The streets of Toxteth, Liverpool, overlooked their own sense of irony.

In the eighties, south of the city centre, its streets were infected with racism and civil unrest. Immigrants from a variety of Commonwealth countries had settled post-World War II, broadening the demographic for the generations that followed. From fighting on the streets to sharing their television screens, the multi-cultural residents of the notoriously tough, suburban area united to celebrate a common interest. Boxing.

Light-heavyweight world champion, John Conteh was one of the city’s most popular fighters, rightfully considered amongst its best. He was the son of Kirkby, and of mixed heritage parents, with his father hailing from Sierra Leone. Not too dissimilar, when compared with modern British boxing figurehead, Anthony Bellew, who also scaled the sport’s dizzying heights.

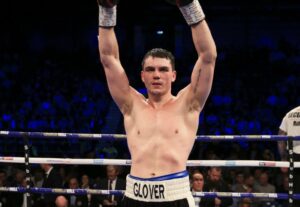

Liverpool had always been fond of tough, genuine, fighting men – banding together to lace their gloves against cultural and economic adversity. Craig Glover (9-1, 8KOs), one of eight boisterous brothers, was filled with the steely determination often seen in the city’s working class success stories. Family connections run as deep as the Mersey, with the knockout artist confessing his entry into boxing had been expected, born into a household of competitive siblings.

“I was a typical kid. Don’t get me wrong, I come from a big family”, he told me. “So, obviously there’s the usual stuff. Sometimes you get in trouble. I wasn’t a bad kid, like, I just went around with me’ brothers and everyone around here knows us. I was just a normal kid. Every so often we’d get in trouble with things, but I was generally well-behaved.”

“I’m still based in Liverpool now. I think it’s always been a thing, a culture. We’ve always had that fight culture, always had gyms and we’ve always had people coming through. Footy and boxing, they’re the two big things we’ve always had and we really try to support our own. It’s good, like.”

Whilst boxing brothers Paul, Stephen, Liam and Callum captivated fans from Liverpool and captured British titles, the Glover boys weren’t destined to follow suit. It would be Craig that would firmly focus on a career inside the ring, never one to shy away from a challenge.

Whilst growing up had seen him involved in ‘the usual stuff’, it was the focus of combat sports which would guide him to televised contests on Sky Sports, as recently as last October.

Carrying consistent power at domestic level, with an 89% knockout ratio, the shorter-statured fighter had first found success with his feet, as well as his hands. Similar to plenty of other wandering teenagers, his interest in boxing had been sparked whilst throwing kicks with his shins padded, searching for something to centre himself.

Glover explained, “Me’ family have always boxed and I did a little bit of boxing. I started with kickboxing. I was quite heavy at the time, so it was more-so just to lose weight. I was a little bored when I was a teenager, I lost a bit of weight and then I won a couple of things.

“Kickboxing, it doesn’t have massive depth or anything. There’s no place to go from it, you know? You can go towards the cage fighting or something like that – I thought I would give the amateur boxing a go [instead]. I had a few amateur fights and then left it for a little bit.”

It was at this juncture, that Glover’s stumbling and uncertain career was given a boost. The biggest name in the boxing city’s talent-pool, soon-to-be world champion Tony Bellew, had been known to a much younger Glover. But, it was through a chance interaction with a friend that their relationship was forged, with recently-retired Bellew becoming Glover’s manager.

“I started to put the weight on again (laughs), but just came back to [boxing] and I bumped into [Tony] Bellew and did some sparring. He said, ‘If you wanna turn over, I’ll give you an opportunity and I’ll look after you a little bit’. He’s my manager, yeah. Don’t get me wrong, I’ve known him for a while and I’d sparred him in the past.”

It takes a brief browse of the young prospect’s social media accounts to notice the support of the pay-per-view, headline attraction, Bellew’s support. Whether it’s a comment offering support or encouraging his charge to make that final push during an arduous training camp, no-one knows what goes on behind closed doors.

“It was the fight before the Masternak fight. He was left short for sparring and I’d bumped into a mutual friend of ours. He just said, ‘Bellew needs sparring’. This was Thursday or Friday and he said he needed sparring on the Tuesday. I just thought, ‘Yeah, okay!’ didn’t really think anything would come of it. I got a phonecall on the Sunday and they were like, ‘Aw, are you still sparring him?’ so I turned up and did the rounds, I think he was obviously impressed!”

“That was it”, he continued. “I turned over and he’s looked after me since. He’s one of these people, Anthony, he likes to help out people on his own, d’you know what I mean? I think he’d help other people out and he obviously knows the game. A lot of managers don’t have that. They go in with the best intentions, but they don’t have that [first-hand experience]. I don’t think he’d ever do it on a big scale, though.”

Now, back in training following his explosive win over Middlesborough’s Simon Vallily, the politely-spoken banger from Merseyside was only focused on improving.

The celebrations for stopping the former Team GB cruiserweight and highly-touted professional, were short-lived. It was Glover’s highest profile bout, yet the twenty-seven-year-old had remained focused on his musclebound task at hand, swerving the mind-games and indiscipline displayed by his opponent.

It was a coming-out parade, featuring on the televised portion of the Matchroom show in Newcastle, infront of a fanbase as equally fervent as his own. The fight’s duration was longer than he’d been used to, something he expressed gratitude for when reflecting on the event.

Glover had become all-too-familiar with figuring out his opponent, as they struggled to climb from the canvas, all within a matter of minutes.

“When I fought the first one [at the Echo Arena], the show started at half four. I knocked Ratu [Latianara] out in eighteen seconds. In the first minute. They kept the doors open and I was in the ring, no-one seen it. He was already knocked out and it was the best knockout of the night, on the Amir Khan bill!”

“I’ve been getting results, some good results! No-one has seen it. I was sorta’ glad it went eight rounds, I could show a bit more of what I could do, so yeah.

“On the run up to it, I had said I’d outbox him. I think people probably thought, when they seen us, like… Our records suggest, I’m probably the bigger puncher but they never say nuttin’ about me being able to box”, he elaborated, still beaming at the result.

“I never really had any amateur pedigree or nuttin’ like that, so I think people maybe thought he was a good boxer and a good mover, and that I’d try to have a fight with him. If anything, it was the opposite.

“Don’t get me wrong, he has some skills like and he can punch. Although his record probably doesn’t suggest he’s a big puncher, but he can definitely punch, like. He’s tough. These other cruiserweights, some of the shots he was getting hit with, there’s no way they would have took them.”

Craig is now a key player in an exciting division domestically, containing its hottest crop of British talent for many years. Often overlooked as a weight class, the emergence of Lawrence Okolie and Isaac Chamberlain; the continuing graft of Wadi Camacho and the exciting domestic clashes that await fighters like Luke Watkins, Jack Massey and Arfan Iqbal, have ensured the interest of televised promoters nationwide.

Craig wasn’t precious when asked to pick his next preferred opponent, prepared to face the best. After suffering a novice loss over four rounds, he didn’t have that unbeaten ledger to protect, personifying the ‘come one, come all’ mantra of Liverpool’s fighters before him.

As with his manager, mentor and friend, Tony Bellew, Glover was here for the legacy. It wasn’t about easy money and plastic titles – though capital and meaningful accolades were expected to follow.

“I want another good name in March”, he stated, without skipping a beat. “Another top-ten [cruiserweight]. But then, yeah, I don’t see why I couldn’t go for the likes of Okolie or something towards the end of the year. Whether he stays at British level or not, I don’t know. Yeah, somebody like Camacho, I can’t see him wanting it. He wants to fight for the British and then is he done? He has his little payday and he can go. Would he wanna fight somebody like me who can knock him out before he gets his chance? I dunno.”

“I just wanna get titles and make the rankings. If he’s still there, Okolie, I’ll fight him – if not, whoever. I’d take [Arfan] Iqbal, someone like that. For ages, none of them wanted to fight each other, but we’re sort of getting forced to now and that’s better for the fans, watching better fights.”

“Now I’ve taken that step-up, all the fights that I’m gonna be in are big fights with the bigger names. So, I’ve gotta keep improving and I’ve been in the gym. I haven’t stopped, really, I just keep training and keep trying to improve, which I have. I’m just building on what happened in October.”

With October still fresh in the memory, rumours of a bout with Brixton’s Isaac Chamberlain were floating around only last weekend. It was a contest he’d be interested in – a stepping stone. Glover’s clean, powerful work inside the four corners of ring had attracted the interest of neutral boxing fans, slipping-and-sliding, countering with accurate shots.

With his next bout yet to be announced at time of writing, it seemed certain that excitement would follow. He described himself as ‘a boxer-puncher… but maybe more of a puncher!’, waiting for the phone to ring with details of his next assignment.

Though, certain areas in Liverpool are striving to escape their negative stereotypes, their people remain loyal. Regeneration has been a focus of the council, building newer housing and focusing on schemes to help the youth, in areas like Toxteth. It seemed a pipe-dream, in the days of John Conteh and the riots. Everything does, when you’re starting at the bottom. To believe things can change you must place faith in potential, something that Craig Glover has in abundance.

“I’ll be world champion. It’s pointless, otherwise. If you can’t see it, you’ll never be it. If you can’t say it… Obviously there’s different stages but you gotta be able to think you can do it. Otherwise you never can.”

Article by: Craig Scott

Follow Craig on Twitter at: @craigscott209