“Every single day that goes by I am more and more proud of it. When people look through the history books, my name is going to be there.”

This was how Duke McKenzie described being a three-weight world champion, something that has only been achieved by two other British boxers, Bob Fitzsimmons and Ricky Burns. Carl Frampton will be looking to join them when he takes on Jamel Herring for the American’s WBO super-featherweight title next month.

It would be fair to say that McKenzie did not harbour professional world title ambitions during his amateur days. In fact, he believes he has the worst amateur record of any world champion in the history of boxing. Quite contrasting to Frampton who lost just 11 of his 125 amateur bouts.

“My amateur record was 65 fights, 28 wins. For a world champion boxer to have a losing amateur record is quite something. I did not win an ABA championship and I never wore an England vest. However, while I never performed brilliantly, I did have the opportunity to train with some great boxers, not least my brothers. I was always learning.”

While Frampton had promoters chasing after his signature when he turned pro in 2009, the result of McKenzie’s amateur career was that he was not a particularly sought-after acquisition for managers or promotors. He had to take matters into his own hands.

Early morning phone calls to Mickey Duff at all hours of the day, unannounced appearances at his office in the West End, even making tea for his staff, were all part of his ploy to get signed by his management. “I was 19, unemployed and behaving like a lap dog, I became an errand boy. For months he politely asked me to go away but by the end I broke his resistance. Those 6am phone calls and getting on my hands and knees paid off in the end,” recalled McKenzie.

Once McKenzie started out on his pro journey, directed by Duff, he was not setting his sights too high.

“All I wanted to do when I set out was bank a few quid. I was unemployed after all,” he said. “However, things took off quite quickly after having numerous low-key fights in America. During this time, I was training amongst legends like Evander Holyfield. It made me really believe in myself and, before I knew it, I was 9-0. The next fight was for a British title and I was well on my way.

“Not for one second did I believe I was world class, but I had become world ranked. I started to look at my resume and saw the fighters I had beaten and started to become more confident. In the blink of an eye, I was flyweight world champion.”

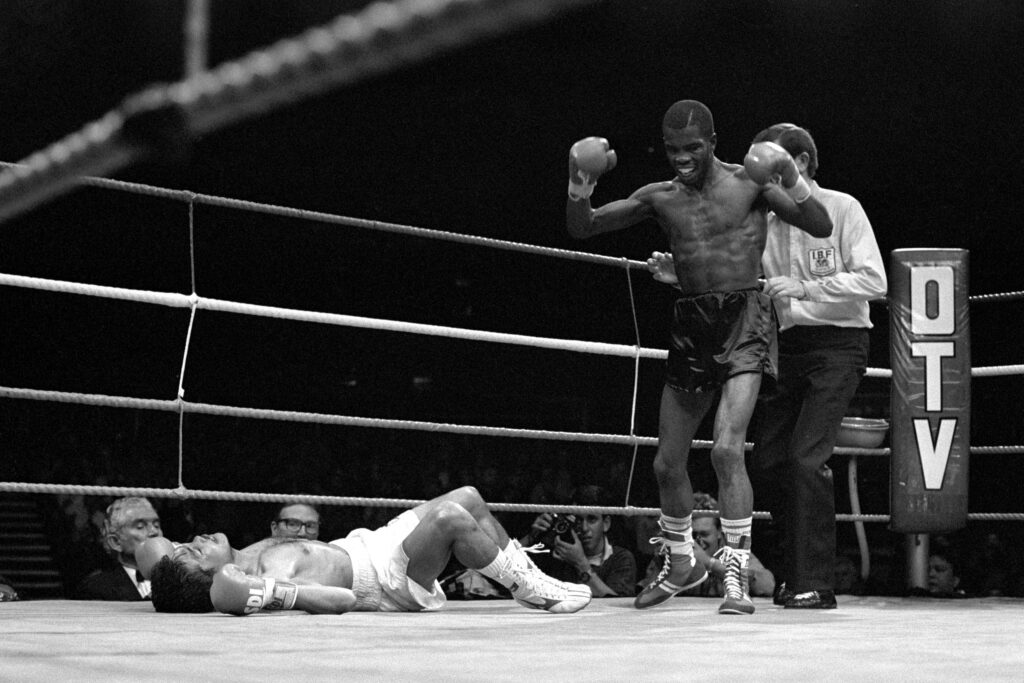

October 1988, his first world title. Photo: David Giles/PA Archive/PA Images.

Despite world honours, McKenzie strongly believes he was still a work in progress. It was not until he fought for a European title at bantamweight that he really became rounded as a boxer.

“The most I learned was fighting and losing that bout. It was against Thierry Jacob and was the fight of my life. I’d never experienced hostility, I’d never been decked, I’d never been in a fight where I felt like crying, there were so many twists, turns and plots. My world title fights were nowhere near as hard as that night.

“I learnt more in that fight than in my previous 24. Jacob won the world title in his next fight against Daniel Zaragoza. It was then that I finally realised I was world class, despite already being a flyweight world champion. He set the blueprint in terms of what I needed to do if I wanted to challenge for another world title.”

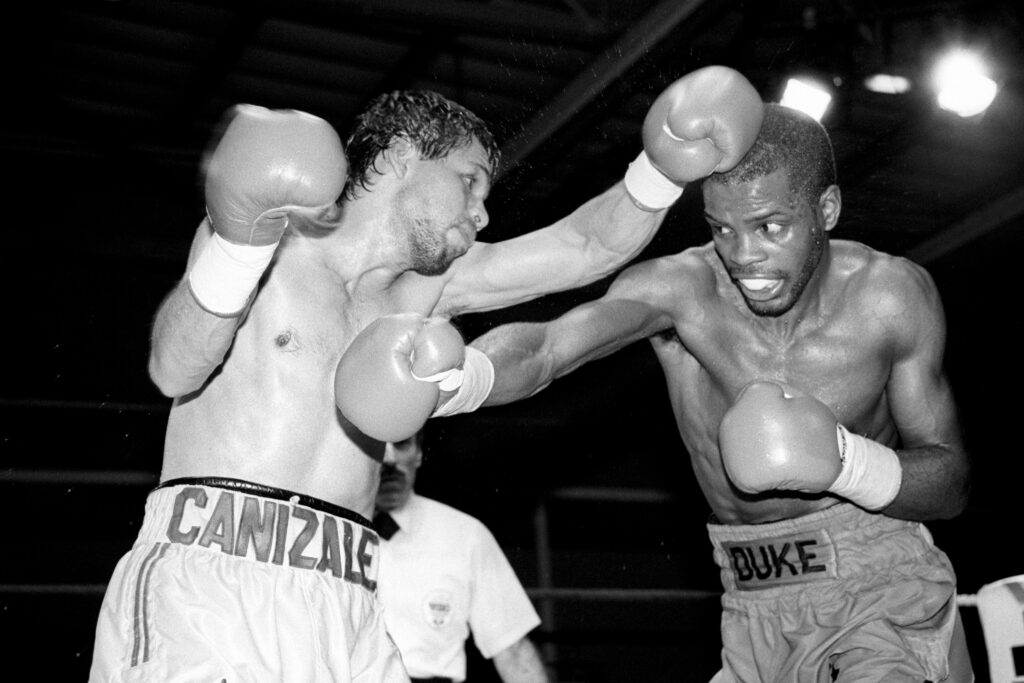

From this fight, McKenzie increased the intensity of his training regime. “I had to learn different skills, particularly how to suck it up and dig in. The tactics he used to beat me I used to beat Gaby Canizales at bantamweight and Jesse Benavides at super-bantamweight. I have a lot to be grateful for regarding the fight. It is quite simply why I became a three-weight world champion.”

Gaby Canizales in June 1991. Photo: Sport and General/S&G and Barratts/EMPICS Sport.

McKenzie does not believe that Frampton will be overawed by the magnitude of what he is trying to achieve in a few weeks, believing his sole focus will be on the man at the other side of the ring, and that was certainly the case for McKenzie when he beat Benavides to achieve the feat in October 1992.

“Lots is made of champions in terms of stature and status. I could not afford to get caught up in it. Before I fought Benavides, he was Ring magazine ‘fighter of the month’, had only ever lost once in 36 fights and was on a roll. My sole focus was on Benavides and what I had to do to beat him. I always had a feeling he had taken me lightly. Deciding to come over here on a cold October evening as champion, it struck me as a strange decision. I am convinced he looked past me.”

The task that lay in front of Frampton is somewhat different to that of what McKenzie had to overcome in 1992.

“I was actually taller than Benavides. By the time I moved up to my third weight division everything had fallen into place, power, speed, technique. This was me at the perfect weight. In my opinion, Frampton reached this level at featherweight. Whether he can bridge that gap against a man that is a massive super-featherweight is a real doubt in my mind. Frampton is five inches shorter than Herring. He also hasn’t won a world title fight for four-and-a-half years; he could be a bit long in the tooth.”

McKenzie knows how it feels to jump up too many weight divisions when you are passed your best, being knocked out when attempting to win a world title at a fourth weight division against Steve Robinson in October 1994.

“The difference is ridiculous. It was like hitting a brick wall. I hit that guy with my best shots and they just bounced off him. On top of that, their punches really sap your energy. You cannot wrestle the guys who are naturally so much bigger than you. I didn’t hurt him once,” said the three-weight champion.

“I hit him with a good clean head butt and I hit him low once or twice, that hurt. But when I hit him with a head shot, he never grimaced, he never moved back. It makes you question yourself; you lose heart, your mind goes and then you get caught with more shots. I simply was not a fully-fledged featherweight and Carl is not a fully-fledged super-featherweight.”

With all of this in mind, McKenzie feels there are more questions than answers when it comes to Frampton winning this fight.

“Herring is nothing special, it is not like he is fighting a [Leo] Santa Cruz or an all-time great. Frampton will not have a better opportunity, but I do have my reservations,” said McKenzie.

“There is the hope that Herring may have taken Frampton too lightly. That is certainly what Benavides did with me. If that is the case, this could be a big night for Frampton. The big advantage is that he is fighting the kid over here, albeit behind closed doors. It would be better if it was in Ireland full of fans that can lift him that extra 20%.

“But the longer the fight goes on, you really have to fancy the champion. He is bigger, stronger and pretty savvy. Most of the advantages are with Herring. That said, he is not a massive puncher and has never beaten anyone of the calibre that Frampton has.”

One thing is for sure, McKenzie is in absolutely no doubt who he wants to win the fight.

“One million percent I hope Frampton wins. I like the kid and have followed his career closely. I covered his pro debut on TV. He is a tremendous fighter that knows he is in the twilight of his career. It is whether he has one more big fight in him,” he said.

“To be one of four fighters to achieved three-weight status in this part of the world, the achievement speaks for itself. I hope Frampton’s name can sit alongside mine, I really do.

“It would be great to have an Englishman, Irishman and Scotsman to have won world titles in three weight divisions, I am sure there is a joke in there somewhere.”

What is no joke is the challenge that lies in front of ‘The Jackal’ on February 27. Here’s hoping the technically gifted man from Belfast can join Fitzsimmons, McKenzie and Burns in that exclusive club.

Main image: A jubilant McKenzie celebrates victory over Jesse Benavides to become a three-weight world champion in October 1992. Photo: Sean Dempsey/PA Archive/PA Images.