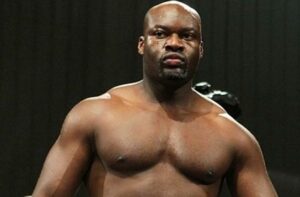

BOXING has a culture of vilifying people. As a collective we enjoy nothing more than dragging someone out of the chorus line and saying, to quote the film that all boxers love, “There goes the bad guy.” Former prisoner (he did five-years for armed robbery pre-boxing), boxer and now working actor Larry Olubamiwo (11-19, 9 KOs) was cast as the ultimate PED bad guy when he was popped for EPO, human-growth hormones, steroids and 10 other illegal substances.

This was after the Londoner lost to Sam Sexton by a fifth-round Technical Decision in January 2012. A four-year ban followed only for it to be slashed to a year when he passed on details of a Facebook discussion with fellow fighter Craig Windsor about steroid use to the UKAD, who banned Windsor and cut Olubamiwo’s sentence to a year as they offer a 75% reduction to fighters who serve up someone else.

The subsequent fallout robbed him of any goodwill he had gained as well as his interest in forging a career in the sport. He slipped into journeyman mode before sloping away from boxing in 2015 following a first-round loss to Hughie Fury. That was the last most of us heard from him, but a recent podcast interview with Richard Poxon raised the issues of his drugs use once again when he said that up to 80-90% of top fighters have used and abused performance enhancing drugs. Eddie Hearn issued a stern rebuke yet Olubamiwo is adamant that he was right to be so forthright.

However, more on that later. If you are tempted to skim read this until you get to that bit you will lose the sense of who Olubamiwo is. He has been portrayed as a bitter former fighter who is sounding off about boxing because he got caught out yet, as Boxing Social found out, there is more to the 41-year-old than meets the eye.

Our conversation took place in these strange, locked down, times. The lockdown has had an effect on him, as it has on us all, but the thing that struck him most, both on a personal and global level, has been the extent to which has shown the true colours of some companies that should be big enough to withstand the financial hit yet have furloughed staff and flung customers into the ether.

“I’ve got some savings, so that isn’t too bad, and the missus can work from home, but if it goes on it could become a precarious situation for us, as it is for other people,” he said. “It isn’t looking good at all. I’ve just had a call from a mate who said that the local housing association are chasing him down for rent. He’s a personal trainer who cannot work at the minute so why chase him down? This is a global situation.

“When this is sorted, people will remember the way certain companies and people behaved. It may be good for them financially in the short-term, but they are not thinking long-term and people will go elsewhere after this. The airlines are complaining about going broke, I had to pay £217 to change my ticket to get back to London from LA recently even though it had nothing to do with me. I know people have lost a lot more money.

“Airlines were charging customers to change tickets because they had to change flights. How are we to blame for that? People have paid thousands so I feel more for them — in the grand scheme of things my problems are small. I just don’t want to see airlines crying poverty because I just think: ‘Look at what you’ve been doing.’ Honestly, I don’t understand why these companies do this to their customers.”

Boxing has been hit hard. Top-level promoters and fighters are going to get through it as they will have earned enough money to weather the storm. The impact will be felt lower down the food chain: small hall promoters will suffer in the long-run, part-time boxers who work to fight might not be able to re-enter the fold — times tough, as the man said. How do people who rely on picking up bits and bobs of work adapt and survive in these unprecedented times?

“Acting, boxing — it is all part of the entertainment industry,” replied Olubamiwo. “People cannot work so there is that aspect to it. Even in the future people will be apprehensive about gathering in large groups after all this is done, so I don’t think shows will sell out as much as they used to, especially small hall shows, which would be a tragedy. The fighters on those shows rely on ticket sales so some fighters won’t be seen again.

“I feel sorry for boxers. Not so much the promoters, well not the big ones like the Hearns and Warren, who have money in the bank, but I feel for the smaller promoters and there will be fighters who cannot carry on after this as we don’t even know how long it will go on for. There are guys who are boxing full-time but only just about hanging in there. They have families to support through this so might have to take on jobs and then where do they find the time to train? I feel for them.

“When I was boxing everyone saw me on TV and thought I was a millionaire when nothing could be further from the truth. Same for actors, most are jobbing actors who aren’t getting paid millions, just like not all boxers get paid millions. You work fight to fight, job to job, and it is a tricky balancing act. If you have to quit you are quitting on your dreams, which is a heart-breaking situation to be in right now.”

Like boxers, many actors refer to what they do as a craft, something that requires hard work and dedication. Olubamiwo career stalled then reversed after he lost to Sexton so he hit the road, taking fights, and the money, as the away fighter simply to ensure that he could train full-time as an actor. He had been a contender until a single round reverse to John McDermott in January 2011. His loss to Sam Sexton came next. After that defeat and the failed test, the man some called “Big Larry O” became an opponent for hire. It stung in the early days.

“I think the Sexton fight was the turning point,” he said. “After McDermott I was written off. Before the test came out people said it was the best performance of my career. Plus how it ended, with the cut and him getting it for being up by a point, was hard. My thinking process at the time was that I did Prizefighter, and felt hard done by when losing to Jason Gavern (after a first-round knockdown in November 2011), and no opportunities were coming my way anymore.

“I was in drama school and wanted to concentrate on that. I had lost my passion for boxing, but didn’t want to work a nine-to-five so decided to go on the road and earn money that way. At first it is a little soul destroying, I have to say, as you are fighting guys that you know you could beat, and in some cases wipe the floor with them, but you know that if you do that the phone isn’t going to ring.”

“It is a weird position to be,” he recalled. “You heard journeymen talk about it in the past and don’t envision what they are saying. You think, ‘If you can think you can beat the guy go out and do it’, but you end up in that situation and think: ‘Ah, OK — I get it now.’ You realise that you won’t get those calls and won’t be able to pay those bills. I saw the bigger picture, though, as it was all about becoming a real, skilled, actor and that boxing was behind me at that point.

“I meet up with [former fighter] Gary Stretch in LA. I’d always wanted to act, but Gary told me it was like boxing and that you need to train to do it properly. I went to drama school for three-years and the rest is history. It helped solidify my skills as an actor to make the transition. I’m getting there. I’ve been cast in a few TV shows, a few films, and I’ve just done a massive Hollywood film that I can’t talk about yet. It was supposed to be out this year, but we have to wait and see now if it comes out this year or next. I’m waiting on it to catapult my career. It is just that we are all on hold right now.

“As a boxer you are there to entertain, to perform in front of a crowd, and you do a lot of interviews and that type of thing. I never get nervous going to auditions, as some actors do, because I’ve boxed in front of 10,000 people at the Echo Arena so I’m not afraid of going onstage in front of a crowd of people in a theatre. It doesn’t faze me. Boxing has been a big advantage for me going into acting.”

But it is the drugs, right? You are here for the drugs and the controversy rather than the story of someone who moved on from boxing and started afresh. However, Olubamiwo is more than happy to oblige when it comes to the seedier side of the sport and his perspective on it. After the drugs charge, he became the poster boy of getting popped for PEDs while other, bigger names served short bans and went straight back to business.

“I don’t know if I thought I was a scapegoat,” he said when asked if the fact he held his hands up and admitted to trying to gain the upper hand was the problem. “In hindsight, maybe. At the time I was wondering if I would get through it. Lots of fighters were doing what I was doing — it was an open secret — so I didn’t think it at the time. Now I’d make the argument that I was given the things that have come to light in recent years. Recent stuff with fighters has justified what I was saying about what goes in the sport in regards to doping.

“Well, maybe justified isn’t the right word, but I would say I’ve been redeemed because the stuff I knew to be true at the time is now being seen to be true. I basically wanted to remain competitive in the sport knowing a lot of boxers were doing the same thing — I felt I needed to do it. Some people will like me saying that, some people won’t, yet if I had to do it all over again I’d do the same thing — I’d just make sure I didn’t get caught this time. That might upset some people, but, again, I’m just being truthful here and showing people the reality of the sport.

“It (doping) is an issue in all sports. It is in boxing in particular because no one wants to acknowledge that it is widespread. Let’s get it right, boxing was one of the last sports to really involve doping testing. I am sure that a lot of the boxers from the seventies were at it. They weren’t testing for anabolic steroids in particular until the 1976 Olympics, where the testing wasn’t great, and those drugs were still legal at the time in America. Boxing people need to take a step back and look objectively at the situation.”

One case that has slipped by relatively unnoticed is that of Liam Cameron. The Sheffield-based boxer was done for recreation cocaine use and handed a four-year ban, one that effectively means his career is over. How do we square that situation with the fact that fighters like Saul Alvarez, who in fairness was caught under a different jurisdiction, served a six-month ban for two failed tests, which is the amount of time he takes out between fights? Cameron’s career is over. There is no consistency in boxing when it comes to this type of thing.

“I feel for Liam Cameron,” said Olubamiwo. “I don’t condone recreational drugs and don’t compare them to performance enhancers because, firstly, recreational drugs are illegal in this country, especially hard stuff like cocaine, and, secondly, it smashes up lives and isn’t in the same ballpark as performance enhancers. That being said, and from what I understand from Liam’s case, there wasn’t a lot of cocaine in his system.

“I feel that a lot of these rules of strict liability isn’t fair. They say it is in your system and they don’t care how it got there, but we’ve seen cases where there has been contamination yet people get banned under this strict liability rule. Anti-doping organisations need to fix up, basically. Someone like Liam Cameron gets banned for four-years while some pay-per-views stars get slapped on the wrist. They need to sort that out, how can that happen?

“I say what I say about pay-per-view fighters and how much of a percentage I think is doping then you get Eddie Hearn saying I’m talking rubbish. The same promoter who talks about me talking rubbish puts fighters who have failed tests on pay-per-view shows: Mariusz Wach, Lucas Browne, who failed two tests, [Alexander] Povetkin, also caught twice — do I really need to go on here? It smacks of hypocrisy and the facts back my argument up.”

It is hard to imagine what it is like for a fighter when a failed test comes in. Some fighters may have made a genuine mistake. Olubamiwo admits that he was trying to get ahead of the curve. Whatever the rights and wrongs, here in the UK you have to go through the opaque Kafkaesque process of dealing with the UKAD, who are, shall we say, inconsistent in how they go about their business. So how does it feel when you hear that you are going to be fighting a PED charge?

“My boxing career being effected did effect me somewhat,” he said. “I wondered if I would be able to pick up my career again. You get money worries. It was a hard time, but I don’t want any sympathy here as I brought it on myself. It was a time when I realised I could do what I really wanted to do, which is the acting.”

Many people in this boxing call for serious action when it comes to PED use, this writer included, yet the consequences seem to have a direct relation to how much water you draw within the sport. Drug cheats are a lightning rod — well, the ones who don’t try to slip out of it with an excuse — yet what about the other, legal ways that are used to get an advantage.

Gamesmanship is when you try to get an advantage through various means. Can anyone involved in boxing argue that it doesn’t take place? Is a champion training for four weeks before offering an opponent a fight they know they will have to take cheating or gaining a fair edge? Can we honestly say that a fight where someone weighs 10lbs more than their opponent on the night is a fair one? If the odds are stacked 80-20 in the favour of the house fighter, who has other advantages, is the contest fair and honest?

Once you factor in all the stuff that goes on in and around boxing you have to ask yourself if Olubamiwo, who fessed up, admitted his guilt and served his punishment, is really the bad guy or emblematic of a culture of ‘Win at any costs’ that leads to this type of thing?

“I am so glad you have said that, seriously,” he said when these questions were put to him. “I always get a bee in my bonnet when a few boxers say — and for a lack of a better word this pisses me right off — that it is going to take a death in the sport to sort this performance enhancing drugs things out. That makes it sound like there hasn’t been deaths in the sport already. Plus, are you trying to say that a death in the sport because of performance enhancing drugs use is more important than ones caused by other factors?

“Let us look at deaths in the sport of boxing. How many are because of what you just mentioned, guys not getting a lot of notice for fights so not preparing their bodies for going against a guy who is fully prepared? I am sure that has happened in boxing. Is anyone out there moaning or up in arms about that? No. The boxing industry needs to get a handle on that because performance enhancing drugs are not the problem per se — it is everything that goes with boxing. Boxing has had scenarios where a fit and ready fighter is fighting one who isn’t — that is a perfect storm. Don’t just jump on soundbites or bandwagons, which is just a way of life now anyway.

“I don’t like the hypocrisy. Certain promoters try to portray themselves as anti-doping advocates yet put fighters on shows who have tested positive twice. Again, the example is Povetkin. He gets done twice then gets [Anthony] Joshua and [David] Price then will probably still get [Dillian] Whyte on three massive shows. He got done not once but twice — twice! If you are an anti-doping advocate then how do you do that? Maybe give them a chance after the first one, fair enough, but how can you do it after two then put them in against your golden boy. It smacks of so much hypocrisy.

“This all came about because I did my interview on that show. Eddie said it was rubbish when I said about 80% of fighters had been on performance enhancing drugs. First off, why did he feel the need to say anything? Frank Warren puts on pay-per-view shows and didn’t say anything so, for me, it smacks of a guilty conscience. No one was referring to you specifically, so why get involved and then on top of that make a personal attack? The issue wasn’t addressed properly, I was called a bitter loser when I’ve now got a flourishing acting career. That’s why I hit him with both barrels. Just look at who he works with.”

And that was that. The softly and eloquently spoken former heavyweight prospect may be seen as a bad guy in some quarters yet he has moved on from boxing while boxing is still stuck in the mud when it comes to what constitutes a fair fight, and given its history of hypocrisy it always will be.

Interview by: Terry Dooley

Follow Terry on Twitter at: @Terryboxing