“What am I going to fight for? Unless someone comes over and says, ‘Andy we’re giving you four million dollars.’ Or stupid money that you could say, ‘Well, look it’s worth it.’ But otherwise you’re just chasing something that’s not really there anymore. I’m happy now. It’s just fulfilment,” explained fighting favourite and now professional trainer-manager, Andy Lee(35-3, 24KOs), when speaking to Boxing Social from the comfort of his family home.

“I’ve won my world title. I’m not a multi-millionaire, but I did enough – I did all right to set myself up financially. And what else is there to do like? I’m 35 now, what was I then at the time, when I retired, 33? Still young enough to fight, but only getting older. Younger, stronger, hungrier fighters are coming up. What’s there to hang around for? You might want to have a fight, you might want to chase something, but you’d always regret it if you got beat by somebody who, at your best, would never have laid a glove on you.”

Lee’s exceptional description of retirement caught me off-guard early, sneaking in behind a lazy defence, as he’d done so often throughout his fruitful career. He was relaxed, despite being in lockdown with his wife, daughter and unborn, second child. The downtime he’s enjoying now has been forced through the Coronavirus pandemic, but after months of hard work in his own gym, with his own stable, and after basing himself Stateside for an exceptional heavyweight clash, it was welcomed. Itchy hands are less dangerous when holding pads and plotting the route to victory from outside of the ropes.

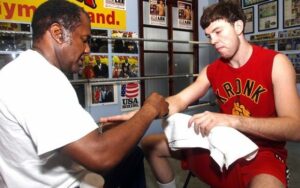

We spoke midweek and I caught Andy on an afternoon painted with nothing but empty sky. He was due to fly out to New York that weekend with young prodigy, Paddy Donovan, set to fight professionally for only the fourth time. Their trip was cancelled and Lee’s gym was closed. It seemed a good time to discuss the transition from fighter to professional coach, which hadn’t always been a part of his plan post-boxing, though his work with the legendary Emanuel Steward and highly-revered, British trainer Adam Booth has provided an impeccable grounding.

Based just outside of London, Booth and Lee worked together after Steward passed away, forging an interesting bond between two of boxing’s deeper thinkers, creating their own blueprint. But it was in Detroit that the young Irish kid became a man under the tutelage of one of the sport’s greatest ever influencers. Steward became like a father to his fighters, thriving in the face of adversity. Far away from home and training with monsters at the Kronk Gym, Lee has taken that experience and now looks to shape his own fighters using the power of psychology, coupled with good, old-fashioned work ethic.

“My training style and my philosophy would be from Emanuel’s side, but in terms of the technique and the things that I teach, a lot more now I think is from Adam Booth, in terms of what I learned from him later on in my career. It really was the making of me because I had that Kronk background, so I could always box. I always had that emphasis on the job at hand, which was a Kronk thing, but I needed to add things and Adam added those. Whatever Adam’s influence, everything happens in life for a reason and you end up where you are, but really all those people along the way played their part, you know?

“My training style and my philosophy would be from Emanuel’s side, but in terms of the technique and the things that I teach, a lot more now I think is from Adam Booth, in terms of what I learned from him later on in my career. It really was the making of me because I had that Kronk background, so I could always box. I always had that emphasis on the job at hand, which was a Kronk thing, but I needed to add things and Adam added those. Whatever Adam’s influence, everything happens in life for a reason and you end up where you are, but really all those people along the way played their part, you know?

“I think a lot of it is psychology and knowing what motivates the fighters, and knowing how to inspire them and let them know what’s expected of them,” explained the former WBO World middleweight champion.

“I think that was Emanuel’s strong point. Obviously he was on the pads and his philosophy of boxing was strong in every aspect, but there was technique, teaching and training of fighters. Also as a corner man, guiding you through the fight, sensing your opponent and reading your opponent during the fight, telling you when to put the foot down or when to ease off and try to box conservatively, he was just a master.

“When he spoke to you, how he groomed you, what the mindset was and how he’s had to impart his philosophy upon his fighters and the confidence he’d give his fighters, like… It was a huge part of his game. It’s hard to know, because he was such an influence on my entire life, how much of it you do absorb, but I try to [absorb it all]. I was thinking every day, ‘What would Emanuel do now? What would Emanuel do in this situation, how would he handle this? How would he handle that?’ His presence was felt during that [Tyson Fury] camp, because I was always reminding myself about him and what we used to do.”

That tuition, paid for with blood and faith, had led Andy Lee to the pinnacle of the sport as a fighter. But in taking the chance to move overseas, he’d also separated himself from those fighters content to sell tickets to a small legion of fans, never really improving and constantly competing on a smaller circuit. I asked if he found the move to Detroit overwhelming, as Northern Irishman Wayne McCullough had when moving to the US to train with Eddie Futch. ‘Not at all,’ he replied, without hesitation.

It was a tough education and certain aspects of the sport were hard-learned. Lee told me that nowadays, boxing houses less crooks, dressed in suits shaking hands with fists full of fake promises. Back when he was fighting it was rife, with cowards squeezing every last cent from the men trading blows. He was thankful for his time in the States, but I got the impression without his trusted, experienced team, this story could have suffered a different conclusion – like so many others. Stepping away from home comforts in either London or back in Ireland had forced the Body Puncher to pour everything into boxing. He was alone, but regrets were saved only for retirement.

“It was a dream come true. It was the chance of a lifetime, being from rural Ireland, Castleconnell in County Limerick, and being asked to go to Detroit and then to be training in the Kronk gym with Emanuel Steward. You’re not going to get those chances again, so even though it took time for it to materialise, I knew it was the right thing to do. It was the right chance to take. I don’t know, I hear about young fighters now saying they miss being away from home and camp is hard and all this and that. I absolutely loved it!

“I was in Detroit, but I was rubbing shoulders on a daily basis with guys who I’d only grew up reading about or watching on video. So, obviously there were days when you missed home, but that wasn’t an overriding thing. I was living my dream, really. So it was an unbelievable experience and straight away I was in camp with Jermain Taylor, training regularly. You’re travelling all over the world with Emanuel and for all of the HBO fights, I was ringside while he was commentating. I’d be meeting the guys who would have been at the top at that time; Barrera, Pacquiao, Hopkins, De La Hoya, Roy Jones Jr. – he was my favourite fighter. Those type of things, as a young man, I was living my dream, you know?”

Those nights under the bright lights of cities like Brooklyn, Esbjerg, Gelsenkirchen, Manchester and of course, Las Vegas, have given Andy memories to last a lifetime. Lifting the World title after stopping former amateur star Matvey Korobov in destructive fashion in Sin City had been his highlight, subsequently fighting to a split-decision draw with Peter Quillin in his first defence, and then losing to reigning WBO World super-middleweight champion, Billy-Joe Saunders. But everything had started to catch up with the Limerick-man by that point, with injuries testing his patience.

He fought Saunders with a detached retina, determined to fulfil his obligation as champion and avoid his loyal fanbase having to cancel flights or hotel bookings for a fourth time. Andy told me he visited his GP and within 20 minutes, was having surgery at a hospital in order to repair the damage to his eye. He laughed as he pondered whether things would have been different, admitting at that stage of a long, hardened career, that he felt burnt out by the whole process. The 35-year old would fight only once more, beating American gatekeeper, KeAndrae Leatherwood in Madison Square Garden. His eleven-year tenure as a professional was over, winning on points after eight, uneventful rounds.

“I kind of just… had enough. Not that the fight had gone out of me, but I knew that there were other things in life that were taking priority. Boxing was becoming less and less of the main focus of my life. From that year in between the Saunders fight and the Leatherwood fight, I got to do the things that I could never do, because I was always training or preparing for a fight. Or never knowing when the next fight’s coming, so you have to stay ready. Things like going to the pub and going on a few holidays and things like that. I got away from it a little bit, and then the hunger goes out of you and obviously when something leaves you, something else fills the gap, and my daughter was it. I didn’t miss boxing.”

Thankfully, boxing hasn’t had to miss Andy Lee. His reinvention as one of the sport’s most popular commentators and analysts has been seamless, but it’s a passion for paying forward the teachings of greats like Steward and Adam Booth that has seen Lee come into his own in recent months. His small stable – minimalist by choice – continue making strides, with anyone present in their gym left awestruck by the dazzling ability of Paddy Donovan.

However, it was Andy’s work with World-ranked Jason Quigley, an exceptional amateur, that I found most interesting. In Quigley, he has a fighter who’d attempted to emulate his success by rolling the dice and moving to Hollywood, only to return after suffering through boxing’s crippling isolation. I got the impression that psychology would play a crucial part in their race towards titles. Lee’s calm, concise delivery was exactly what Jay needed, and it was difficult to find fault when he spoke freely about boxing.

Working with his own two lads has given him a sense of immense pride and purpose, but one of Lee’s greatest nights in boxing came as a second in the corner of WBC World heavyweight champion, Tyson Fury, less than two months ago. Fury had approached his second cousin after deciding to amicably split from Ben Davison, and all roads led the pair back to the Kronk, where Tyson had visited Detroit-resident, Andy Lee, years earlier. The retired, former champion introduced the enigmatic Fury to Emanuel Steward’s nephew, Sugar Hill, and the trio almost immediately got to work.

After the Morecambe-man destroyed defending champion, Deontay Wilder on American soil in February, journalist Declan Taylor shared a story about an experience with Andy at the airport. As both men enjoyed a drink post-fight, debriefing an incredible night from ringside, they were approached by an American passer-by. Lee’s feet had barely left the canvas after celebrating an unthinkable victory with Tyson and their team in the ring, but the pair laughed as they waited for their flights home the following afternoon.

“We were having a couple of drinks and just reflecting on it and some guy was like, ‘Oh, so did you guys see the fight, what do you think?’ And I say, ‘Oh yeah, I caught a bit of it, you know.’ Declan just started laughing. It was just one of the best nights I’ve experienced in boxing, even compared to my own career because, because I felt so much pressure and so much weight [on my shoulders]. Obviously, I’m very close to Tyson and he’s a guy I care a lot about, I want him to win the fight as much as I would want to win the fight. But the fact that he called me up and put his trust in me to recommend a trainer, and the fact that he asked me to be involved as well. We were the ones who wanted him to fight this way. We were dedicated to it. All day, every day, all we practiced what was you saw, nothing else.”

Andy continued, detailing his relationship with the enigmatic Gypsy King, “I didn’t know Tyson. When I turned pro, after a while I started to hear about him, but I didn’t really know him growing up because he lived in England and we were second cousins. He wanted to box for the Irish title and he was trying to trace his Irish roots, so he got in touch with my dad who would be his mother’s first cousin. And my dad went and had to sign an affidavit because he had no birth papers back in Ireland to say that his granny was my grandmother’s sister. She was born in Bansha, County Tipperary, so that’s when we first really go to know him.”

“He came to a few of my fights in Dublin, and I went to his fights in Dublin and then in England, and we didn’t really get to know each other properly until he came to Detroit with me that time, and that was it. We hit it off. He’s always admired me for going to America and fighting in the Kronk, the fights I had and the fights I won. I’ve always admired him because I know the talent he has. I don’t think he knows how good he is. And he’s quite self-deprecating. He’s quite modest, but he’s unbelievably talented and I don’t think he realises how good he is, because men his size shouldn’t fight like that. Men his size can’t fight like that in terms of being that coordinated and being able to do all the things he does. Also to have that will and the strength of character that we’ve all seen now, that’s what people don’t realise: he’s bred to do this. If you look at his family history they’re all fighting people.”

Bred as fighting men, both Lee and Fury have achieved more than most at the pinnacle of the sport. The travelling community has watched them claim World titles and represent their culture on pay-per-view events worldwide. Boxing was always a part of Andy Lee’s life and despite previous claims that he hadn’t craved a career as a trainer, he seemed the perfect fit. It was a cruel sport at times, with boys slipping through the net and never truly delivering their potential. Money came and went, with job security a myth, for most. His achievements throughout those eleven years as a professional were admirable, with many more to follow from the safety of the stool. But it could have all been very different.

I had been in contact with Craig McEwan a few months ago – a name unfamiliar to many. With hundreds of amateur fights to his name, he moved to America, linking up with Freddie Roach and training every day with Manny Pacquiao, Miguel Cotto and plenty of other generational talents. McEwan now lives back in Edinburgh, trying to drum up interest in his own little amateur gym and telling stories of his time in Los Angeles. Andy Lee fought Craig McEwan nine years ago, with the winner set to almost certainly move on to World titles and bumper pay-packets. McEwan was winning, boxing excellently until Andy dug deep and stopped him in the final round. ‘Maybe that was the difference,’ I thought.

That was boxing. The highs and lows of the loneliest sport, played out under immense pressure. Everything can change in an instant; with a clean shot to the temple, staggering your senses or with a broken rib suffered after a thudding blow just above the belt line. Andy Lee knew that his career could have taken a different route – he was thinking about it during the later stages of that fight. But he couldn’t allow himself to lose. He wouldn’t submit. Now, with his name etched in boxing’s history of World champions and with videos of his frightening knockouts infecting the internet regularly, he can focus freely on other things. But he always finds himself drawn back to boxing.

“I can remember clearly in the corner saying to myself, ‘No, I can’t let this happen.’ I just changed and I’d never really did that before, but I just put my hands up and walked forward and just started taking these shots on the gloves. I was just trying to bully him and then eventually, wore him down and got him stopped in the last round. But the fight was very close, and I’m sure he thinks about it a lot and how different his life would have been and his career would have been could he have just hung on that last round, because he probably would have won. But that’s boxing, isn’t it?

“So much depends on the outcome of a fight, it’s not like any other sport, and it’s not just a sport, it’s a livelihood and if you win you move on, you keep progressing and who knows what that might lead to. But if you lose it’s a major, major setback. It takes a big person to come back from a loss, especially a big loss like that on TV, when two young guys fight, one [McEwan] was undefeated at the time. There was a lot on the line. I knew, had I lost that, I wouldn’t be here today living in this house now. Who knows where I’d be?”

Interview written by: Craig Scott

Follow Craig on Twitter at: @craigscott209