In recent years, the soaring success of young men from the traveller community, pursuing a career between the ropes, has continued to dominate boxing’s media. Our obsession with their culture, caravans and charisma has proven boundless, with Tyson Fury and Billy Joe Saunders capturing headlines for all of the right, and often wrong, reasons.

One young man attempting to force his way into British title contention has recently moved from his trailer, pitched on his grandad’s land, to a modern town house. For Lenny Fuller (6-0, 0KOs), the reason for his transition to fixed abode, blurted out during our conversation was plain, “It’s got central heating!”.

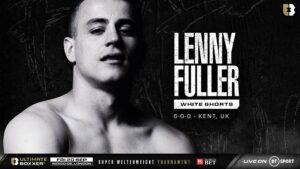

Currently undefeated in six bouts, the inexperienced welterweight is preparing to compete in the fourth installment of Ultimate Boxxer, set to be screened live on September 20th, on BT Sports. Through yawns shared on either side of the phone early that Saturday, we spoke about a youth spent battling elder siblings and the myth that fighting is a ‘must’ when growing up amongst young, traveller men.

“Nah, not at all. Me’ brother only had a couple of amateur fights. All me’ brothers have boxed, but nah, it was nothing to do with that. My boys now; one of em’ plays golf; one of em’ is a lazy shit and doesn’t wanna do nothing (laughs). There’s no pressure on us, at all. If anything, me’ ma’am would have liked us not to box. She’s always saying she can’t wait for me to give it up, but I won’t.”

Fuller continued, “Me’ uncle did a bit of boxing in his day, but me’ dad, he never boxed. He’s five-foot-nothing, as round as a… Well, he’s never boxed. Mum’s side haven’t really boxed, either. The first amateur gym I went to, the trainer said to me that he loved working with traveller boys because they never shy away. They don’t have to be asked twice to spar. They never forget a gumshield. They’re always ready to go and they want to fight. It is in you, a little bit.”

“You gotta understand, I had three brothers, so you can imagine that was a fucking headache of a household for anyone! Constantly fighting, always putting gloves on and sparring. You’d have a rough time if you couldn’t fight in that house.

“We did [live in a trailer], but I’ve got two kids. I lived in there until I was about seventeen. That’s when I met my wife, but only recently I’ve moved back into the house and that’s mainly to do with training. I’ve lived in trailers all me’ life until the last year or so. It’s just better with the kids. It’s right next to their school and I just like it a bit better.”

The next edition of the knockout tournament would be staged at the weight above Lenny’s natural division, but when finding out a little more about the Maidstone boxer, it was clear those seven pounds held little importance.

He’d joined the gym initially as a young boy, taking up boxing to learn how to handle himself, dipping in-and-out, without direction. After falling out of love with boxing during those testing, teenage years, Fuller returned, eventually signing up for unlicensed bouts and challenging ex-professionals, often emerging victorious.

The unlicensed scene here in Britain is regularly the subject of concern from an ardent boxing community, especially surrounding their medical provisions, however Lenny explained that it was an inability to progress that saw him switch to the professional game. When preparing for UB4, however, those shorter bouts would be key, revisiting three-round sprints with a focus on first impressions.

“I actually really enjoyed the unlicensed stuff”, he admitted. “It’s not far away from the pros – not the level and stuff, or the training, because it’s only 3x 2mins, but there’s an appeal to anyone. I built most of my following up from the unlicensed [boxing].”

“It wasn’t far from where I’m from, in Maidstone. You walk out to lights and music and some of these small hall shows ain’t much more exciting than the unlicensed shows. I boxed quite a lot of ex-pros. They were half decent, but they just couldn’t sell tickets, so they dropped back down to unlicensed.”

“Things are run a lot better [in professional boxing]. It’s a lot safer with the yearly head scans and the medicals. I’ve always said I’ll box at any weight. Whenever I could box, I would have boxed, but I could see my future in professional boxing. There was no set future in the unlicensed stuff, for me.”

The future that Fuller refers to could be a few steps closer if he performs on his biggest stage, to date. Confidence wasn’t an issue, that much was evident, but it was an emphasis on adaptability that struck me.

He constantly spoke about switching his style to match an opponent, whether it was throwing bombs in the pocket or fluidly picking points on the outside. Lenny was convinced he could nullify the strengths of his potential opponents. Alongside him, lining up in a battle for the Golden Robe, were a peculiar mixture of domestic prospects.

In Sean Robinson and Joshua Ejakpovi, you have two men who’ve recently battled for the vacant Southern Area title, with Goodwin Boxing’s Robinson emerging the victor. Steven Donnelly enters the contest as Ultimate Boxxer’s first ever Olympian, representing Ireland in Rio just over three years ago. Despite feeling comfortable whoever he faces, there was another unheralded entrant that Fuller reckoned could spring an upset.

“I done a little bit of research [on the other boys]. Lewis Syrett is only from up the road. I’ve sparred a lot of boys that have sparred him.”

“Steven Donnelly, everybody keeps banging on about him! Because he was an Olympian? He didn’t medal, did he? Is he from Southern Ireland? He’s not a great standard for being an Olympian, I don’t think. He boxed Kevin McCauley and made it hard work. I wouldn’t mind getting him [Donnelly] in the draw, first. I’d feel confident.

“[Joshua] Ejakpovi is definitely one to watch. His hands are quite slow, though. [Kingsley] Egbunike, something like that. He’s probably the danger to watch because nobody has really mentioned him.”

The twenty-five year old family man was now able to focus on boxing full-time, thanks to a recent sponsorship package, freeing up time spent formerly as a personal trainer. Battling names such as Donnelly and Robinson required as much preparation as possible, something Fuller was thankful for.

Boxing has started to feel like a career for Lenny since the beginning of 2019, with manager Joe Elfidh guiding his career, laying Ultimate Boxxer on his lap. Despite the weight disparity, the pair’s plan was to take every opportunity with both hands, carving out titles and television time as they progress.

Coming home to his well-heated residence, comfortable with his wife and two sons loyally supporting him, the stage was set for Lenny Fuller. Drifting from travelling teenager to successful professional, he was ready to fight anyone – though, in truth, he always had been. It was ‘in him’, as he bluntly put it. Beating three men in one night would signal success on September 20th, something ‘The Main Man’ was relishing.

“[In twelve months], English title, British title. I don’t know. Preparing to drive my Lamborghini. I’ve spent a lot of time saying how good I can be… (laughs). There’s not a lot I can’t do. I ain’t saying I can’t do everything fucking excellent, but in this camp I am just trying to be the best me.”

“The hardest part is finding time for my family. If you’re boxing, you’re always at boxing shows, training or out meeting people. You gotta try and sell yourself, because you’re a commodity, ain’t ya?

“That’s [all] I’d like people to think – that I never avoided anyone. I’d have fought anyone. If there’s a shot, we will take it, definitely. I feel confident enough. My fitness will never let me down. But I’m still learning on the job, I know that.”

Interview written by: Craig Scott

Follow Craig on Twitter at: @craigscott209