The cruel winter wind slices the faces of those meandering from pillar-to-post, hunting for their purpose on the streets of New Jersey. The young men, with hands deep in their pockets in areas such as Pemberton or Hillside Township, are searching for their own means of escape – though, fast money always seems to render them helpless. Glued to the sidewalk.

Over one hundred years ago, ‘Jersey’ Joe Walcott was introduced to the world in Pennsauken, a small settlement which, at the time, only boasted 5,000 residents. Boxing was big in New Jersey. It always had been. The startling differences between Walcott and the man on the other end of the phone, were the opportunities presented to the former at the elite level.

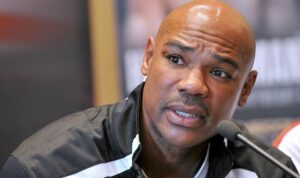

“Just imagine; giving something your all, going through a divorce because you’re dedicating too much time to boxing. Being away from your kids, having no friends, not doing anything with your family – all because you’re focused on boxing.”, ranted the passionate, yet deflated Amir Mansour (23-3-1, 16 KO’s).

“…Then, you don’t fight for a whole freakin’ year. After the [Travis] Kauffman fight, the winner was supposed to get [Deontay] Wilder. We fought for the WBC US title, now mind you, after winning that fight, it was my sixth or seventh junior title. I was thinking, ‘Okay, I finally get in-front of Wilder’, but then I don’t fight [at all] for a year!”

Mansour was rightly agitated at the state of boxing, not just for himself, but for many others sitting by the phone. He proclaimed he wasn’t the ‘only Amir Mansour’, deserving of his title shot and left out in the cold, as he had been many times before. The forty-six-year-old contender, however, had a story much deeper than the inner-workings of a contentious sport.

The product of an impeccable family, Amir explained the temptation faced by young, black males – often scrutinised for becoming victims of their own illicit environment. His mother was described to me as an angel, taking her son fishing and supporting his blossoming interest in various sports such as baseball and [American] football. Yet, despite being surrounded by love, the whisper of the street grew louder.

“What kept getting me in trouble? Just not giving a fuck. Just not… giving a fuck. I mean, I had a beautiful childhood. Now, my environment, man… It was like literally you could go outside with $20 and if you hustled right, you could end up with $2,000 the next day. Literally. That’s what got me, the fast cash.”

He continued, “That fast money really got me and it took a long time for me to get out of that mentality. When I was seventeen, I got into some trouble and I went to jail, but because of the trouble I got into they weighed me up and sentenced me as an adult – sent me to an adult’s prison. In New Jersey, they had boxing in every single prison. They would have an annual tournament and the jails would visit each jail, except Trenton and Rahway, they couldn’t travel. The other prisons would travel to Trenton and to Rahway for this annual tournament and you would be the prison State champ.

“I started boxing in prison and they used to call me ‘Young Un’, cos I was the youngest guy on the team as a juvenile in the adult facility. These guys would send me back every day with a bloody nose and I just got better. Each guy that used to whoop my ass, I ended up knocking each one of em’ out.”

‘Hardcore’ was incarcerated for his final spell at the age of twenty-eight, but after amassing a record of 9-0 (6 KO’s). His time in prison doing that stretch in particular, was by far his longest and most meaningful. The changes made upon his release were permanent, forging a career as a top-level heavyweight and challenging fighters in-and-around the top-ten of many governing bodies. Beating the relatively highly-touted Travis Kauffman, finishing level with Russian Sergey Kuzmin and having a ‘draw’, dubiously, with Gerald Washington had been his biggest achievements at the top level, thus far.

“I knew that I could become World champion. I started believing in myself after that eight-and-a-half year prison sentence. We trained in a little closet, doing shit you would get thrown in the hole for, they just allowed us to do it. They saw the dedication that I had and I knew that I could be a great fighter. I just never, ever considered that I would be ‘too good for my own good’. I always thought that if I won enough fights, I would get a World title shot. That is just too far from the truth, man.”

This was the premise that had broken Mansour’s will. Repeatedly told by fans and people involved in the fight game that he was ‘too good for his own good’, and therefore being avoided by the champions, seemed sickening to a man who relied solely upon his morals and his word. The best fight the best. That should be how champions are moulded, he told me, almost in disbelief.

His last outing had been a stoppage loss to Croatian prospect, Filip Hrgovic, in the Summer of this year. Before eventually stepping into the ring, Amir had been scheduled to fight no fewer than five times, let down mid-camp to the tune of thousands of dollars. Providing for his family was his priority, though taking fights to progress his career came a close second. Saddled with uncertainty, he had taken the fight on the Sauerland show for all the wrong reasons.

“I was just so frustrated and literally stressed the fuck out. We have families to take care of, man, you know? I’m training to fight, then the fight’s off. Running through money and camps and we’re not receiving any back, so when they called us for that fight, I had stopped training [already]. I knew I wasn’t there mentally. I was so frustrated with the sport. Period.”

“After the Filip fight, I didn’t know I would be as disappointed as I was.”, he confessed. “Going into the fight, as I said, I wasn’t ready and I took it cos I knew I had to pay some fuckin’ bills. I thought I’d be okay with that… But I’m not and I’m very disappointed in myself. I feel like I shouldn’t have trusted the industry. I feel like I shouldn’t have put so much faith in the process.”

After experiencing his own political disappointments with boxing, Mansour was aware that life at the top of the tree was difficult. Fighters possessing secondary belts, mandatory positions or lofty rankings were realising that there was no ‘next-in-line’. The sport had evolved, even since the nineties where fighters such as Lennox Lewis, Evander Holyfield, Mike Tyson and Riddick Bowe would battle for supremacy.

Although reaching the end of his own career and balancing the straws that threatened to break his back, Amir demonstrated an understanding of the industry. The lack of super-fights and the isolation of boxing’s ‘stars’ had meant certain promoters could control contests and championships. The heavyweight World title, he explained, was synonymous with sport – as was the Super Bowl or the World Series.

“Inflation exists everywhere in the World except for boxing. Look at the money Mike Tyson was making twenty years ago. Now, look at the money that Joshua and Wilder is making today. Wilder is lucky if he gets $3mill for the bums he is fighting. I don’t know Joshua’s situation, but I know he’s not making the money that heavyweight champions were making twenty years ago! Now it’s about being the champ and picking the weakest link. This is why the heavyweight division is dwindling, you gotta think! If inflation existed in the heavyweight division… If they were making $25-30mill to fight each other twenty years ago, how much should they be making now!?”

The New Jersey native confessed he didn’t know if he’d ever fight again. Probably. Being fed stories of potential opponents and fictional dates had worn thin for a man who had to earn. Locking himself in the gym, staring at the walls through eyes glazed in sweat, sacrificing time with his children in pursuit of a dream that seemed… too far from the truth.

The New Jersey native confessed he didn’t know if he’d ever fight again. Probably. Being fed stories of potential opponents and fictional dates had worn thin for a man who had to earn. Locking himself in the gym, staring at the walls through eyes glazed in sweat, sacrificing time with his children in pursuit of a dream that seemed… too far from the truth.

It may have come too late, for Amir. Naturally talented, nurtured in the toughest of surroundings, his journey had been a success, even if he hadn’t initially viewed it that way. It was clear that his passion for boxing remained, though the reality of its shortcomings echoed in his voice. I hoped we’d see him have one last attempt at fulfilling his dream, which had become his escape from the lure of the icy streets and hardened cell-blocks he frequented as one of New Jersey’s statistics.

“They told me I was gonna fight Wilder on January 6th, I was so happy. I was crying, man. I’m literally crying in the gym when they called me. My dream has come true, I have accomplished the impossible… It was too much. I thought I would beat Wilder and make my money when I was the champ! Wilder heard that I had accepted and he said, ‘Nah, I’m gonna fight Szpilka!’“

“I don’t even fucking care about winning anymore. I can’t afford to stay in the gym anymore because boxing isn’t paying me! I gotta go and make an earning for my family, but you wanna call me a week or two before the fight? There’s plenty of guys like me, too. I see guys in some top positions who haven’t got nearly as much talent as me, running about in Lamborghinis and shit.”

“Of course I’ll fight again, but nobody in the world can escape father time. I’m forty-six. I think I’m a freak of nature, I’m serious! I was in the gym sparring with a younger heavyweight and I was much faster than him. I surprise myself! I know I’m still good enough and if somebody calls and they want a fight, I’ll take the fight depending on what they’re paying…”

Article by: Craig Scott

Follow Craig on Twitter at: @craigscott209