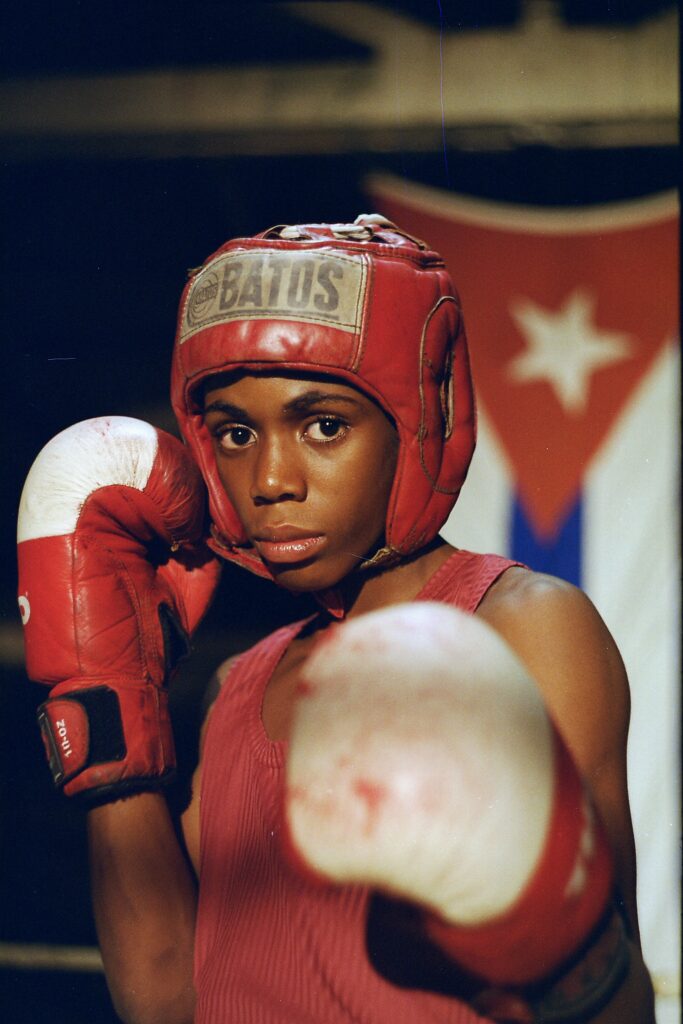

Tucked between deteriorating buildings, its chipped paintwork is splashed up and down the walls. Dusty, crooked seating sits empty, reserved for any loving, worried parents in attendance. The Rafael Trejo Gym in Old Havana, Cuba, is a far cry from the Island’s striking coastline, but it plays home to many of the country’s top amateur stars.

Fans of boxing may recognise the facility from Andrew Lang’s powerful documentary, ‘Sons of Cuba’ (2009). Lang tracked the success of three young Cuban amateurs, with a focus on the group’s prodigious talent, Cristhian Martinez, aged only 11 at the time of filming.

You probably haven’t heard about Cristhian since the film’s release – very few have.

Tracking down the national amateur champion over a decade later wasn’t easy. Cuba was rated fifth on the Freedom of the Net’s 2018 report, with its residents rarely able to operate social media accounts and prohibited from surfing the web freely. For reference, those countries rated with more severe restrictions to their internet included only China, Iran, Syria and Ethiopia.

‘What happened to Cristhian Martinez from Sons of Cuba?’ and ‘Sons of Cuba, where are they now?’ were two vague, hopeful Google crusades, with the latter leading to a forum post from a user in November 2017. After following the breadcrumbs, Cristhian was located – in Slovakia, of all places – via his Instagram handle ‘son_of_cuba’.

He had just turned 25, celebrating with his wife, who was a former Czech national amateur champion. They both knew all about the sacrifice required to emerge on the podium positions. And while somewhat disillusioned with boxing, Martinez spoke to Boxing Social about his decision to up sticks and travel to the other side of the world.

“It was very difficult for me to leave my family behind and to start from scratch,” Cristhian confessed. “I was living in Old Havana, and now I’m in a country where the language, climate and traditions hit you hard. Slovakia is a country where, for many people, it’s unusual to find a black person. It is evident. You sometimes feel that people don’t like you and I have found it difficult adapting to their society sometimes. I was never allowed to join the Slovak national team.

“I’ve been living here for almost four years now. A Slovakian coach offered me the chance to come here from Cuba legally and the chance to represent his club, and eventually the country at the Tokyo Olympics in 2020. I live in a beautiful city called Sabinov at the moment. The weather is a little colder than Havana, sure, but the people are very friendly here. I adore the city; it is the ideal place for a good training camp with its high mountains and for its clean air, but moving could also be good for me, in order to become a professional boxer.”

Martinez continued, “I don’t regret my decision to come to Europe. Yes, I’ve fallen a lot of times, but each one of those falls has allowed me to grow as a person and they have given me the opportunity to look at life differently. We Cubans are people deep-rooted in our own culture, but we can also live comfortably anywhere in the world.”

Cristhian’s move to Sabinov, a distance of almost 9,000km travelled in total, hasn’t led to the success he had originally imagined. He explained that, back in Cuba, he was frozen out of their amateur set-up, despite beating his peers in national competitions and consistently excelling in training. It didn’t make any sense to him, but when searching for Olympic recognition draped in the alternate vest of a foreign, Eastern nation, he still struggled to overcome prejudice.

in 2009 before disappearing off the wider boxing radar.

Photo: Andrew Lang/Sons of Cuba.

Boxing isn’t known for fairness. It’s known for rewarding the fighters with the highest profiles, and for giving its opportunities to promoters who are happy to continually line the pockets of governing bodies or licensing commissions. Martinez remembers wandering into the gym for the first time, blissfully unaware of boxing’s political afflictions and using the sport as his escape. That early education in the Rafael Trejo Gym in Old Havana was life-changing, for better or for worse.

“For my mother, studying was essential and she required good results from us. I remember that in my spare time I would sell plastic bottles, cardboard, iron and aluminium, without my mother knowing,” recalled Martinez. “I would pick up what I found on the street and then sell the items to a man who bought recyclable materials in our area. I just wanted to contribute, for her. Many times, I was in the trash trying to find things [to sell]. For that reason, she complained about the smell of my clothes, but I was only six years old.

“I was practicing boxing from a young age because my older brother also trained. One day my mother had to do her housework and I went to the gym where my brother trained. She left me there with the coach for only an hour and, when she came back, I was hitting the bag. Since then, I have never stopped training.

“How you feel on that first, official day of training at the gym is inexplicable,” he said. “I remember that there were many boys from my school, much older than me, and even other boys from my neighbourhood who were [training] in the gym. There were over 60 boys in our gymnasium and, after the first day of sparring, only 10 boys continued. In school it was forbidden to fight, so we took advantage of the gym. It allowed us to do what we loved.”

Andrew Lang candidly captured that love for boxing in 2009. Martinez’s relationship with his father Luis Felipe, the former Olympic bronze and world silver medallist (Montreal 1976 and Belgrade 1978 respectively), was central to the film’s plot. Both father and son wept as Cristhian won the Cuban national title, embracing and sharing their affinity for the most noble of sports.

Unfortunately, their relationship would drastically unravel, with Luis frequently working in Mexico and losing interest, or perhaps faith, in his son’s once-blossoming career.

Lang, the film’s director, originally met a young Martinez at an amateur show in Cuba. The boy was crying, unable to cope with a sickening defeat, and the British filmmaker would embark on the making of ‘Sons of Cuba’, focusing on Cristhian and his teammate, Santos Urguelles, as well as the academy’s head coach, Yhosvani Bonachea.

“I met Andrew when he was sitting in the audience with his camera and I had just lost a fight. I think that was the origin of his idea, filming a documentary on boxing at an early age in Cuba,” said Martinez. “‘Sons of Cuba’ was an incredible experience for us because it reflects the great sacrifice that children make when they are living away from their parents. They face that hard training to become champions. It was all real; very seldom did we know that the cameras were filming us.

“I lost my father’s support [after filming] and my career soon declined,” the aspiring, unsigned professional revealed. “My father stopped having time for me and I could never count on him at all. I never felt any pressure being his son, but many times I went to those competitions without any money, without the right equipment to compete, using only what my mother had managed to save. I was on the national senior team as a guest athlete, but then I had to serve in the Cuban military for 13 months.

“Many teammates and their parents kept me from being promoted to the Cuban national team again. It was hard for me to understand how I couldn’t participate in the World Youth Championships, because I should have qualified. But here I am, with more hope than ever, determined. There were many times I thought about abandoning boxing, but I feel like it is a part of me – it’s like an addiction.”

Photo: Andrew Lang/Sons of Cuba.

Lang told Boxing Social that Martinez is a “special man, who deserves all the success” in the world, with the pair remaining in contact since shooting. Just as the Cuban has continued throwing punches, Lang has marched on, winning multiple awards for his work behind the lens.

It seems unthinkable that any project since has gripped him as personally as ‘Sons of Cuba’, playing his own small part in boys like Cristhian’s childhood. The London-based director could frame their skills and sacrifice, showcasing them worldwide, but time inevitably moves on. Those young Cuban fighters often disappear from the amateur circuit after failing to make the cut for major, international tournaments. They carry on with life, acting as tiny cogs in the national, Communist machine.

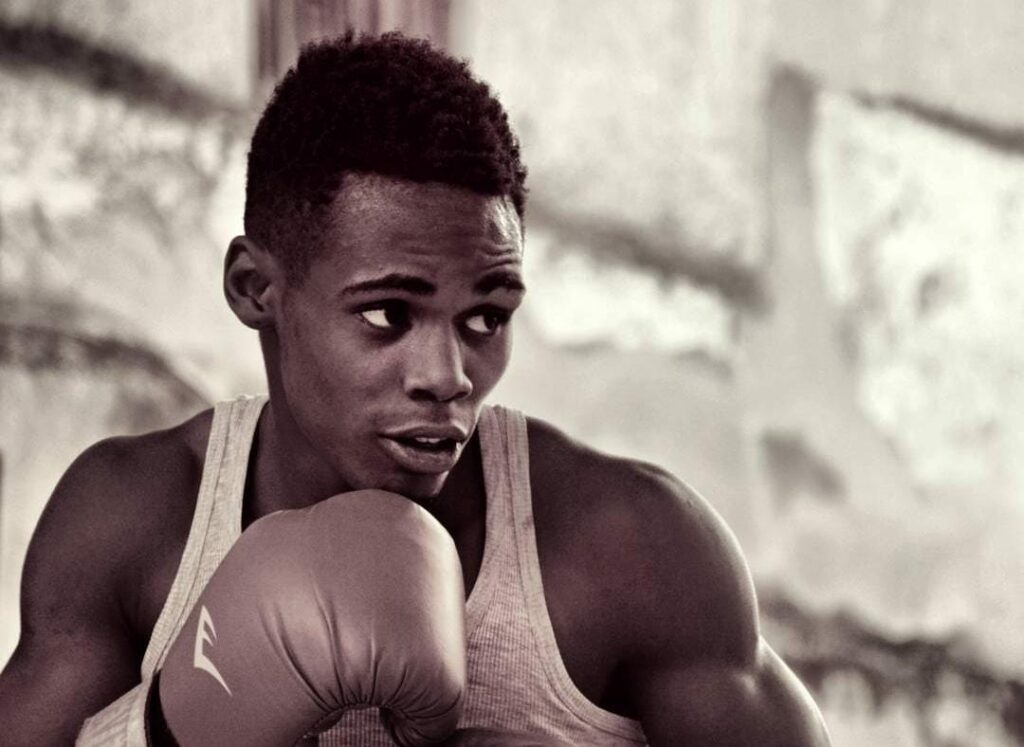

Alone in central Europe, Cristhian had initially hoped to follow his Olympic dream. But things never played out that way. He told Boxing Social of empty promises from the Slovakian amateur governing body and how he has represented his adopted nation only once in those four years, emerging victorious nonetheless. It seems that turning professional is his only option now and he spoke of recent invites to join a training camp in Spain.

setbacks. He is now focusing on a pro journey, possibly in Spain.

Photo: @son_of_cuba Instagram

Currently off the grid and living his own humble life in Sabinov, will boxing find Cristhian Martinez again?

“I think it would be impossible to predict when the time is right to become a professional boxer. Knowing that being an Olympian would have given me a better chance of being signed some good promoters, things just didn’t turn out as expected for me,” he said. “I have clear goals and becoming a professional is certainly one of them. I have a lot to improve upon, [a lot] to learn, adapt and transform in order to become an elite boxer. I must stop waiting for those doors to open for me as an amateur.

“It’s a concern that lives in each of us,” Cristhian concludes, with stark honesty. “You ask, ‘Will I make it or not?’ There is, of course, a slight chance that it won’t ever happen. But the key to success is to persist and never give up, staying positive. I didn’t have the opportunity to be in the youth or senior national team, but many of my teammates who were [in the team] no longer compete. They have given up. The sacrifices I make will serve me so well for the future. I am living in Europe thanks to those sacrifices for boxing. I’ll make it to the top and you will be there to see it, I’m 100% sure of that.”

The hard-working child, swimming in a sea of litter and searching for materials he could sell, probably never envisaged life like this. He was unable to follow in his father’s footsteps; he was frozen out of the Cuban amateur scene and suffered a similar fate in Slovakia. His devoted mother remains in Cuba – his biggest fan. She was captured on film attending his bouts back in 2007, filled with love and fear, and Martinez explains there isn’t a day that passes without feelings of loneliness in the absence of her support.

Maybe he will roll the dice and travel to Spain with the prospective, professional stable. Everything could still fall into place. There remains an innocence in Martinez’s eyes and warmth in his crooked smile. It seems more likely that ‘normal life’ shall reign supreme, as it does for most of us.

The star of one of boxing’s famed documentaries has been allowed to fade into its murky past. He genuinely believes his time will come. He’s travelled far enough for it.

from home, but with Cuba always in his heart.

Photo: Anna Grove Photography.

Main photo: Andrew Lang/Sons of Cuba.