Everything was still. Everything except the panicked, adrenalin-charged chest of the young criminal, struggling to reduce its trembling, staring up at the foundation of a stranger’s home. The teenager had covered himself in dirt, desperately trying to evade the howling, tenacious Police dogs, searching for the unlawful on another cold, Houston evening. With mud covering most of his furrowed brow and shame drowning his body, the slowest of the Texan street gang drew breath, as quiet as a whisper.

Hiding beneath this building, a young George Foreman(76-5, 68KOs) experienced his moment of reckoning.

“I was always out during the night mugging people,” explained the Hall of Fame inductee, and two-time former heavyweight champion. “Two friends and me, we robbed some people on that evening, and the police got behind us and chased us. I didn’t really look at myself as a thief, until that moment. I realised I was trying to cover myself from dogs, and I decided right then that I was going to change my life. I had to do something better. My mom had not raised me to be a thief, and that’s what I had come on to be.”

“If you’re going to be safe and have a good upbringing, you’re going to have to have a mother and father. I guess the big city didn’t hold hands with my mom and dad. They broke up when I was just a little boy. It was just my mom trying to keep me in line – and work – keep me in line, and it just didn’t work. I got to be a bad boy, only because of the lack of full-time parenting.”

George was speaking from the comfort of his ranch back in Marshall, Texas, purchased in 1976 ahead of his rematch with ‘Smokin’ Joe Frazier – which saw ‘Big George’ triumph, stopping the Beaufort-native in the fifth round. Marshall is dubbed the ‘Athens of Texas’, and the small city located in the State’s North Eastern sector was Foreman’s place of birth, though he stumbled into a life of crime in Houston, fending for himself after dropping out of high school.

Boxing wasn’t always a part of the plan, but with Foreman convincing his mother to sign him up to the Job Corps at sixteen in pursuit of legitimacy, his love of sport and his street-wise reputation were soon combined. George explained how he had listened to Muhammad Ali’s fight with Floyd Patterson on the radio in 1965, never dreaming the pair would be squaring off just nine years later in Kinshasa, Zaire, in what is still considered boxing’s most famous, championship contest.

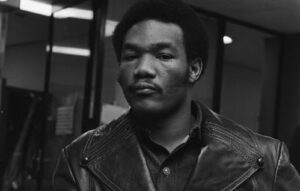

First though, he had to give it a try, telling me, “I had joined the Job Corps centre in Grants Pass, Oregon. The kids all looked at me and said, ‘George, you think you’re so tough, why don’t you become a boxer?’ That statement is what drove me to boxing. I changed Job Corps centre specifically to one in California so I could become a boxer. I heard they had a boxing team, so I found the trainer, he invited me to the gym and I was down to learn.”

“That was the beginning of my boxing career. It wasn’t like going into a regular boxing gym, though. The gym had basketball, volleyball and boxing [going on]. They only had this little boxing ring. Basically, I figured I was going to learn how to box, go back home to Houston, Texas, and be a better street fighter. I didn’t really want to be a boxer. That coach stayed with me to win another Golden Gloves. My first fight was in February of ’67. Then by 1968 I was already a part of the United States Olympic Team. It happened that quick.”

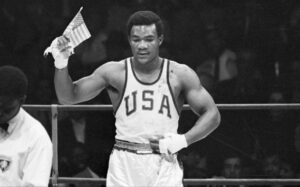

After just 20 amateur bouts, Foreman travelled to Mexico City to compete in the 1968 Olympic Games. He captured the gold medal, stopping three of his four opponents before the final bell, knocking out the vastly more experienced Soviet Union representative, Jonas Cepulis in the final. Waving his tiny American flag, held tightly inside his swollen, shovel-sized hands, George still describes this remarkable achievement as his proudest moment. He was a relative novice living out a fantasy, but, “punching was my thing,” he laughed.

“Punching is what I can do. Like everybody else, I wanted to be a fancy boxer, but then I’d look up in a boxing match and the guy was on the canvas, and the referee was raising my hand. I never did learn how to box, because nobody would charge at me. I had to go after them. I was an Olympic gold medalist after 25 boxing matches, that’s all I had. I think the punch was because I always had fear. I felt like a cat being cornered.

“I really wanted to be a baseball player, but I was always afraid I was going to get hit by the pitcher who threw the ball. But I could hit that ball really hard. When I’d get in the ring, the bell would sound and I’d always think, ‘Man, it’s like baseball. They’re getting ready to hit me with this ball.’ And I would throw my best punch to avoid being hit by them. I got one knockout after another. I believed that nobody could stand up to my punch. I just started to believe. The cowardliness had gone out of me. I really felt brave. I was no longer frightened like a cornered cat – I thought I could beat anybody, anywhere.”

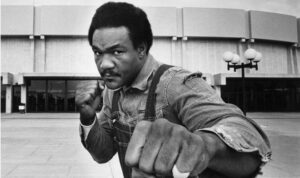

The young man who’d warmed the pavements of Downtown Houston, lost and without purpose, had found salvation between the ropes. Boxing became Foreman’s only path, long before the church and the unbelievable commercial success of his kitchen appliance-namesake. He was the brooding, brutal, heavyweight boogeyman, bludgeoning his way through the division. George Foreman was one of boxing’s most iconic figures then, with his moustache and short afro adding decoration to an otherwise emotionless face.

The Texan challenger would topple 40 opponents before shaking hands with defeat, stopping 37 of those victims – just lambs to the slaughter. Foreman stopped the previously unbeaten heavyweight champion, Joe Frazier in their first encounter, before knocking out Ken Norton in Caracas, Venezuela. He was the unified heavyweight champion of a World that almost turned its back on him.

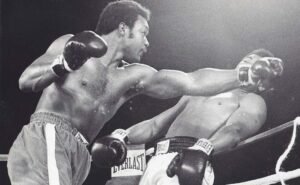

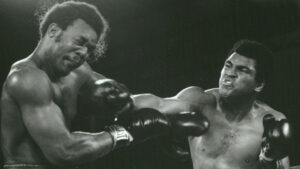

His fight with Muhammad Ali, arguably the most prolific name in all of sport, came in 1974 and George knew he had looked into the eyes of a man without fear or trepidation, soaked in confidence and striking charisma. Ali had beaten an equally-intimidating Sonny Liston, before facing prison and being stripped of his right to compete. As strong as Foreman was physically, Ali matched him when it came to mental fortitude and alarming durability. The defending champion never considered the Louisville-man a proper challenge but, on that sweltering evening in Africa, the pair made history.

“I really considered the fight with Muhammad Ali to be the least of all fights I would have had as the champion of the World,” stated the reflective Foreman. “I thought Frazier had beaten him, and he had given me no trouble. Ken Norton had beaten him, and he had given me no trouble either. I really thought Muhammad Ali would be the easiest fight. The only task I would have in fighting Muhammad Ali, I thought, would be to knock him out without hurting him. But then, around the fifth round, I realised, ‘Hey, this guy’s not going anywhere.’ By the sixth round, I was so tired, I could barely breathe.”

“I hurt him bad, and he would just revive. And he couldn’t come back and hit me, but he would revive and start saying crazy things, you know? I can’t figure out what he was talking about, but I always figured when a man is talking, it’s because he’s hurting. All the times I’ve fought guys and I’ve hit them with hard shots, they would recover and try to fight me back. He recovered and would just lay on the ropes. He just would not fight until about the six or seventh round, then he started to throw punches a little bit. I thought, ‘Great. He’s throwing punches. I’m really going to get him now.’ I heard Angelo Dundee scream from the other corner, ‘Muhammad, don’t play with that sucker.’ I’ll never forget it. When Angelo said that, he covered up again, and stopped punching. I never had another chance at it.

“I remember I got knocked down. I was told by Archie Moore and Dick Sadler, ‘If you ever get knocked down, don’t listen to the ref, find us and we will count for you.’ I lifted my head up, I found Dick Sadler, and he waved me to stay down, to wait. As the count is going on, I’m thinking, ‘He’s finally knocked me down. Now he’s going to try to get me. Now he’s going to try to finish me and I’m going to knock him out.’ But when I jumped up, the fight was over. That’s the way we left it. That’s the way it’s always existed in my mind. So I never said, at one point, ‘He beat me.'”

Dick Sadler didn’t last, being sacked in the aftermath of the ‘Rumble in the Jungle’. His mistimed count had cost George Foreman the biggest night of his career, his World titles and a slice of that ice-cold reputation, built from his earliest days in Houston before lacing up his gloves. He explained how he’d been unhappy during the fallout from the fight, noticing things he didn’t like and losing faith in Dick’s management.

After sending Saddler packing, Foreman was determined to return to the ring, detailing a call he received when based in Livermore, California. Muhammad Ali placed the call and offered ‘Big George’ a shot at his old belts, but only if he welcomed Saddler back into his team. The bizarre request threw Foreman, who remained steadfast. The pair would sadly never fight again.

Foreman fought only six times post-Ali, ending that run – and seemingly his career – with a points loss to a decent heavyweight, Jimmy Young, in Puerto Rico. The result was classed an upset, but the deposed champion only fought to prove to his detractors that he could go twelve rounds. His love affair with the sport that had rescued him from the streets had started to show cracks.

It was after his fight with Young that George recounts an explosive encounter with spirituality, “I went to my dressing room and had an experience. In a split-second, I was dead and alive in that dressing room. I lay in the room just screaming, ‘Jesus Christ is coming alive in me.’ I saw blood on my forehead and on my hands, and I never heard anything. I didn’t believe in religion, I didn’t believe in a God. Everybody talked about it. But I didn’t know it was a fact.”

“Afterwards in Puerto Rico, the smell of death, you never forget it. Even as I speak to you, it comes back alive in me again. That smell of death. I didn’t know it – I wasn’t prepared to die. For 10 years, that experience just reigned over my life and I became an evangelist. Opened my own church. I didn’t even make a fist for 10 years. I was a preacher. I didn’t even want to be known as an ex-boxer.

“After about two years, I cut my beloved moustache, my afro was gone, and I’d go out on the street-corner preaching. I didn’t want people to know that I was George Foreman. There’s two doors to this world; one is glamour, being heavyweight champion of the World and all of that; the other is just being a human being with the people you see every day. I had fallen in love with just being human. Going into the grocery store, when there’s only one steak, someone says, ‘Give it to the big guy.’ I became the big guy. I wasn’t George Foreman anymore.”

So it came to pass. The former, unified heavyweight World champion was now clean-shaven and draped in religious attire, preaching the word of God to anybody who would listen. He describes that decade as beautiful, finding peace in normality. Alongside his duties to the church, Foreman learned to fish, catching bass on his ranch and working closely with the horses he loves so dearly. George describes himself as a ‘natural-born farmer’, enjoying the tranquility of life in the country, protected from television sets and radio stations, using his time productively.

After being beaten by Jimmy Young in 1977, the religious fighter-cum-farmer, wouldn’t be seen in a boxing ring for 10 years. It just didn’t interest him. His passions lay elsewhere, feeding his hunger for spiritual redemption. But after a decade in boxing’s shadows, the money ran dry and Foreman was honest enough to admit his return to the gym was prompted by the prospect of earning fast cash with folded fists.

“I was in the church and I was speaking [to the congregation] to support my youth centre. And the preacher had me come down for three days, saying he was going to collect money for the centre. After three days, he sat down and asked people to give more money to help. They gave me some money. He said, ‘This is not enough to have George Foreman [here]. He’s helping our kids. Let’s give him some more money.’ I felt… just full of shame, sitting on a pulpit like that begging for money.”

Foreman outlined his initial plans for that unthinkable second reign at the heavyweight division’s helm, “I said right then, ‘I’m going to be heavyweight champion of the World again. That’s how I’m going to get the money.’ I glued myself to it, fastened myself to my integrity, and I promised that I was not just going to be the bum looking for money. I was going to be champion of the World.”

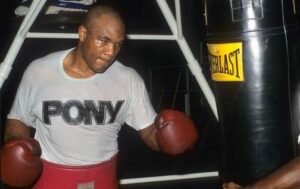

“From Joe Louis on, even Muhammad Ali and Joe Frazier, they all tried to make their comeback. But they all made the same fatal mistake. They wanted to come back to on top, like who they were when they left the sport. They didn’t honour boxing. You can’t start on top. If you’re going to come back, you got to start from the bottom, and work your way back up. I wasn’t interested in television shows. I went to little towns. Drew crowds sometimes, but in small places. I had to learn boxing all over again. I’d lost my quickness with parrying punches. I had to develop a new style.”

Returning in 1987, the fights came thick and fast. He boxed eight times in the first year, completing his anniversary with a stoppage victory over former cruiserweight World champion, Dwight Muhammad Qawi. Nine fights in the following twelve months told their own story; Foreman wasn’t back for a big, bumper payday. This wasn’t smash-and-grab. The Texan was getting to grips with his new physicality, honing his body to perform differently than it had twelve years prior.

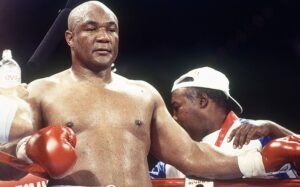

In April of 1991, four years after making the decision to fight again, George Foreman tackled reigning, undisputed heavyweight champion, Evander Holyfield. He lost on points. He would take positives from that encounter, telling me that in the championship rounds he could feel Holyfield tiring, ripe for one of those thunderous, ‘Big George’ right hands. It wasn’t to be. Neither would he succeed when challenging Tommy Morrison for his WBO heavyweight title over two years later, widely beaten on the judges’ scorecards.

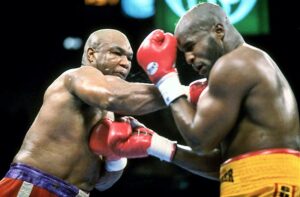

On the 5th of November, 1994, in the words of HBO commentator Jim Lampley, “it happened”. Foreman was drafted in to face Holyfield’s conqueror Michael Moorer in a fight dubbed, ‘One for the Ages’. When speaking about his contest with Moorer, George said, “If I hit him with one shot, he’d always come back and say, ‘I want to hit you back.’ He paid me back every time, because he was a lot tougher than I expected. He really was a genuine champion, you know? If you just don’t fade away, miracles can happen. And I lasted, and then I managed to get combinations away in the end to get that knockout.”

“I was so grateful. First of all, for the opportunity to come back, and grateful to God for giving me that opportunity. I even got on my knees and thanked God. I looked up to the sky and thanked God for what had happened. But I never looked down on Michael Moorer, because that was one tough fucker.

I had dreamed, and the dream had come true. And from that point on, you can only add to those things. Don’t get me wrong, but from the impossible, it was finally possible. I was running from the police one night, digging myself into mud, covering myself so the dogs wouldn’t smell me under a house, as a thief, with no hope. A crazy transition. That’s exactly what it was.”

I had dreamed, and the dream had come true. And from that point on, you can only add to those things. Don’t get me wrong, but from the impossible, it was finally possible. I was running from the police one night, digging myself into mud, covering myself so the dogs wouldn’t smell me under a house, as a thief, with no hope. A crazy transition. That’s exactly what it was.”

Foreman became emotional when reliving his historic victory over fellow American, Moorer. He explained the toughest thing he’d had to endure before his ten-year sabbatical was accepting he was, “one of those people who would forever be promised ‘another shot'”. That sympathetic pat on the back from promoters was a parting gesture, with most unwilling to risk their own fighters. George wanted a fair shake, but became lost and disillusioned with the business side of boxing. When beating Moorer that night in Las Vegas, an astonishing 20 years after fighting in Zaire, he had banished those demons, against all odds.

Fame followed, with the George Foreman grill gracing almost every household in the Western world – or so it seemed. I had one, I’m sure you did, too. Known for that endeavour by families globally, it’s hard to ever return to the anonymity he enjoyed in the eighties. Now, 71-years old and as sharp as a tack, the father of 12 is enjoying time in the countryside once again. Escaping the constant noise of the city suits him, perhaps blocking out memories of his early days, causing suffering or stealing from the innocent to provide for himself. It was just that, though: survival.

The man on the other end of the phone was fundamentally good, making amends time-after-time. I was happy to hear him speak so well, something former World champion, Glen Johnson rejoiced in, when I called him the following afternoon. Boxing gave George Foreman a way out. The focus required to master the trade demanded his attention, though it never promised him success.

Now, considering it’s been; 55 years since turning his back on a life of crime; 52 years since the ecstasy of Mexico City and his Olympic gold medal; 46 years since the pain of his ‘Rumble in the Jungle’ defeat to Muhammad Ali; 43 years since turning his back on boxing and dedicating his life to the church; 33 years since that low-key comeback fighting desperately for money and 26 years since becoming the oldest ever heavyweight champion of the World, toppling Michael Moorer, George Foreman just wants to be remembered simply…

“No adjectives. I would like for my story to be told on Mars and to inspire someone. Without any adjectives. Just George Foreman.”

Interview written by: Craig Scott

Follow Craig on Twitter at: @craigscott209