises that despite many of his pupil don’t become professional fighters – they go onto become entrepreneurs, musicians and the skill and benefits from applying the skills learned in the gym in other areas in life. This in my mind is boxing’s ultimate gift to society.

The boxing industry can still do more to tackle youth crime

It’s encouraging to see many community leaders and social enterprises are taking proactive steps to help tackle juvenile delinquency. However, more could be done proactively by the wider boxing family to help address particularly knife crime and youth problems. Dr Mark Prince OBE’s charity, Kiyan Prince Foundation, has been tackling knife crime since his son was fatally stabbed back in 2006. The same can be said about Stephen Addison’s Box Up Crime, who champion tackling gang culture and youth violence.

The former World Light Heavy Title challenger’s public relations advisor, Melissa Takimoglu, who founded Melt PR eight years ago to help boxers to use their platforms effectively and to raise their profiles is leading the charge in making a rallying cry to the boxing industry to up its game in tackling youth crime. Her company has teamed up with the Kiyan Prince Foundation and Queens Park Rangers football club to launch ‘Inspiring Future Champions Campaign’ – designed to address the root causes of the violence and knife crime.

The initiative will deliver motivational speeches to over 20,000 young people across London in the next three years. This is in addition to out-of-school physical activities, which include boxing, and much more. The publicist has worked with the likes of Tyson Fury and Vasyl Lomachenko, Takimoglu, added:

“Inspiring Future Champions Campaign has been designed to encourage people in boxing, which includes promoters, managers, fighters, trainers or amateur boxers to get behind their fellow Champion, Mark Prince, and the new Inspire Future Champions programme. This is a call for action for the wider boxing industry to make meaningful strides to use their platforms and positions to get behind this amazing campaign.

“We are grateful for QPR (Queen’s Park Rangers F.C.) for leading the way by giving the naming rights of their stadium to the Kiyan Prince Foundation. But our work doesn’t stop there, and we need fighters and the wider boxing community to engage with young people, share their stories and ultimate help inspire the next generation.”

To find out more about this initiative please contact Melt PR on Twitter at @MeltPR.

Article by: Rikku Heikkilä

Follow Riku on Twitter at: @Lead_Right