The sun shining over both Chelmsley Wood’s rough council estate in Birmingham, England and the glossy city of Calabasas, Los Angeles is shared. Its intensity varies, burning brighter on American soil as it bounces off the windows of glamorous, designer shopping malls. Hollywood sits gently in its distance, the home of the beautiful, often painting over their painful pasts with smiles and surgery. Life isn’t quite what it seems.

Boxing has found a home in LA, with Freddie Roach nurturing his stable of elite-level fighters at the Wild Card gym on Vine Street. It would be easy to pluck names from the sport’s hat, praising those who’ve emerged from lives of poverty or travelled thousands of miles empty-handed, etching their names into boxing folklore. This story was a little different, though.

This time, it wasn’t a fighter on the other end of the phone; it wasn’t a coach or a promoter. The softly-spoken, barely-British accent telling stories on this Thursday morning belonged to a woman more commonly appreciated for work behind the scenes, yet never justly credited for her contribution to an unforgiving business.

The remarkable story of Rachel Charles caught me off guard; including all-consuming poverty, child abuse, becoming a teen mom and her chance meeting with a man named James Toney. But it started as an outcast in the Midlands – the only mixed race child in a brood of four.

“My sisters and I shared a room,” opened Charles, reminiscing about her childhood blueprint – conjuring buried, bittersweet memories.

“My brother had his own room. My mother bred dogs, so we had a shit load of dogs. It was always busy, every single day there was something going on. It was a town house in a council estate; kitchen and all that on the bottom, living room in the middle. It was pretty interesting little neighborhood.

“Now, I live in The Valley. I live in Woodland Hills. If I was to look out my window right now they’re actually building a hotel on the corner of my block. I live in a brand new building and it boasts a rooftop garden area with barbecues and pool, all the bells and whistles. I’m not far from Calabasas which is quite a famous neighborhood. It’s just really pretty, it’s really nice where I live.”

“I’ve lived within five miles of my original home for the past 30 years. So, this is my hood, you know? A lot of Hollywood folk live around here. A lot of athletes. Especially over in Calabasas – so that’s Kardashian country right there. It’s pretty fancy, lots of nice places to shop. Jimmy Choo, Dior, you know?”

Self-styled ‘Pitch Ink’ for her expertise in slinging promotional material at outlets for her fighters, her transition from the gutter to gazing at the stars was admirable. It wasn’t easy, though. Now, travelling to Las Vegas and back for promotional work is just part of her day job, running herself into the ground for the Sheer Sports’ stable.

However, Rachel’s affinity with boxing started before she’d even attended a fight or moved Stateside. The heart and determination required to battle life’s hard knocks had given the young Brummie an education, though too much, too soon. That smile painted on for journalists or young, aspiring champions in the gyms she visits, serves to fend off any probing questions.

“So, I think I was around about five when they told me that I had a different dad,” Charles explained, candidly, “At five everything changed for me parent-wise, and identity-wise. Then at ten, I’m gonna… I’ll tell you, I was molested, which, well that was it. My whole life before that was just gone, I don’t even really have any recollections of anything before that, not even the day before that happened.”

“I saw my own dad for the very first time at the movie theatre. My mom took me to the movies, to the cinema, to see my dad in a movie. So, that’s how I first laid eyes on my biological dad. He was in a movie, it’s called New York, New York with Robert De Niro and Liza Minnelli. I knew my dad was a drummer for Stevie Wonder and the whole bit. So, I got free lunch at school on that forever. I played that one up.”

With her only child, daughter Georgia, born when she was just seventeen and with a council flat to live in, becoming trapped in Birmingham seemed inevitable. Charles escaped violent boyfriends during that period – including one who stabbed her in the face. It was her against the world, until it threw her a twist of fate one evening at a Neil Diamond concert.

The brains behind adopted British boxing anthem, ‘Sweet Caroline’, Diamond’s percussionist was the mature American, Vince Charles. Handsome, slick and based mainly in the States, he pointed his drumstick symbolically at Rachel from the stage and cast a spell on the young romantic. The pair would become engaged, get married and set up shop in Los Angeles. She had nothing to lose and, on reflection, probably owed money to her landlord at her time of disappearance.

“This is a legit story; I picked up my social on the Monday, so you had to sign the book. I signed the entire book over to my mother because I knew I wasn’t coming back. I signed the book over, right up to the last page. I had an electric meter, you know you put the 50p in, turn the dial and you get electric? I cracked [open] the meter, ran down the road with a black box full of 50p pieces. Went up town and bought a few clothes because I had none!

“I came to America on the Wednesday. I pulled up to Vince’s house, he had a four-bedroom house with a swimming pool. So, I was like, I’d just robbed my electric meter, and now I’m standing in Los Angeles and there’s a swimming pool in the back garden. How the hell did this happen?”

Her move to the United States was by chance, as was her introduction to boxing as a sport. The management and marketing of fighters, though, seemed to come naturally. It was at the conclusion of Charles’ marriage to Vince that she started to consider her next career move. What was she good at? What could she offer?

Stranded overseas, thousands of miles from her mother and the unnerving comfort of the breadline, Rachel knew that bouncing back was the only option. Focusing on her strengths, she began networking. She couldn’t sit scanning items at a checkout – she had more to offer. The unemployed, single parent was a role she was familiar with, but it couldn’t last for the expat.

“Growing up, I knew a few boxers, a few local guys. Then I was here, obviously muddling through, and a friend of mine was friends with James Toney. So, she had said to me one day, ‘Come and meet this guy I’m talking to. I think you’ll like him, he’s fun.’ So I went, I didn’t know who James Toney was, I didn’t know a thing about him. And we hit it off instantly. I mean he was the most vulgar person I’ve ever met. Vulgar isn’t even the word, there’s no word for him, he’s fowl. But I fell in love.”

“He took me to Dan Goossen. He goes, ‘You’ve got to come and meet my promoter.’ So, I was like, ‘Okay.’ He took me to meet Dan Goossen. I didn’t have a job, so I was actually homeless, I really fell on hard times. I was homeless at the time, and jobless, penniless, the whole bit. And Dan Goossen offered me a job to answer the phones because he liked my accent. So, I did that. And James was like, “Just stick with it, it’s going to be something for you, I know it is!'”

Thankfully, it was.

Boxing, the commercially insecure sport, had become Rachel’s life. Her obsession with its characters and back stories had fuelled her fire. James Toney wasn’t a bad place to start, but who was next? Working for Dan Goossen was incredible for the makeshift public relations guru, winning or learning with some of boxing’s biggest prospects and stars.

Now working alongside unbeaten, Irish twins, Aaron and Stevie McKenna, she was energised daily by their pranks and use of Photoshop or similar apps. It kept her young and kept her fit after recent surgeries. When Charles had dipped her toe into boxing’s shallow pool of non-fighters, her existence as a confident woman caused a stir. The sport’s hierarchy were creatures of habit, but she followed in the footsteps of one of her icons – breaking the mould.

“Jackie Kallen is just the be all and end all,” stated the adopted American, “She’s everything. She’s just the best, for sure. But there was also a PR lady that worked for Neil Diamond and I was like, ‘Hmm.’ And that’s how I started doing what I was doing for my husband. But in boxing it’s Jackie Kallen, there’s just no question. I didn’t know who she was. I’d seen that movie Behind the Ropes or whatever it’s called.”

“That was before my boxing days. Then I remember meeting her. I met her at Foxwoods, and it was James Toney, and I forget who he was fighting. Anyway, it was forever ago. So, I met Jackie, and I literally had a full on, ‘Oh, my God, that’s Jackie Kallen.’ And I went over, and I was like ‘If there was no you, there’d be definitely no me.’ And I’ll never forget it. We had lunch that week when we both got back to LA. She gave me a pair of earrings, these long, beautiful earrings. Jackie Kallen reminds me of Stevie Nicks.”

With Kallen’s backing and her own, unrelenting determination, Charles established herself as one of the most effective communicators in boxing. Column inches, website coverage and social media management has been balanced beautifully, with her stable growing consistently. For Rachel, it was about the unfathomable stories, and the fighters who would have been swept under the carpet without her. She viewed boxing from a storyteller’s vantage point, selling hope and pushing dreams on paper.

She was thrown into boxing’s deep end, sneaking between the ropes for some of the most anticipated contests in recent years. The pressure bothered Chelmsley Wood’s fighter, but it never showed. From the busted electricity meter, short on cash, she’d moved into a world overrun with dirty money. For Charles, it was about the people, not the pound notes, and she has worked with some of the best.

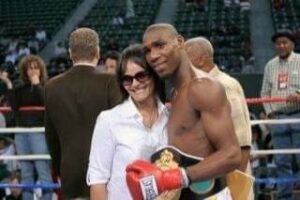

“Before I knew it I was working with Glen Johnson. My first fight was Glen Johnson versus Antonio Tarver at the Staple Center. Then I did James Toney’s World Championship fight in Madison Square Garden. And there I was standing in the middle of the ring. James is in the winning corner crying, I’m in the neutral corner crying. We’re both crying for different frigging reasons! Obviously I’m crying because I’m like, ‘Holy shit, I made it.'”

“Boxing’s full of people like me. There’s no question. I mean to look at me… It takes one to know one, right? So, when I’m talking to someone I can pick up on little things that they say, or if I have a gut feeling or kind of move around a subject and see how they respond, and then it would confirm what I thought I knew. To look at me, you wouldn’t think that I’ve gone through half the shit that I’ve gone through. But I do feel like I can talk to these kids, I feel like I want to look out for them, I speak their language. And it’s worked. I mean by speaking their language, I’ve gone through it.

“My dad’s a lousy piece of shit, I mean he really is. And a lot of these kids have not had good relationships. I was a single mom, so I’ve got that. And I can talk to all these lads. I just feel like I want to look out for them. I just feel like no one looked out for me, so I’m like, ‘All right, let me look out for these guys.’ And no-one asked me. But I just feel like it’s this gut calling in life.”

That feeling, the pang in your stomach and lingering sense of purpose doesn’t bless everybody. Rachel Charles didn’t have it when she worked in Birmingham, part-time. She never had it sitting at home, approving of songs and percussion arrangement. It was boxing, in all its brutality, that allowed the Brummie to finally settle. She knew, even then, that the fighting left her ambivalent.

It didn’t matter whether it was combat; fist-on-fist. It could have been battling mental health or struggling through doubt, ‘Pitch Ink’ was there. As we closed our conversation, she cried. She gave me a pat on the back when I’d made Buddy McGirt shed tears, happy with the content months prior. But this was different.

A woman lifting the lid, opening up on sexual abuse, domestic abuse and luck was striking, especially given it was the first time. She has a smile that starts in the Midlands and finishes in Los Angeles. Rachel Charles is one of the most honest and genuine people I’ve encountered in boxing – she has been consistently for three years. Boxing, or fighting, was in her blood. Fending off her knived partner or stealing money in the scheme, she survived.

The sun shines brighter in LA, undeniably. It’s a something to do with the equator, or climate change, right? Charles acts as its conductor, spreading positivity in the face of often-heinous adversity. She is more than capable and overly-qualified.

“Boxing’s draining. I mean a fight week will just smash the spirit right out of you, because you’ve got to deal with so much. I think that I’m a crier anyway, I’ll cry at a commercial. So, I am an emotional person anyway. But I mean, say if we’ve had a loss or something, and I’m just like, ‘All right. You know what? You live to fight another day. It wasn’t your night.’

“The biggest struggle for me is my personal demons, from what I went through as a kid, kind of everything falling apart, being homeless. I overcame all of that, still raised my daughter, she’s very successful now. How do I get rid of them without the help of a prescription medication or a bottle of alcohol? I’ve never touched those tings, so, yeah, I mean I think my biggest thing is just my own personal shit. I’m pissed off [about that].

“So, I think that’s the biggest thing that I’ve had to overcome, just that dark cloud over my head constantly. ‘You’re not going to be anything. You’re not going to amount to anything. You’re going to be…’ They put you in those brackets. ‘Okay, you’ve gone through this, and now this is going to be your life’s path because you’re a victim of whatever or whatever.’ And I’m not a victim. I’m a survivor!”

Rachel is a survivor. She’s loyal and fierce, with reason. Boxing has an affinity with her story, because, subconsciously she’s had to battle for peace. I asked her whether boxing and Rachel Charles were always destined to become entwined?

She had recently suffered the loss of former favourite, Eloy Perez. She’d watched Paul Williams struggle for relevance, stuck cruelly to the bottom of his wheelchair. This was her sport. This was her livelihood. Despite the trials and tribulations, Charles was integral to the success of boxers like Adam Lopez and Jason Quigley. She knew her place.

“It’s a big year for me. But I figure, you know what? I’m just going to stay until boxing doesn’t want me anymore. I mean I would say that, because boxing will get rid of you when it’s done with you.”

Interview written by: Craig Scott

Follow Craig on Twitter at: @craigscott209