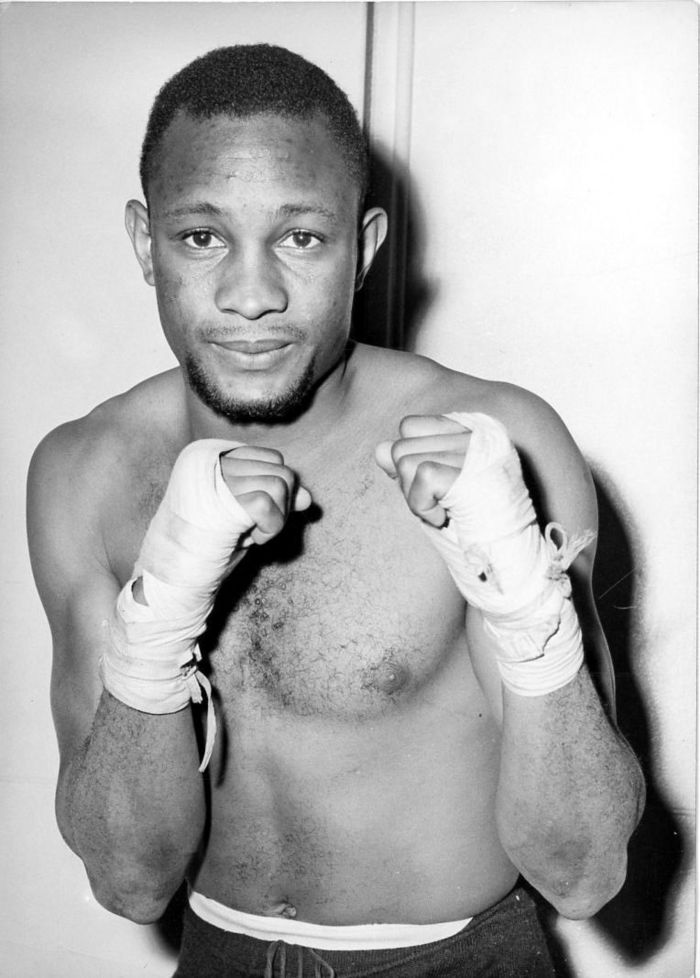

Curtis Cokes, who passed away on May 29 at the age of 82, was a beautiful stylist who perhaps never got the credit he deserved when an active boxer, even though he was undisputed world welterweight champion in the 1960s. He was deservedly inducted into the International Boxing Hall of Fame in 2003.

Cokes, the first world champion from the Texas city of Dallas, was overshadowed by Emile Griffith, who was considered the true welterweight champion when Cokes held the WBA version of the title. Unfortunately, Cokes is probably best remembered for his two defeats against the great Mexican-domiciled Cuban fighter, Jose Napoles.

Perhaps Cokes was under-appreciated because he wasn’t considered exciting. “Cokes never will any popularity polls with the fans,” reporter Lew Eskin noted in the January 1968 issue of Boxing Illustrated. “He is a throwback to the old school; he waits and waits and waits, looking for the opening… It isn’t until he has a man in trouble that he will become even in the least aggressive.”

In the same issue of the magazine, however, Cokes explained: “I know I am not a crowd-pleaser, but Cassius Clay said it right: ‘I don’t want to find out if I can take a punch.’ You get paid to fight, not to get hit.”

YouTube footage shows how good Cokes was. He had a relaxed, classy style and a superb left jab, while he hit hard with the left hook or right hand.

In his 1964 fight with local favourite Stanley ‘Kitten’ Hayward in Philadelphia, Cokes was winning the bout against a heavy hitter only to get caught and stopped in the fourth round. This bout was televised on the ABC network’s Friday Night Fights series in the US.

Hayward was a puncher who had a three and three-quarter pounds weight advantage and looked much the bigger man but Cokes scored a knockdown right at the end of the second round, outboxed his aggressive opponent in the third and, as commentator Don Dunphy noted, was “seemingly on his way to victory” when Hayward rocked him severely with a big right hand in the fourth. Cokes never recovered and was dropped three times before referee Zack Clayton waved the finish.

That contest was actually seen on British TV on a one-week delay when the BBC had a deal to show the American fight of the week series, which was a treat for boxing fans in the UK even though the bouts were shown in recorded form on the Saturday afternoon Grandstand sports anthology show. Cokes attributed inactivity to the Hayward KO defeat. He hadn’t boxed for a year and in fact twice temporarily retired due to difficulty in getting fights.

Cokes was a thinking fighter, a technician and sharpshooter, but he could produce dramatic finishes, as in welterweight title defences in Dallas against the South African southpaw Willie Ludick and Francois Pavilla, a capable French boxer who was born in Martinique.

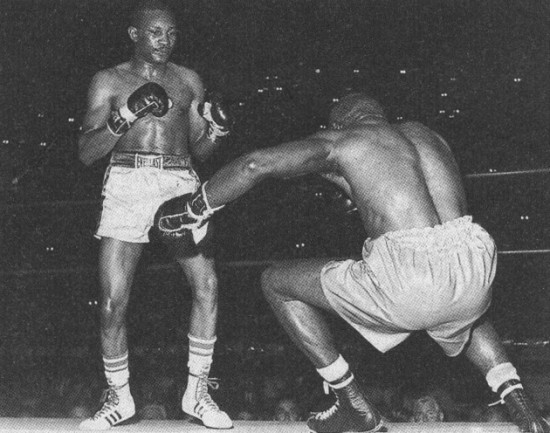

Ludick gamely took the fight to Cokes but was wrecked by three successive right hands in the fifth round. It was a breathtaking sequence — a right hand through the middle of Ludick’s guard, a devastating uppercut and then another right hand. But it was the uppercut that did the greatest damage. Although Ludick beat the count he was out on his feet and referee Lew Eskin allowed Cokes to land some more shots before the towel came in from the challenger’s corner.

The French challenger Pavilla had previously boxed a draw with Cokes in a non-title bout in Paris. In the title fight, Cokes sent Pavilla reeling back to the ropes with a left hook in the 10th round and the fight was as good as over. Pavilla went down but got up so quickly that it seemed the referee reacted too slowly to give him the mandatory eight count. Cokes quickly stepped in with a right uppercut and a chopping right hand to send Pavilla to his hands and knees.

This time Pavilla was given the eight count but it looked as if he didn’t know where he was and his corner tossed in the towel. (Referees in those days tended to let a fighter take more punishment than would be permitted today.)

Cokes, as was the way in his era, fought a string of world top 10 fighters. When the WBA launched a welterweight elimination series in 1966 Cokes stopped former champion Luis Rodriguez in the 15th and final round of a final eliminator. It was a rubber match, each having outpointed the other in 10-round bouts.

The Cuban Rodriguez got off to an excellent start, knocking Cokes down in the fifth round. However, Cokes came on strongly and by the 14th round Rodriguez was taking so much punishment that, according to a contemporary report, his trainer Angelo Dundee was close to pulling him out of the contest.

Rodriguez was allowed to come out for the 15th but immediately was in deep trouble, cut over the eye and bleeding from the mouth, whereupon Dundee jumped to his feet waving a white towel and urging the referee: “Stop it!” This the referee did after just one minute of the last round.

Cokes comfortably outpointed another old rival and fellow-Texan Manuel Gonzalez to win the vacant WBA title in August 1964. Cokes dominated the bout against a clever but cautious opponent, knocking down Gonzalez in the 12th round, which seems to have been the only real highlight in the 15 rounds. “Even the referee seemed bored,” Sports Illustrated reporter Mark Kram noted. It was Cokes’ fourth win over Gonzalez in five meetings.

When Emile Griffith moved up to middleweight, Cokes added the vacant WBC title to his WBA championship on November 28, 1966, by winning a unanimous 15-round decision over Jean Josselin, France’s European champion who seven months earlier had hammered Wales’ Brian Curvis to defeat in 13 rounds in Paris. Josselin was a strong, pressure-fighter type but Cokes was too skilled.

“In winning, Cokes showed nothing new; he won because he was the better equipped fighter,” Lew Eskin reported. “He made excellent use of his 12-inch reach advantage to pile up the margin of victory behind a stiff left jab.” Josselin bled freely from the nose, and in the last round the French boxer suffered a severe cut over the eye. “If this cut had been opened in an earlier round it is doubtful that Josselin would have been able to last out the fight,” Eskin noted.

In those days there were just two major sanctioning bodies. Cokes made three successful defences of the combined WBA and WBC titles, all stoppage victories. In addition to the wins over Ludick and Pavilla, Cokes stopped local fighter Charley Shipes in the eighth round at Oakland, California in October 1967. An excellent boxer, Shipes was unbeaten in more than four years and was recognised as champion by the California commission, but Cokes knocked him down four times.

Cokes, as was the norm in his day, boxed in a number of 10-round non-title bouts. He suffered just one loss in a four-year span, when the flashy, unorthodox Gypsy Joe Harris outpointed him in a non-title fight at Madison Square Garden. But Jose Napoles was just too fast, skilled and powerful, with Cokes suffering badly swollen eyes before his corner retired him after 13 rounds at the Inglewood Forum in Los Angeles. In a rematch in Mexico City, there was a similar ending, this time with Cokes’ corner calling it a day after 10 rounds, in June 1969.

Although Cokes boxed on for another three years, including a series of middleweight fights in South Africa (won two, lost one), he was never the same fighter after the two defeats by Napoles. He left boxing with a record of 62-14-4 (30 KOs).

After retiring, Cokes became a respected boxing trainer. I chatted with him backstage at the Emerald Queen casino in Tacoma, Washington, in March 1999. That night, Cokes was in the corner with heavyweight Ike Ibeabuchi (who stopped Chris Byrd in the fifth round). Neither of us could have realised that this was to be the troubled Ibeabuchi’s last fight.

A low-key individual, Cokes never had anything negative to say about any of his opponents. Reporter Mark Kram once described Cokes as a “laconic, inconspicuous gentleman”, and this wasn’t far wrong. Cokes wasn’t the type of man who felt he had to do a lot of big talking. He let his talent speak for itself, which it did, many times. It was a privilege to have known him, however briefly.

Main image: Tom Shaw, Dallas Morning News.