“You accomplish, you become successful and now your life’s gotta change. Ninety percent of boxers, if not more, have come from poverty. Nobody helps them out with anything. When we’re taking the punches, nobody takes them with us, nobody is running, nobody is starving to make weight with us.”

Since 1960, Youngstown, Ohio’s population had drastically declined following the ‘Black Monday’ collapse of their previously thriving steel economy. It left families struggling in low-income households and rendered an estimated 5,000 men and women unemployed, with sixty percent of the city’s residents seeking greener pastures elsewhere.

When looking through pictures of the tall, red-brick buildings and listening to Bruce Springsteen’s paining local tribute, it was hard to imagine happiness or elation in these parts. But even recently, they were united.

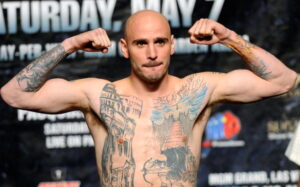

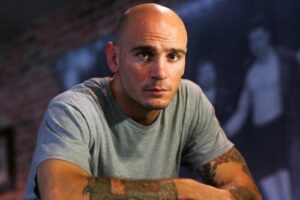

It was in this song you would find the strongest link to Youngstown’s last champion, the man who’d breathed hope into the sports bars and venues for the best part of a decade. The city that birthed the great Ray ‘Boom Boom’ Mancini had more recently given us unified, middleweight champion, Kelly Pavlik(40-2, 34KOs). Proud of his heritage and having repeatedly triumphed as their proud underdog, he’d paid the price by falling victim to incessant hearsay. Pavlik was the young, Slovak-Italian star who established himself on a global scale – yet never wanted to leave his people behind.

The purpose of Springsteen’s historical retelling was to emphasise the difficulties faced in the area after their industries were shut down. Its lyrics still ring true. The citizens that remain are fierce guardians of their own tarnished reputation – perhaps under qualified based on recent results, which indicate a rate of unoccupied housing at nearly twenty times the national average. Middle-aged locals were left searching for alternative employment, with bodies busted from manual labour and possessing limited skillsets.

It was a city full of fighters – it had to be – but it hadn’t fully returned itself to steady legs. One particular lyric stuck out, though, as The Boss explained a disloyalty that would later be experienced by our subject; “Once I made you rich enough / rich enough to forget my name”.

From a place where opportunity appeared sparse, Pavlik was held up on multiple occasions, by men wearing masks of friendship. The legendary Bert Sugar once said of Kelly, that he “has wrapped himself in the fabric of his city”. If he left Youngstown, those hard-working residents would claim The Ghost had ideas above his station. But by staying, he was constantly judged and scrutinised in the years after boxing had become his own steel mill.

“You know, when I retired, I was actually done at that point. Believe it or not, a lot of guys, they struggle with life after boxing. It’s not a longevity sport by any means. It really shouldn’t be, if you wanna stay healthy. For all of the rumours that were out there, the main reason I stepped away from boxing, about a year-and-a-half before I retired – I wanted to.”

He continued, “A lot of people are different. Some guys would like to fight until they’re fifty, but that wasn’t my cup of tea. When I turned pro I would joke around with my wife and say, ‘I’m gonna retire young!’ Towards the end, I just didn’t have it all the way inside my heart and I knew that boxing was a dangerous hobby to have if you’re not fully committed. Stepping away wasn’t that hard.”

“For me, that became the goal – to become a world champion and to make enough money to be financially secure. Even now, people think because I’m talking about making a comeback, I must be broke. No. I’m actually in talks with Dancing with the Stars, I have a manager who managed music icons like Michael Jackson. The offers are on the table. It’s not just boxing. There’s different types of things and I don’t have to fight.”

The mere mention of a comeback prompted twenty-one questions. Kelly had appeared on the enormously popular Joe Rogan Podcast (JRE) earlier this year, streamed by millions across the United States and further afield. On the show, he explained his sudden urge to return to boxing, six years after letting the dressing room door slam shut behind him.

Formerly a unified, middleweight world champion, his comeback was reportedly planned some forty pounds above his fighting prime – the cruiserweight division. Pavlik’s battles with Bernard Hopkins, Jermain Taylor and Sergio Martinez seemed distant memories, though he was still only thirty-seven years old. Just as suddenly as boxing had left his heart, some years later it had returned almost without warning.

“I really haven’t battled with the idea of it. I was just screwing around. I have a gym here. I was hitting the bag and I decided, ‘Why not?’ I’ve been doing good over the years. I’ve been busy and had my hands in a lot of different things. I’m kinda like an octopus! When I got on the Joe Rogan show, I was talking with my S+C coach, we actually cut back on power and did a bit more work on boxing.

“Nothing is telling me that it would be a good thing to come back. That’s kinda the issue. What I try to explain to people is that if you’re twenty-two years old and you take two years away from boxing, it’s not that hard to get it back. For me, being thirty-seven right now, I know it’s gonna be hard. But at the same time, I’m not forty. I’m not thirty-nine. Going back, that all depends on how I feel hitting the bag or on my first day of sparring… it’s all up in the air.”

The fact that nothing had been telling Pavlik to return to the ring seemed ominously familiar. In boxing, stepping away is often the hardest decision a fighter will have to make. Not the fighting; not the training; not coping with winning or losing on the big stage, but embracing the emptiness that follows. We’ve watched on through gaps in our fingers as fighters have announced comebacks or battled far past their best. The financial insecurity the sport affords its participants is often ignored, with former pound-for-pound superstar, Roy Jones Jr, even assuming Russian citizenship to continue his decaying career. They deserve better.

Before reaching the world stage all those years ago, the Youngstown fighter faced a notoriously tough Colombian. Edison Miranda, from Buenaventura, had never been knocked out, losing only once to former champion Arthur Abraham on the judges’ scorecards – yet Pavlik forced the submission of his South American foe in the seventh round. This was his arrival.

World titles came calling and he waited less than four months for his shot, a fight with unified world champion, Jermain Taylor. His profile boomed and his life would shortly be altered. Famed trainer, Emmanuel Steward who was in the corner with the defending champion from Little Rock, claimed the contest would be competitive for ‘about a round’ – he was almost right.

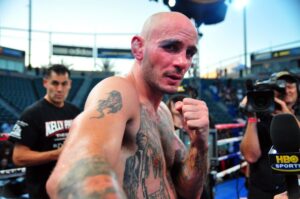

Entering the second round, Taylor catches Pavlik clean with the hope almost beaten out of him, dramatically touching the canvas under pressure from the skilled and savage champion. Somehow, when the fight appears to be reaching its premature conclusion, Pavlik scrambles to his feet, demonstrating his monstrous will to win. Bloodied and bruised, Kelly remains upright for the next twelve minutes, entering the seventh-round trailing by four points. The heart of Ohio starts beating, as he summons the strength to mount a vicious attack, leaving Taylor crumpled on the canvas. The stoppage appears from nowhere, an act of devastating sleight of hand. This is the historic victory that only a few could dream possible on a warm, October evening in Atlantic City.

He was the poster boy of Ohio following his initial victory and stunning second defeat of Jermain Taylor, draped quite literally in accomplishments, yet something was still missing. The depression that parts of his city experienced as a result of their depleted economy wasn’t lost on the now-wealthy fighter – despite what people thought, heard or whispered. The men who would darken the doors of their cheapest bars, discussing ‘old times’ and passing scathing remarks on their government were insignificant, but remained recognisable to the young Pavlik. They were bookmarks of an otherwise pleasant childhood.

“It was cool [growing up in Youngstown], I’m not gonna knock it. It’s a tough area. It was just one of them places you came up; you did your everyday thing to get by. I chose boxing. I’ve got a lot of people in Youngstown – which is really not the place that anybody has the right to come down on somebody – but for the petty things I became involved in, a lot of em’ turned their back. At the same time, I also had some of the most loyal fans, too. It was a hell of a support, so I’m not knocking everyone. There is a strong community and they back you through thick and thin. You won’t find any better fans – but you won’t find anyone as quick to turn on you, too, for no reason.

“There was a whole lotta’ things going on, but it was nothing in my personal life. My heart just wasn’t really in it. I had two young kids at the time. They’re still young, they’re only twelve and nine. It might have been that I was leaving and having to go to California during my career. For me, I wanted to be done. I was already a world champion, I already made money.

“From ’06-’08, I started to fall out of love with it. A lot of people go on to the [Bernard] Hopkins fight and say, ‘That ruined Kelly’, but I jumped up two weight classes to fight Hopkins. Then, I came back. That fight with Hopkins, it’s well-documented some of the things that were going on. Thomas Hauser, he was in the locker room, he seen it, but I never made any excuses because Bernard was a great fighter. My two losses, I lost to two Hall of Famers, you know?”

Tough fights kept coming and Pavlik became distant. His résumé speaks for itself, but throwing himself into training camps after capturing his titles became harder and harder. He’d tackled some of the middleweight division’s biggest names, beating plenty of top fighters and challenging one of the best of our generation, two weights above. But boxing was slipping away from him.

After returning to middleweight to defend his belts against both Marco Antonio Rubio and Miguel Angel Espino, he would suffer his second defeat when facing charged-up, Argentinian power-puncher, Sergio Maravilla Martinez. Beaten by a margin of four and five points on the scorecards, it wasn’t a shameful performance against a prime Martinez. It was the last fight Pavlik would lose, yet he never rediscovered that passion for the sport which had catapulted him towards fame and the end drew nearer with every punch thrown.

“I would say ’10-’11 was my lowest time”, he admitted “There was a lot of things that happened business-wise that I ended up taking the blame for. It was nothing to do with me, but I backed out of a fight in Youngstown because of it. I took the heat for it, I didn’t care. I would say that was a real gut-check when I wanted to walk away. Leaving my family for months at a time, I wanted it to be done, I truly did.”

“It wasn’t what everyone wants me to say. Like personal demons? Fuck that. I’m tired of hearing it. I’m not gonna throw any names out there but I could list 80% of boxers that do far worse than I’ve ever done. On a daily basis. Where I’m from, people do the same shit, if not worse – but they haven’t had accomplishments that put them in the spotlight. I was young. I sacrificed most of my life and I gave up having fun to become a world champion. Then, I conquered it and enjoyed living. Would I change it? Probably not.

“People say, ‘Well, you were out doing this…’ Hundreds and thousands of different rumours. I’m like the world’s most interesting man! The shit I hear, but what’s funny about it, the stuff I hear that I got in trouble for, most of those are false and wrong. I didn’t open my mouth because the more I argue, the longer it would be in the paper, you know? I always shut up. I never gave my side. I wanted it to be written and done, but that frustrates me because then I’m labelled as that.

“Maybe some of the fun I was having started catching up with me and maybe I started realising that, too. I wouldn’t say I had a short career, I had forty-two pro fights. That’s only eight fights less than Floyd Mayweather had. He turned pro four years earlier and fought four years longer! I was pro from 2000 to 2012, that’s not a short career.

I was middleweight champion for three years. Was there more I could have done? Maybe. Who knows? I know it would have been selfish for me to keep fighting when my heart wasn’t in it, but some of the public don’t give a shit. It would have been selfish to my family, but what good is money if I can’t count it when I’m fifty years old?”

His last sentence lingered eerily. The constant hunt for financial reward has led many down a dark path. What good is money, if you can’t hold it in your hands without your palms trembling? The time spent with his family would live longer in the memory than some of those early wins, gracing meaningless undercards, performing to a handful of drunken fans. Sometimes enough is enough.

The residents of Youngstown can’t help but gossip about the personal life of one of their most famous sons. He was forever flying the flag, representing their once-diminished city during his fighting prime, attempting to restore local pride. The people who used to chant his name now hissed under their breath for the sake of lousy rumour and speculation, growing arms and legs when spread from pillar-to-post.

“If you go back, everything was cool. ‘Kelly is just one of us. He don’t think he’s better than us’ and literally five months later, that’s when all the fucking rumours started happening. I go to the same place, people were like, ‘What is he doing here? He’s drinking, he’s drunk’ Most of the time I wasn’t. I had a couple of beers and it turned into a full-blown story. It’s frustrating. It’s like I’m damned if I do, damned if I don’t. If I’d moved out of Youngstown, I’d be too good or stuck up and snobby. I’d think I was better than everybody. But if I stayed there and did it, then I’m drunk and I’m a piece of trash.”

“I’m back on track. I’m working with sports now and I have two different businesses. I’m getting ready to open a gym in the summer and my podcast has taken off tremendously! Now, I’m clear-headed. It’s not realistic that I’m coming back, but if there was any time, it would be now. I’m considering it. A boxer is a boxer, you know? You’re a fighter your entire life and you’re always gonna have these little itches.”

Kelly contradicted himself when detailing life on both sides of the itch. His truths on the trappings of the sport should be an eye-opener to aspiring champions, preparing for the rise but never taking provisions for the inevitable decline. Now thirty-seven, the husband and father was pondering a return to the sport – on his terms. Could he come back to boxing at the top level? How many of those voices that used to bellow his name would accompany him on this journey, six years removed from his last fight?

Boxing had given Kelly Pavlik everything. From the streets of Youngstown, he had achieved at the pinnacle of the sport. When a hero’s welcome was expected in retirement, he looked cautiously over both shoulders, wondering who would sell the next story. The truth was, Pavlik had always been one of them, battling to represent them on a global stage, yet was scorned on his return, accused of forgetting his roots and often used for a quick buck. Despite it all, though, the former unified middleweight champion wanted to be remembered purely for entertainment.

“I just know from my fans and for the people who followed me and watched me fight, that I would fight my ass off for them. I’m not just saying that, I’m thankful for the support. My goal was to go in there and give the best performance I could. The point of the sport is to go out there and impress everybody, you want to perform when you have a crowd. That’s why you have twelve or thirteen thousand people watching.

“For a while, I fought everybody. I jumped up two weight-classes and fought an all-time great. Everybody talks about how old Hopkins was in that fight, but he went on to win the light-heavyweight title a few years later. What do I want them to say? I dunno. I never want them to say I was Hall of Fame or an all-time great, I just want them to think that I was an exciting fighter. I’m just realistic, that they enjoyed watching me fight.”

Interview written by: Craig Scott

Follow Craig on Twitter at: @craigscott209