Sweden hasn’t typically been a country known for its boxing, of late. Of course, former heavy-handed champion Ingemar Johansson of Gothenburg, shocked Floyd Patterson, stopping the American heavyweight sixty years ago. However, the country placed a thirty-six year ban on boxing, only lifting it partially in 2006.

More recently, Badou Jack has spilled plenty of blood, winning world titles in two divisions – yet is one of only three Swedish men to reach the pinnacle of the sport. A focus on other leisure activities, such as handball, football or golf have hindered the next generation of Swedish boxers.

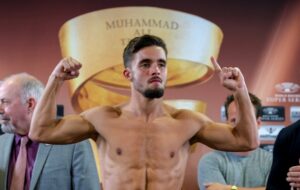

As another eight-man tournament rapidly approaches, former world title challenger, Anthony Yigit (24-1, 8KOs) was excitable, when discussing his return to the ring. Starring in one of last year’s most striking images, Yigit’s eye had ballooned grotesquely during his World Boxing Super Series quarter-final with Belarusian former IBF champion, Ivan Baranchyk. But that was then and this is now.

Ahead of the next instalment of MTK’s ‘Golden Contract’ tournament at light-welterweight, Yigit was keen to discuss his recovery from that injury and his introduction to boxing, whilst living in a city that often turned the other cheek. He is Swedish, by birth, of course. But a cocktail of different nationalities had given Yigit exposure to various walks of life.

“I’m going to tell you the whole story”, he began, “I’m from a Russian family, they are Jewish-Russian, yeah. My Finnish family, they are originally Swedish and my Turkish family I think, obviously in the Middle East they moved around a lot from the Middle Ages and stuff like that, so my Turkish family we are originally from Syria I think, or Lebanon, I’m not quite sure. I don’t remember, really.”

“We are from this tribe and it’s a whole messy story. Look, if I wanted to check my heritage it wouldn’t be possible. But I’m always saying, ‘I’m a Jewish-Muslim from Russia, Turkey and Sweden’. That’s where I come from. You put some of this and some of that and you get a really nice drink, and that’s me.”

This Jewish-Muslim from Russia, Turkey and Sweden sounds like an intelligent Englishman at the other end of the phone, speaking as well as any international fighter. After hearing stories from former training partners or members of the media who’d dealt with Anthony, it was clear he understood the value of telling his own story. Boxing hadn’t always been a part of his life, it drifted in and out as Yigit continued crossing borders.

“I was staying with my mom, because my mom and dad split up when I was young. She remarried and my sister came from that relationship, but then they broke up. She got married again and my two other siblings come from that [relationship]. She stayed with him for a long time, so he raised me and I always saw him as my father figure.”

“When I was twelve, I got to meet my real father and he asked me if I was doing any sports. I was doing judo at the time, but my dad said, ‘Listen, I know this boxing trainer’. I went there and I could train for free, but sometimes I’d train, sometimes I didn’t. Then my mum moved us to Turkey for three years. When I was fifteen, I decided to move back to Sweden and live with my father – that’s when I started boxing for real.”

Yigit hit the ground running once boxing had become his priority, excelling in the Swedish amateur system. He’d been uprooted countless times, crossing borders and also suffering a spell of homelessness when ending his career in the unpaid ranks. His father kicked him out and the phone stopped ringing. Offers from overseas that seemed concrete, soon turned to quicksand which gave him an early insight into life as a professional.

His time as an Olympian at London 2012 seemed to count for little, and despite being the first Swedish fighter to win a bout at the Olympics in over fifteen years, he played the waiting game. Before taking matters into his own hands, he was linked with boxing super promotion Top Rank, but decided to reach out to Team Sauerland, far closer to home. A powerful operation in Europe, particularly in Scandinavia, the company have worked with their stylish prodigy, guiding him towards commercial success and world titles.

Never quite settling in one area throughout his childhood, the wandering Yigit has already been based in various countries as a professional fighter, such as Sweden, Germany, England and Spain. He couldn’t enjoy home comforts – he was made to travel. In doing so, he’d beaten British duo Joe Hughes and Lenny Daws for his European title – bizarrely fighting the latter in little-heralded boxing town, Carshalton, Surrey.

The Swede’s clean-cut image and immaculate behaviour could potentially fool the casual observer. Until his fight with Baranchyk, Yigit hadn’t faced such adversity head-on between the ropes. That evening in New Orleans, ‘Can You Dig It?’ showed his mettle, disproving those who accused him of sidestepping Josh Taylor only a couple of years prior. The two could have infact been drawn together, however the IBF had opted for Baranchyk v Yigit to contest their vacant title – ironically now held by the Edinburgh-man.

Recently returning from his warm weather training camp in Las Palmas, Spain, he was now primed and ready to tackle some of the division’s best fighters. Ohara Davies, Darren Surtees and Mohamed Mimoune are amongst potential opponents for Yigit, preparing to fight at an adopted second home in York Hall, Bethnal Green. Opponents didn’t bother the former European champion and losing was just a consequence of hunting success. Strangely, though, a tattooed Northern Irishman had caught his eye during the build-up.

“Here we are now, approaching this ‘Golden Contract’ tournament and Tyrone McKenna, well actually he’s quite new to me. I didn’t know who he was before, but I watched him fight, he is a terrific fighter and I think the tournament is really gonna be a blast. Sky Sports are going to cover it, so I like that. It shows everyone that, okay, I’m still in the game, I’m still hungry and I’m still looking to be a world champion.

“That’s what we do this for. We are supposed to fight each other”, he added. “We are supposed to fight whoever comes in front of us. If you don’t, you’re not a real champion, and that’s my mentality. I’m not scared about having a loss or two losses. For example, my loss is from this injury. A doctor stopped the fight, so I didn’t lose. I didn’t lose against one of the hardest hitters in this business. After the fight he was a world champion, and I didn’t ‘lose’.

“Would I be embarrassed to lose [again]? No. I’ll make sure that, hey, I didn’t lose because I’m bad, I’m losing because I’m one of the best fighting against the best, that’s why. You’ll always see me fight the best, because I belong there.”

The sense of belonging wasn’t familiar to Anthony, after spending so long finding his feet as an adolescent. To fully understand that boxing provided his stability had only strengthened his love for the sport. Yigit realised he could infact achieve what many others could only dream of.

The ‘Golden Contract’ is staged four weeks after the conclusion of the light-welterweight World Boxing Super Series, with only a twenty minute tube journey between both venues. Josh Taylor faces Regis Prograis at London’s O2 in a unification clash, set for Box Office. In many ways, the Swedish family man’s entry into the tournament had been a ticket to the big time – relatively short-lived.

As a beaten quarter-finalist, Yigit was looking forward to its conclusion, remembering his selection fondly. The beams of platinum light shooting upwards and the smoke-filled podiums had taken boxing by storm. It just didn’t quite go to plan. Many felt he was edging himself into a slender lead during the fight, but the damage had already been sustained. It was painful, watching the enormous welt swelling by the second, continually being targeted by his opponent.

“It’s always a dream come true just to partake in such a big event and the World Boxing Super Series seemed to be the center of attention”, explained the twenty-eight year old. “Now it’s going to be big again, when Josh Taylor fights Regis Prograis. It was just a big honour to be on that stage and to be fighting with these world-class fighters. I got to fight Ivan Baranchyk and it was a great fight.”

“Watching it back, I can see some things that I need to work on, that I maybe overlooked. If I really want to be able to break through and make it in the big leagues, and be a world champion, I need to work on certain things that I didn’t work on before. I just know that there is a reason I didn’t win and I need to fix that.”

“To be honest with you, we knew [the injury was coming]. I had problems with not only that eye, but my eyes, because if you look back on other fights, my eyes tend to swell up. We said before the Ivan Baranchyk fight, ‘Yeah, okay, so we need to just put ice on the eyes from the beginning and make sure they don’t swell up.'”

“You can see me complain to the doctor, it’s because I was like, ‘Hey, my eye’s been shut for quite a while, so if you wanted to stop the fight why didn’t you stop it earlier? If you didn’t, then just let me continue.’ My coach actually said, he was like, ‘Well, listen to me, trust me, it’s not looking good.’ After, I went down to the changing room and I could see my eye, and then I was like, ‘Oh, okay.'”

With his eye almost as big as his heart, the damaged fighter was determined to continue. It was never going to happen. At the time of writing, we keep Patrick Day in our thoughts, a fighter that battled and battled, ultimately taking far too much punishment. Boxing is a sport, but it’s often a brutal meeting of machismo and misjudgement.

“I mean, now that I think back to it, I’m at peace with it. I’m not the kind of guy that has to have a spotless record and I just believe… it’s not the end of the world. I still have the chance to be a world champion. I’m young, let’s just take it from there.”

“With that being said, would I take the chance [and continue]? I would, but if something would have happened I would have looked at someone else to blame. Obviously then it’s not really my choice to make, is it? It is the doctor’s choice to make and he made it.”

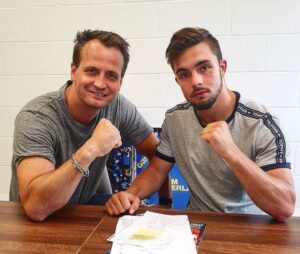

That choice was taken from one of Yigit’s dearest friends, countryman and mentor, Erik Skoglund. The pair had just finished training together in Spain, with former light-heavyweight and super-middleweight contender, Skoglund, continuing his remarkable rehabilitation. He suffered a serious brain injury after a routine training session, something that had shaken up boxing, especially in Sweden.

The nation that had previously banned boxing seemed vindicated as stories of Skoglund’s condition circulated the national press. Erik was like an older brother to Anthony, with the pair standing side-by-side for the last decade. Given the severity of his own injury when fighting Ivan Baranchyk, it seemed strange that Yigit would have wanted to continue. But fighters were a strange breed after all.

“The weird part is, I wasn’t afraid about him not waking up. I was more afraid about how he would feel when he did wake up. Because boxing has been his life and one day, you just wake up and they tell you that you can’t do it anymore. It’s heartbreaking. You invest your life into it and then somebody tells you, ‘Okay – no more boxing’. I’m just sad about that. Erik really struggled coping with that.

“Bleeding isn’t so hard. It’s easy. You get punched and you bleed. The hard part about being a fighter is going through something like Erik has went through. Continuing to push through and look at him now. He’s back and he’s been training with me. He’s crazy. That’s a real fighter.

“I decided I would make him a part of my team and Erik tells me that he’s never been more alive than when I bring him to the fights. He can be in the corner – even though he can never fight – but as long as he’s in that environment, he feels as though it never left him.”

With Erik Skoglund by his side, Yigit seemed stronger than ever. The inspiring story of the boy thrown from pillar-to-post, travelling from Sweden to Turkey and back again, was yet to reach its conclusion. He’s been given a second chance, preparing to compete for the ‘Golden Contract’, yet boxing was deeper than that for Anthony.

He spoke with passion and dissected the sport’s flaws, opening up over the struggles he’d faced mentally, stemming from the isolation forced upon fighters. When he wanted to socialise, nobody was interested. Friends and family had been unable to connect due to rigorous training schedules and time spent overseas, locked away, punishing both the body and the mind.

Becoming a world champion remained his priority – that much was clear. Yigit understands that fighters are often forgotten when the final bell tolls, but legacy can last forever. This seemed important to him. For his family, the wide range of ingredients that produced a ‘nice cocktail’, for Erik – who’d been stripped of the opportunity – and for himself. The journey was far from over.

“I want people to say that I never backed out of a fight. I want to make an impact, for the crowd. I don’t want people to say, ‘He was a champion, but he didn’t fight the best’, or, ‘He was a coward’. I want them to say that I was an inspiration and that they wanted to watch me fight.

“Look at Arturo Gatti v Mickey Ward. Who won those fights? Nobody really cares. They just wanna watch those guys fight every time. They watch the highlights over and over again. That’s what I want. I want them to YouTube me [when I retire] – whether I win or lose, I just want them to watch.”

Interview written by: Craig Scott

Follow Craig on Twitter at: @craigscott209