Horror stories regarding poor boxing management of fighters are commonplace in our sport. The definition of bad or good managers is often varied and subjective. It’s become harder to outline what competent management and career advice looks like. Rather flippantly, us boxing fans are more than happy to label a fighter as poorly managed if an interesting match-up is being ‘marinated for too long’ or a lucrative purse for a potential fight is knocked back.

You can’t blame the boxing Twittersphere for their remarks, as the lines between promoters, boxing managers and advisors have become convoluted. Why shouldn’t fans or aspiring professional boxers assume that a charismatic person telling us what we want to hear is a good career handler? There’s certainly more to choosing a boxing manager than judging how well they perform down the barrel of a lens.

Novice professional boxers are unlikely to trawl through the reams of information on the British Boxing Board of Control (BBofC) website, familiarise themselves with board contracts or study managers and their track records. Perhaps to their own detriment – as many blue chip prospects are easily lured by cash advances and lofty promises in exchange for signing the dotted line on a complex legal contract, which appears too lucrative to turn down.

Reputable promoter and manager, Steve Goodwin, who has managed the likes of Dereck Chisora and Olympic champion Nicola Adams, warns fighters, “Somebody offering them something up front, they are going to get in the management fees”, adding that anything outside of the standard BBofC contract doesn’t often work in favour of the fighter, “We [at Goodwin Boxing] only have them sign the board contract. I’ve seen some of the other contracts that boxers have signed and I mean – oh my god!”

Universally people in boxing would say that trust, a solid track record and someone who is able to manoeuvre a fighter through the murky waters of the sport are the makings of a good manager. But in the Wild West of the business side of boxing, thirty-year veteran Dennis Hobson, says that it takes more than these attributes to make a good guardian for a boxer. “With Jamie McDonnell I know I did a lot of psyche [work] with him, and I definitely did with Clinton [Woods] as he was with me from the start until the finish [of his career]”.

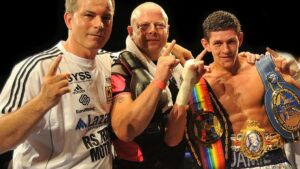

The Yorkshireman points out that sometimes a manager’s job is to truly understand the mental aspects that help maximise their fighter’s circumstances and thus, achieve peak performance. Hobson recounts the time he lured then undefeated Mexican, Julio Ceja, to Doncaster to face Jamie McDonnell for the vacant IBF bantamweight title.

On that night, McDonnell won by split decision, but he believes that if the fight was in Mexico it would of have gone the other way and it would have added a lot of unnecessary pressure on his pugilist. He learned this lesson the hard way, as his protégé and former IBF light-heavyweight champion, Woods, lost on the road to Antonio Tarver and Tavoris Cloud – two men that he believes that Clinton could have beaten on familiar soil, back in Sheffield.

A standard board management contract for a newly-turned professional fighter runs for three years, which is what most managers feel is a suffice instrument that protects both parties.

Lee Eaton, MTK Global’s promotional frontman, therefore emphasises that the onus is on boxers to find the right man to protect their interests, “You’ve got to do your own digging, you gotta realise that this is your career at the end of the day”, adding that the first offer isn’t always the best. “Look at their [manager’s] track record, you don’t just go with the first person, you’ve got to shop around really. [So] you know that you’re with the right person.”

London-based Steve Goodwin, was shocked when he started in the boxing business, as he couldn’t believe that some managers were taking up to 25% from fighter’s purses.

The gobsmacked manager has trouble comprehending how fighters at a lower level can make a living from boxing under these types of terms. His management company, Goodwin Boxing, operates under a different model and they don’t charge a management fee until a fighter achieves a minimum purse of £4,000, and even then the management fees is at 10%. Active small hall promoter, Goodwin, asks boxers, “You need to question, why they are taking 25% [of your earnings], what more are they going to do than we do?”

Dennis Hobson, the former manager of Ricky Hatton, said that it’s an increasingly uphill battle for managers to be the sole advisors for fighters. He questions the motivation of these hangers-on, who have the fighter’s ear – something that is on the up as entourages become increasingly common for boxers at all levels.

Offering a sobering perspective on how fighters sometimes turn their backs on the guardians that have been around them since the start, he explained, “When you’ve invested a lot of time and money in somebody, you do it for a return, but it doesn’t always come in boxing. It’s not like any other business – the time and money you invest it’s not very often that it comes back in dividend.”

These words of warning are echoed by MTK Global promoter, Lee Eaton, “There’s a lot of people in boxing who will sell you a load of lies, and you’ve got to look at what they’ve done for other fighters”, stating that fighters need to feel completely comfortable with the person in charge of their careers otherwise, “It’s a very very hard career if you pick the wrong person. I know many people that have picked the wrong person and their careers aren’t going anywhere.”

Ultimately boxing management is a long game, where managers often have to weigh-up instant riches against building something for the long term. A financial advisor by profession and one of the most active managers in Britain, Goodwin, opens up about why he enjoys boxing management, “The fun bit is manoeuvring fighters and seeing their career take off. That’s really what we aim to do.”

Hobson, who negotiated with the likes of the infamous Don King and evergreen Bob Arum, perceives that drawing up contracts gets easier to a degree at the highest echelons of boxing as there’s more parties involved in ensuring that legalities of the paperwork are watertight. Whilst at the grassroots level of boxing, solo managers are often tasked with overseeing more or less everything involved in putting together fights and promotional agreements.

This serves stark reminder that ‘good’ management is increasingly important in the early parts of fighter’s careers. Essex-based Eaton believes that a good manager and fighter partnership is a reciprocal agreement, “If you are a red hot prospect you need to look at what they can do for you, rather than what you can do for them. Because you need to make sure that they can do the job that needs doing.”

It’s easy to blame the powers that be for fighters getting bad deals – in this case it would be the BBofC. Goodwin, a man known for being candid, shines a light on the conundrum that the British governing body faces, “They try [to regulate contracts], but the thing about the board is that they only regulate one contract. The boxer’s manager’s contract. When the boxer signs another form [personal services agreement], the board don’t regulate it. The boxer has taken himself outside the boards regulations”, the manager affirms, “When you are signing another contract [on the side], trust me it’s not in the boxers favour. You shouldn’t need to sign one.”

As these three managers shed light on the business side of boxing, it’s clear that the onus is on the fighters to do their own research and look at a manager’s track record before appointing one. Unfortunately, in boxing, the cost of bad management can come at the expense of one’s career.

Article by: Riku Heikkilä

Follow Riku on Twitter at: @Lead_Right