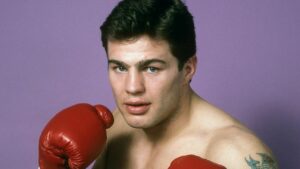

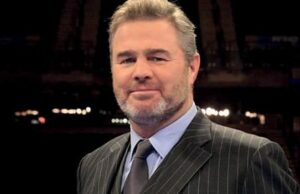

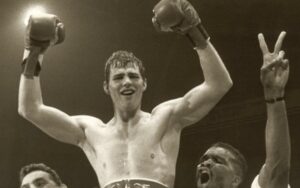

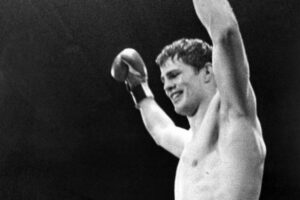

WHEN Boxing Social caught up with Glenn McCrory (30-8-1, 12 KOs) the former IBF cruiserweight champion of the world was knocking up a chicken curry. Hopefully he turned the fire off from under it as the 55-year-old was in a garrulous mood, covering his entire career from his time in the ring to his decades as a pundit with Sky Sports and other outlets.

Like the rest of us, McCrory is in lockdown mode, adjusting to a new way of life by utilising the experiences gained from his career as a fighter and his recent trips up Kilimanjaro and Mansalu. He scaled Kilimanjaro with Geraint Williams, who suffers from Fridriech’s Ataxia, a neurological condition that Glenn’s brother, David, died from in 1996. For the Kilimanjaro trip they adopted the name Team David as a tribute.

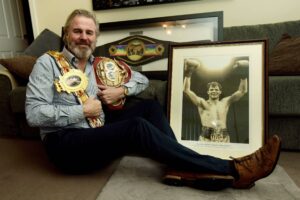

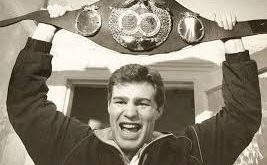

Everest was up next for the charity Children’s Christmas Wish List, but it has had to be put off for the time being despite McCrory auctioning off his IBF title belt in order to raise proceeds for the foundation.

Those long, lonely nights on the mountains are more hazardous than being asked to stay indoors for weeks on end. However McCrory told me that it is still a huge challenge for him, and the rest of us, to face.

“It is awful, to be honest,” he said. “You know what, I’m finding it really, really hard to get that routine going. You can’t get away from the news, can you, even when you go for a walk you come back and it is still there. I’m reading some boxing books to keep me occupied, I’ve got Joyce Carol Oates on the go at the moment.

“I don’t know how this will pan out in the end. If they slacken the lockdown then it comes around again with more cases do we go back down on lockdown again? We need a vaccine, a cure. Can you imagine another 15,000-16,000 dying? There is a care home in Stanley, where I am from, and another three have died in there the past few days. Care homes are starting to go now, once someone brings it in then they could be done because they are all in contact with each other.”

Like everyone else in the trade, McCrory is missing the day-to-day of boxing: life in the gym, life online, the gossiping, the rumours and the cut-and-thrust of what is a crazy sport and business. “I’m used to being in the gym training fighters from Monday to Friday,” he said.

“I’ll tell you what, having done the Himalayas recently, five weeks in a tent kind of prepared me for this. It was very lonesome. It gets dark half four or five o’clock and you are in the tent by yourself. It is a lonely existence, torture to be honest. It kind of prepared me for being in my own company and finding things to do. I just hope it doesn’t last much longer.”

“I was supposed to do Everest next, but climbing season has been cancelled anyway,” he revealed. “I took a friend up Kilimanjaro, which was a tough as you have terrible snow, drifts, avalanches going off — you hear about them every two minutes — and then you’ve got people going down the crevices. It is the hardest thing I’ve ever done. You think it is going to be great, but it is horrific, so, so hard.

“We think boxing is tough, people hitting each other and that sort of stuff, but doing this, it was just a case of praying every single day for the Lord to keep me alive and get me home. If you lose a glove, you’ve lost your fingers after 20-minutes — they are gone. Crevices open up all the time, you’ve got to get across massive drops using ladders, you are climbing with ropes all the time on something like Mansalu and Everest. It isn’t just a trek.

“I was nowhere in a million years prepared for it. The Sherpas were surprised that I did it. I think it was down to my years in boxing. When it comes to crossing a crevice you see serious climbers fall in and they have to whisk them out. I suppose having a cool head when standing across from the likes of Mike Tyson and Lennox Lewis does help relax you and prepare you for the job at hand. I was so grateful for my career and the hardships I had experienced for getting me through it.”

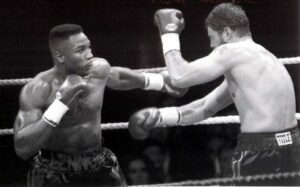

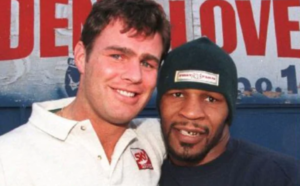

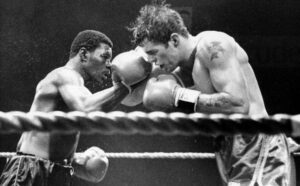

McCrory sparred Tyson when “Iron Mike” was rampaging through the division. He did well in the early spars, earned Tyson’s respect and was kept on for more of the same. Later in his career, and after the loss of his world title to Jeff Lampkin in March 1990 via a third-round KO, McCrory moved up to heavyweight and took on Lennox Lewis when he was more destructive than the fighter who Emanuel Steward finessed into a box-puncher of the highest order. McCrory lasted two rounds.

He once said that being hit by Lewis was like being hit by “Bags of wet cement”. Tyson’s power seemed to be spread across his combinations when at his best whereas, in my mind, Lewis had more one-shot impact. McCrory told me that they both hit hard in different ways yet the pain remained the same.

“One of the things was also the size, Lennox was a different type of athlete: tall, muscular and athletic — Mike was a little powerhouse,” he said. “Mike’s power would carry itself through six punches, and then he’d step to the side and hit you with three left hooks — you was under pressure all the time. Then you’d try to regroup and he’d be on you again. They are very different. Obviously, I still think that a peak Mike Tyson was on his way to becoming one of the greatest heavyweights of all time until the wheels came off. He was never the same after jail, still good, still fearsome, but not the same.”

“Tyson was different because we was sparring at his ferocious best around the time of [Larry] Holmes, [Tyrell] Biggs and Tony Tubbs, so he was right up there,” he said. “I got Lennox at his best, too, in a way and by that point my career was over in my head because I’d been ripped off for money that I didn’t get from my manager [Beau Williford]. With Tyson, it was very thrilling, you got a real buzz going in for those two or four rounds then someone else would get in. It was very, very tough.

“The hardest thing was you’d get through the day then realise you had tomorrow still to come. It was one of those where you’d have to keep yourself fantastically sharp every day. I remember a sparring partner who came over from England to spar and the first thing he said was: ‘What is it like? Where do you go out?’ I said: ‘Mate, there is no going out over here. You don’t go any clubs, I’m in bed at eight o’clock every night, up running at five in the morning — it is hell.’ He got knocked out in his first day of sparring.”

Tyson had his pick of sparring partners around that time, so it was eye-raising when he brought over and retained a cruiserweight from the North East who was not a player on the US stage, even more so when tales emerged that the British boxer was able to hold his own with the world Champion. It started badly for McCrory outside of the ropes, though, as he found himself arriving for camp dressed up in the kind of attire that hardly strikes fear into the heart of opponents due to a bagging issue en route to America.

“The first encounter was late at night,” he said. “I was knackered. I’d got to the airport at Atlantic City and my bag hadn’t arrived so I had no equipment. Luckily, I had my gloves and my head guard in my hand luggage. My dad had given me twenty quid as a present to go over with — we didn’t have much money — and then I met Mike who said: ‘Glenn, thanks so much for coming over to spar.’ They all thought I was mad, a cruiserweight going over to spar with Mike at his very best.

“I’d had some silly losses earlier on at heavyweight so I wanted to test myself. I was at my best at cruiserweight. The next day, I couldn’t come out and say I had no equipment and couldn’t spar, so I went to the boardwalk, and with my dad’s money I picked up some white shorts, a white vest and some plimsolls. You had Oliver McCall, Anthony Witherspoon, some big heavyweights, and I turned up with a string vest, shorts and plimsolls. Tyson must have thought: ‘What the fuck is coming here?’

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=9ivaaLmXXkc

“I did really well on that first day of sparring, I kind of realised that the secret, and, again, the most I ever did was six-rounds so it wasn’t life and death, was to keep him moving. Mike had knocked out Holmes, he had knocked out Spinks, but, and like all punchers, he needed to bend his knees, set himself to the ground, and get the power. Mike was no different. I just kept moving all the time, tried to stop him setting, and that is what got me through it.

“I’m there, I’m looking like an idiot, the other sparring partners are thinking: ‘This kid is going to get killed!’ Maybe I took him by surprise a bit. Maybe Mike got a bit complacent that first session, but as we went on at one point I gave him a black eye so Mike Marley wrote an article for the New York Post about it. You know, the skinny little cruiserweight who has given Tyson a black eye. That wasn’t the best idea ever because Mike wanted his revenge, you know, so the next day I got a six-round session!”

Fighters who have met Tyson say that he could not be more friendly and accommodating with his time. People who haven’t fought say that he can be sullen, unfriendly and we have seen some of the old video clips of him going at the media. McCrory found himself in a funny position as the years passed. Once his boxing career was over he became a pundit and commentator for Sky, which initially created a distance between the two.

“The strangest thing is that I saw that very much first-hand,” he answered when asked how Tyson was around the media. “I was with Mike as a kid with no money who was scratching a living and trying to get things going. The next time he saw me I had a suit on and was with Sky TV. I’ve never seen a guy look at me the way he looked at me, almost with a look of horror that I was now with the media.

“Sky used to send me over to get the interviews. This was post-prison when Mike wouldn’t give the media the lickings of a dog. He was a different animal after he came out of prison, he was very bitter after everything he’d dealt with. I’d get sent over there with Ian Darke and it was the same thing every time we went. We weren’t allowed in the gym. Then after a while we’d be let in. He’d ignore me totally during his workouts. Then he’d give me the odd nod and grunt at me a few times. Then he’d be like back to normal: ‘Hey, Glenn, how you doing?’ It was that same routine for the couple of years I commentated on his career at Sky.”

When Lewis and Tyson finally met in Memphis in 2002, an eighth-round KO for Lewis, McCrory pointed out in commentary that you cannot wipe away years of bad living with a single training camp. He said that Tyson could make himself look the part physically yet he was the shell of the fighter he once was, and not just because he didn’t live the life between fights.

“Nah, it wasn’t just bad living and not training properly, he just didn’t care,” he opined. “I think he had kind of lost the will to live and was on a suicide mission. I’m just glad he’s come through that, he’s a family man with a business who has got himself together. There was once a time when you couldn’t see Mike Tyson coming through to his 35th birthday.”

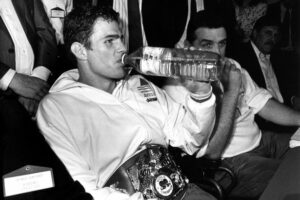

As for McCrory himself, despite his world title win he did not get the rarefied air enjoyed by boxing’s big earners. There is a common conception that every boxer you see on TV is raking it in, especially the world title winners, yet that is rarely the case. A small percentage of fighters earn huge money, the rest are earning just enough to clear the debts they accrue between fights and during their training camps. McCrory got £7000 for his world title win and says he saw just about half of it.

“I was working in a pub when I fought Lennox after being hit with an eighty grand tax bill, a sum I’d never got for a single fight in my whole career — Beau had all the paperwork so I couldn’t disprove it,” stated McCrory, revealing the reality faced by most fighters. In his first 19 fights, he won 14 and lost five while mostly campaigning as a heavyweight. The division just did not suit him.

“My manager, Beau Williford, had just left with most of my wages and I never saw him ever again after trying to get them back. I was treated badly. When I turned professional Beau wanted to train me himself yet he had no clue, all he wanted me to do was make me into a heavyweight to make more money so he hooked me up with Doug Bidwell [who had managed Alan Minter yet took a backseat to Minter’s true trainer Bobby Neill when it came to boxing matters]. I was a light-heavyweight as an amateur, I’d sparred Dennis Andries and done really well.

“Putting me in as a heavyweight so early was the beginning of the end. I was 18, 19-years-old and then the losses came. I left London to come home, was on the Dole and I was training in my living room. There were no professional gyms in Stanley, not really any amateur ones, and it was a mess of a career as I was working with my old amateur coach and my brother so it wasn’t great preparation. My career could have and should have been so much better, I won the world title without a proper trainer and didn’t have a proper career.

“Against Lampkin, they knew I couldn’t make the weight properly so I felt stitched up a bit, I felt bitter about the way my career went. I hated boxing. Then I had to come out of a brief retirement for Lennox! I knew I wasn’t going to win. I wasn’t in love with boxing anymore so I gave it a go and went through with it. I know I had a couple of great nights as well as that wonderful night in Stanley when it all came together. I was only 24 years of age, but if I’d have made any decent money I’d have retired there and then.”

Tyson Fury told me a similar thing after he defeated Wladimir Klitschko in November 2015. The then-heavyweight world Champion felt he had reached a peak that he would never reach again and ended up falling into the crevice of bad living that robbed him of almost three years of his career. McCrory was never a member of the in-crowd, which always makes it harder as you have to do so much more to get to where you want to be.

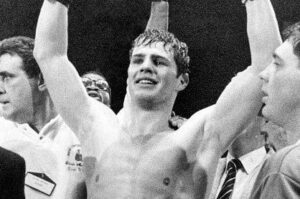

Despite winning the Commonwealth and British cruiserweight titles (W12 over Chisanda Mutti and Tee Jay in September 1987 and January 1988 respectively) plus his cruiserweight win and defence (W12 over Patrick Lumumba in June 1989 and W KO 11 over Siza Makathini in October of the same year), McCrory believes he was never given the chance some fighters are given to really have a true crack at maximising their ability.

“Very much so, the game is a very tough game,” he said. “I don’t know if it is easier now than it was back then because back then you had to be either with Mickey Duff or Frank Warren. Luckily, my good work with Tyson got Cedric Kushner on board and that got me the opportunity to fight for the world title. I knew as an Englishman, or should I say a Geordie, that he wouldn’t get me the money, but he would get me the opportunity.

“I made a good career with Sky after that yet as a fighter I’d thought if I forgot about the money and got the world title I’d make enough money to keep me for life. You know how long the feeling of elation stayed with me after I won it? Twenty-four hours. I had a dinner party made for me and I didn’t really talk, as it still hadn’t sunk in, so I went from the greatest feeling in my whole life to the worst feeling of my whole life. For the first time in my life I didn’t have a goal.

“I’d never been told to aim for a world title. Even my dad said to aim for British as no one from the North East had ever done the world title. I was told that my whole career. Then I win the world title, wake up the next morning and I’d done it. I’d never thought about defending it, winning another version or all of that — it had never crossed my mind. I never quite felt the same about competing after that ever again.

“That’s what happens to you. I was on the Dole before that world title win. I signed off the Dole after winning it, I was probably the only person to have done that. My post-fight speech was: ‘Stanley Dole Office, I’m never coming back.’ For me, the biggest thing was coming off the Dole. People think you win the world title and make a million pounds.

“I look at my career and think I had some good wins, some good nights, but I could have done so much more. When I was a pundit, I was sat with Manny Steward early doors and he said: ‘I’ve got to tell you one thing, my biggest disappointment is that I never got to train you’. Now, he probably said that everyone, but imagine what a difference that would have made. Imagine how different everything could have been? I went into a world title fight being helped by my amateur trainer, a lovely bloke who couldn’t even hold the pads. That what I had. Imagine training in Detroit with Steward? It is a million times better than working on one punch bag above a shop in Stanley.”

Despite those regrets, McCrory fondly recalls the night when he lifted the IBF belt in front of the people he knew and had grown up with. Stanley is a former colliery town that faded into high levels of unemployment once they stopped bringing that black gold up from the ground. You could get to the Leisure Centre fairly easily from any part of town. McCrory got there quicker than most as it was the end of the road that he lived on.

“It was magical,” he said. “I was 300 yards from home. I walked down the street to get to the venue. I’d been to see my wife and my little girl then was walking up the main street, as I lived at the bottom of the street and the venue was at the top of it, and I thought: ‘Jesus, why are all these people around?’ There were people in fancy dresses, flash cars, limos all that, so I was thinking: ‘What the hell is going on in Stanley?’ It turned out it was my fight. It was mad.”

A decision defeat to Alfred Cole away in Russia in July 1993 prompted McCrory to draw a line under his career. Luckily for him, Sky came calling and he established himself as a commentator and pundit who is still working the big fights and nights. However, there were rumours that he was close to making a bit of an informal comeback when Lee Froch, Carl Froch’s brother, had a go at him on Twitter.

Rumour has it that it prompted the two men to privately offer each other a straightener. It has become the stuff of legend, and not all legends are true in boxing, yet cooler heads prevailed and McCrory told me that the truth is far more simple and sedate. “Lee is great,” he said, still chuckling about the gossip and drama that built up around them. “Certain people you can push a little bit, have the bit of banter with and then the next time you see them you have a hug, I love Lee. Remember what this sport is about, one minute you are trying to rip someone’s head off and the next you are trying to give them a hug. This is the reality of the business we deal with. That is the sort of personality I am, one minute you can be as nice as anything, but if someone pushes you, you have to remember that I’m a fighter — I was born, bred and lived to do this.”

“Lee is great,” he said, still chuckling about the gossip and drama that built up around them. “Certain people you can push a little bit, have the bit of banter with and then the next time you see them you have a hug, I love Lee. Remember what this sport is about, one minute you are trying to rip someone’s head off and the next you are trying to give them a hug. This is the reality of the business we deal with. That is the sort of personality I am, one minute you can be as nice as anything, but if someone pushes you, you have to remember that I’m a fighter — I was born, bred and lived to do this.”

McCrory wasn’t too bad as a pundit, either. As we will come to see the second of this two-parter; he still retains his passion for calling fights. I hope we see a lot more of him after this lockdown.

Interview written by: Terry Dooley

Follow Terry on Twitter at: @Terryboxing