As little James McGirt sat on the edge of a crumbling concrete step, looking out onto traffic, he’d found a certain sanctuary in isolation. When many others were wandering the street, enveloping themselves in mischief, he was far easier pleased. Despite the guzzling of gas and the emission of aggressive growling from the enormous engines that sped past his Brentwood home, it was often his own definition of peace.

One of six children raised admirably by a single mother in Long Island, he’d always been amazed by trucks. Big, powerful and unrelenting when placed beside regular Cadillacs or Chevrolets, the young man who shared his birthday with boxing royalty such as Muhammad Ali and Cus D’Amato, was captivated. With their tires pounding the tarmac and with wheels that matched most of his classmates for size, James had spent hours just glaring longingly at that tiny, almost personal portion of their long haul journey. If he could afford one now, he’d turn his back on boxing. Maybe.

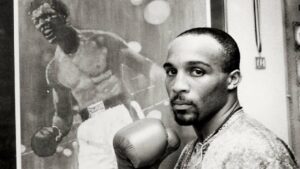

After outgrowing the steps on his mother’s porch, James became ‘Buddy’ McGirt (73-6, 48KOs). A product of impeccable parenting from his mother, Dorothea Boynton, he’d go on to achieve everything possible in boxing, capturing world titles in two weight classes before adding championships as a trainer with various fighters including Arturo Gatti and Antonio Tarver, most recently leading troubled Russian light-heavyweight Sergey Kovalev’s charge at redemption.

Now, in June of this year, over twenty-two years after his last contest, McGirt shall be inducted into the International Boxing Hall of Fame. The kid from Brentwood still retained a loveable innocence when interviewed exclusively for Boxing Social ahead of the ceremony in Canastota, New York. He laughed as he reflected on a career which had its fair share of ups and downs, yet still displayed a fascination for articulated vehicles, dragging him back to simpler times.

“I’ve always loved trucks. I tell everybody, if I ever get my hands on a couple of million dollars, I’m gonna buy a rig and I’d love to drive it. I’d just have it, driving down the highway acting like I’m King Tut! Daring somebody to pull infront of me (laughs). I used to sit infront of my house and watch them drive by. Anytime there was a movie or a TV show about truck driving, I was right there infront of the TV!

“As a kid, right beside my house there was this big company and they used to deliver stuff to supermarkets all over New York. One of their main places where they parked the trucks was right next to my house – so they passed the house every day. I’d just stand out there and watch them go by, I loved the way they sound.

“I know that sounds crazy, but that’s what I used to do. I just fell in love with em’. I wanna own one, even just for a week. A friend of mine taught me how to drive one, but that was with the trailer. I just wanna drive it, I’m not trying to pull nothing [behind me]. I’d get one with a bed in the back, so I can throw in some jeans and some boots.”

As Buddy continued to romanticise life on the road as a trucker, the shrill, piercing sound of the timer in the Californian gym sliced through our long-distance call. It was unnerving and brash, yet he never seemed to notice it – continuing to wax lyrical about his plans after he’d finished with boxing.

It’s always the sign of a man conditioned to the sport, unmoved by the pandemonium or the prevailing smell of the gym – just part of the furniture. He’d been working that day primarily on media calls, rallying websites and sports papers before his induction.

McGirt had fought professionally for fifteen years, many of which were spent battling at the highest level. He’d decorated cards in meaningful contests against some of his generation’s biggest names, throwing caution to the wind in both the light-welterweight and welterweight divisions.

Securing a maiden world championship against the unbeaten Frankie Warren, a musclebound brawler from Corpus Christi, Buddy had achieved what he’d originally set out to, when training as a kid in the Brentwood Recreational Centre with trainer, Gene Moore. But boxing wasn’t for him, as he revealed during an emotional discussion about the importance of family.

“It was about my mother. I’m a’ tell you a true story. We went to the supermarket as kids, I was a kid and my brother had a field trip. My mother was buying her stuff and she bought herself some panties [underwear], so we got to the cash register and she didn’t have enough money. She had to put these brown panties back, so my brother could have stuff for the field trip. We go home that night and my mother had washed and hung up [another pair] so she could wear them to work.

“I was a kid, but I thought, ‘Damn, that’s not right’. So, when I became champ in ’88, I went to JC Penney’s, the department store, and I spent two grand on bras and underwear for my mother. When I got home, I threw them all on the bed and she said, ‘What the hell is this?’ I said, ‘That’s for you’.”

Fighting tears whilst perched on the ring apron, he continued, “She said, ‘What the hell am I gonna do with all this underwear?’ and I said, ‘You can change them every day, you can change them every hour if you want to’. I told her the story and she couldn’t believe that I had remembered that.

“As crazy as it may sound, boxing, yes I wanted a better life, but I wanted a better life for my Mom. I figured she raised me to be a man, so I’m always gonna find a way. I used to get her a new car every year. She raised six kids and gave up a lot for us, by herself. I only wanted the best for her. It was about me, but it wasn’t about me.”

Life in their family home back in Brentwood had been full of love, as he shared it with his siblings Harold, Michael, Wesley, Daniel and Elizabeth. After losing his mother only a few years ago, Buddy had been keen to continue achieving, in memory of his heroine. He wanted to make Dorothea proud after all she’d sacrificed, yet as a parent himself, I was sure he’d do exactly the same for his own children. The values she had instilled weren’t lost and I sensed, after sharing those precious memories, that there was no one he’d rather have taken with him to Canastota. His mother had made him a man – boxing had just helped toughen him up.

Now aged fifty-five, his entry into boxing had been a result of a bout of jealousy, triggered innocently by encounters with a cousin from New Jersey. His Uncle would rave about his son, training and competing as an amateur fighter and the acclaim he continually received had suddenly sparked young Buddy’s competitive streak, determined to fill his mother with that same sense of pride.

On approaching Brentwood Recreational Centre for the first time, he was told he might be too small and that sessions were run on Saturdays for kids aged twelve and above. No exceptions. The coach explained their next session was the following Saturday and asked if he could make it? ‘That’s my twelfth birthday – I’ll be there’, replied the innovative, future world champion.

“At the time, I was playing little league football” he explained, “One day I was standing on the side [of the football field], it was ten below zero, it was cold and I’m sitting there thinking I could be inside a hot boxing gym instead of freezing my butt off. So at half time, I gave the coach my helmet and said, ‘I’ll bring the rest of the stuff back on Monday!’ I walked home (laughs). It was too cold to be standing there chasing a football. It was different because in football, it’s a team. I played defence, so you gotta worry about the offence but you don’t really have control. In the boxing ring, it’s just you and the other man. Boxing, to me, is more competitive. It’s one-on-one.”

He’d had his fair share of gruelling contests, losing twice to fellow great Pernell Whittaker which still seemingly bothers him to this day. Despite a career which delivered so much success, McGirt was aware he had his detractors, whether it be for his time as a fighter or more recently in the corner of some of the sport’s most complex characters. He told me he doesn’t give a damn about those who criticise him from afar, preferring to pour his energy into people that matter, such as his family or his fighters.

I’d been keen to understand his thoughts when reflecting on his own career as a prizefighter, as now he views the sport from between the ropes as opposed to shirtless, standing inside of them bearing his soul. It was tough to gauge his satisfaction, as he selflessly referred to pleasing others in a way which was becoming habitual for a traditionally good man. His career had been a vessel fit for change, flipping family fortunes and earning the respect of a sport which often evokes disloyalty.

“I learned the hard way. Nothing was ever given to me. I thank God I did, because it helps me today. You get people trying to BS you, but I’ve seen it all. I came up in the time where my manager was one of the roughest in boxing. He always told it like it was. If you didn’t like it, you were in the wrong business. They didn’t kiss anybody’s butt, they didn’t care who you were, they said it how it was. I learned from watching them, because they never kept nothing from the fighters.”

“If there was $10 on the table, then they’d know there was $10 on the table. We took fights at short notice. They would call up and say, ‘I gotta a fight for you guys, we’re gonna pay $2’. Now if you say, ‘Hang on I’m gonna call you back’ then they’re gonna call someone else and offer $1.50 – that next manager would take it. ‘Sorry, we got somebody else’. If you wanted to fight, if you wanted that money, then come get it.“

He told me, “It’s not a sport anymore. It’s more of a business. They’re taking the fun out of it. I mean, they’re starting to have a little better [quality] fights, but it’s not the same. I personally believe they should bring back fifteen round fights, that’s when you separate the men from the boys, those last three rounds. I think fighters would take it more seriously. If you can fight ten rounds, the other two is nothing to get to the twelve rounds. If you fight ten rounds and you got five more to go, they’d have a whole different attitude. Today, boxing has got to the point, you can look and see who’s in each corner and you know who’s gonna win.”

Buddy fought eighty times as a professional, a figure unlikely to be replicated in modern boxing. Despite losing to Sweet Pea, he racked up important victories against former world champions, Simon Brown and Livingston Bramble, also defeating my countryman, skilled Scotsman Gary Jacobs, comfortably. I’d read somewhere recently that Jacobs felt McGirt was a better fighter than Whittaker, whom the Glasgow man had also fought during an impressive stint at the top of the welterweight division.

Only a year after retiring in 1997, the champion from Brentwood was inducted into the New Jersey Boxing Hall of Fame, something he remained immensely proud of. But this recent announcement, the result of a ballot, and the event which runs for an entire weekend at the beginning of June was in a league of its own. It was an elite school of boxing’s greatest servants, with many taking the sport to a different level.

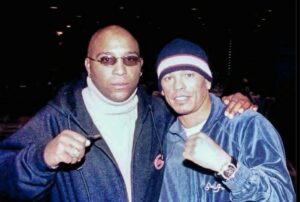

Buddy was about to join fellow inductees such as Willie Pep, Sugar Ray Robinson, Julio Cesar Chavez and of course, his old foe, Pernell Whitaker. However, he’d be joining one man particularly close to his heart, a close friend originally named Arnold Raymond Cream.

”I used to get visits from a lot of former fighters when I was a kid and I’d just turned pro. But I became really good friends with Jersey Joe Walcott and he used to come down from Camden, New Jersey to watch me train. This is a man who could do something else with his day, but he’s driving two or three hours to watch me train, a former heavyweight champion of the world. One day he told me, ‘Kid, listen, if you keep your nose clean, you’ll be a world champion!’ I met him first when I was thirteen years old, but I didn’t know who he was, I was just a kid. He signed my autograph [paper] – ‘Arnold Raymond Cream’ – which was his original name.

“When I turned pro at eighteen, I met him and he was good friends with my manager. That’s when I started doing my research on em’. We didn’t have no tape like there is now. I couldn’t go to YouTube and watch him, I just had to go off what I could read. Then one day, I met a guy who had a lot of fights on tape. He had some on Jersey Joe Walcott and I went and watched it. It was great, the greatest feeling in the world. Of all the fighters in the gym, he was coming to see me. He made that obvious cos after training we would go to lunch – he never went to lunch with anyone else. After I won my first title, he was there. He was a great man. After he passed away, I went to his wake in ’94, there was a blizzard but we still drove down there.”

Loyalty wasn’t lost on McGirt, who told me his friendship with heavyweight legend Jersey Joe Walcott was his ‘best moment in boxing’. There had been many, in reality, from lifting both of his own world titles to watching his fighters succeed when operating as a trusted head trainer.

Recently, his career had been resurrected after a call from Egis Klimas, manager to exceptional Eastern talent such as Vasiliy Lomachenko and Oleksandr Usyk. As he accepted the offer without hesitation, the role of training notoriously troubled and recently deposed light-heavyweight champion Sergey Kovalev, the stars aligned and Long Island’s favourite boxing son returned to top form.

Beating Eleider Alvarez, who had previously knocked him out when brutally claiming his WBO world title, had thrown Kovalev back into the mix at the twilight of an impressive, intimidating career. Long thought of as a bully amongst his fellow 175lb peers, he had punished opponents despite being rumoured to have trained himself after splitting with John David Jackson. McGirt explained his tenure with the Russian was entirely pleasant and professional, with years of experience contributing to their performance.

“A lot of people doubted him [Kovalev]. They doubted me, but I don’t care what people think of me, you can think all you want. But I was proud of him because he did everything I asked of him. Before I started training him, a lot of people said, ‘It’s not gonna last, you can’t tell him anything, he’s stubborn’ but when I met him, the first thing he told me was what he did wrong preparing for the first fight. He admitted to me what he did wrong and I gotta respect that. He didn’t have to do it, but he did and the rest was history. It took him a couple of weeks to get adjusted to what I wanted him to do, but a lot of the credit goes to him. He was willing to listen and he stuck to the plan no matter what.”

Buddy McGirt famously told the boxing media years ago that the sport was missing ‘teachers’. Holding mitts or setting up flashy drills looked great on video, but what were these guys teaching their fighters? He explained the importance of learning and listening, simultaneously.

His future with Sergey Kovalev, or with professional boxing in general was never certain. During our time together, he revealed his desire to open a gym which could solely work with Parkinson sufferers and children. No ego, no contracts, no bullshit. He wasn’t quite ready to step away from the game yet, but he’d seen enough to last a lifetime.

I wondered if little James, from that crumbling concrete step in Brentwood, had ever expected this? He tells me, ‘No’ without skipping a beat. Despite the grey hairs now visible in his infamous goatee beard and perhaps the addition of some weight since his fighting days, he remained that same fascinated kid, watching the traffic with his eyes fixated on the freedom of the open road.

James, who spent his afternoons watching those trucks pass by from the local depot, full of intrigue, had made his mother proud, and as I looked at the weather forecast for his big weekend in Canastota, it read pure sunshine and warmth – maybe she would be with him, after all.

“Ed Brophy always calls me to be a guest at the Hall of Fame. So, he calls me and just keeps talking and hesitating, I said, ‘You wanna get to the point, Ed?’ Then he told me. He said, ‘I wanna be the first to congratulate you’. It was a great feeling, I started crying like a baby. To be in the same category as some of the greatest fighters ever, it’s something they can never take away from me.”

Interview written by: Craig Scott

Follow Craig on Twitter at: @craigscott209