The phone rings out, unanswered for a second time. Nothing. Fighters aren’t known for their timekeeping or their reliability, but when packing up, resigned to try my luck another day, an incoming call then flashes across the screen. The voice of former WBC Super bantamweight challenger, Rendall Munroe(28-5, 11 KOs), greets me, barely able to contain his excitement at the thought of talking boxing.

“I didn’t even know you had called me,” he told Boxing Social. “I’ve got this dodgy phone where sometimes it’ll ring and then sometimes…,” he trailed off for a moment before picking right back up. “Like I said, it just text me now saying I’ve had a missed call, but the phone didn’t even ring.”

I told Rendall that in some cases that type of phone is a blessing, depending on the caller.

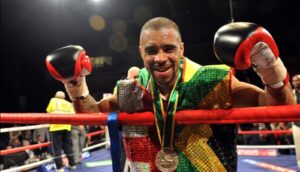

It is almost 10-years since Leicester’s ‘Boxing Binman’ travelled to Tokyo to challenge for the world title on the crest of a wave after shocking future world champion Kiko Martinez in a pair of contests that stamped his authority on one of boxing’s shallow divisions. Munroe was crowned European champion in March 2008 when nobody outside of the East Midlands had given him a chance of beating the Spaniard, but he soon found out that fighting at the upper echelons of an already slippery sport didn’t pay dividends.

I caught up with Rendall a couple of weeks after he’d officially been given his trainer’s license by the BBBoC. Still training regularly, working with troubled teens and juggling with the idea of another comeback, the British-Jamaican had plenty to get off of his chest.

“I’m telling ya’, people will still ring up the Shinfield gym now to see if I’m in there for sparring,” explained the evergreen Munroe. “I think for me, one of the things what always stopped me from getting a trainer’s license before was I always thought that they’d make me stop sparring and things like that.

“That was one of the reasons why I was always like, ‘I ain’t ready to do it yet,’ because I still loved doing my own thing. When I went for the interview — because obviously you have to go first before you do all your courses — the first thing I said to them was that if I do take my license, I might still have a spar now and then. They were like: ‘Well, Rendall, you still look like you’re in shape, so we don’t see a problem with that.’

“That was the green light for me, to be fair. Alright, I’m nearly 40 this year but a lot of lads who have been in there and are still in there training, they’re like: ‘Rendall, you’re still a monster. You’re still good enough to be fighting.’ But the thing for me is that I was lucky. Being in the game and knowing the way the politics of the game worked, the truth be known, I’m good enough to be in there and I’m good enough to do my bit but how am I going to get a fair crack? I just don’t think I will.”

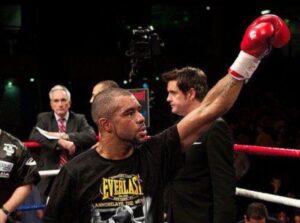

Whether or not Munroe could hang with the new generation was a lengthy topic for another day. Boxing had been his grounding and also his saviour at times, escaping trouble on the streets and allowing him the chance to exceed expectation. Nobody fancied Rendall Munroe as a boxer, with an underwhelming amateur career and the assumption he’d spend life in the away corner, slipping shots for spending money.

He detailed life in Leicester, the product of mixed race parents, learning the importance of being studious from his disciplinarian father. Munroe explained: “He was very strict about school, coming from the Caribbean without much of an education. So I used to get the, ‘Rendall, you’ve got to do this, Rendall, you’ve got to do that’, type-thing and I just hated school. I didn’t lie to anyone.

“I hated school and I got into boxing because one night I had just come home from school and I was like, ‘I’m going out.’ My mum was like: ‘When your dad comes home from work, you’re in trouble.’ I thought: ‘Right, my uncle owns a boxing gym down the road so I’m going to pretend I want to be a boxer for a few weeks, I’ll go down there.’”

He spoke about this time in his life with boundless energy, something he still cannot shake. “I was just always full of energy, really. I just couldn’t sit down. I was always up to no good. Growing up, you start to put yourself in a few places where you shouldn’t, but I kind of knew there was a line you couldn’t cross. So when things started to get a bit hot, it was like: ‘Whoa, take a step back, Rendall. You’re not really about that. You’re tangling yourself up where you don’t need to be.’ I just stuck to my boxing.”

After dropping a decision to Andy Morris for the British featherweight title in 2006, the people’s champion wearing his high-visibility binman’s vest bounced back. Wisely dropping down a division then marching towards his shot at the English belt, he defeated Marc Callaghan via sixth-round retirement win in that one.

Little did he know that a surprise fight with reigning European champion Kiko Martinez would await him, one that he won by majority decision. Rendall told me of his frustration, beating various boxers who’d go on to capture their own world titles whilst he watched on after a series of unfavourable fights. Martinez was one of those, with the Leicester-man beating him twice fairly and squarely. Munroe looked like every inch the low-budget challenger on those nights in Nottingham and Barnsley yet he fought for pride, emerging as European champion against all odds.

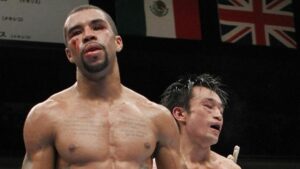

Munroe toppled former Mexican world champion Victor Terrazas [w rsf 9 in April 2010] before traveling to Tokyo, having already considerably over-achieved. Losing to long-time WBC champion Toshiaki Nishioka by decision held no shame and proved a step too far, but the East Midlands-fighter left no stone unturned.

“I ate right — I did everything right that night,” Munroe admitted. “I would usually say, ‘If I don’t win, it’s the man upstairs — it ain’t my time,’ and I think that’s the way I looked at it in Japan. But I thought, you know what, I’ve proved myself good enough to be up there with the best. I always remember Mike Shinfield said to me on the flight home: ‘You know what, Rendall? You’ve just proved you’re too good for your own good.’ I was thinking: ‘What do you mean by that?’ But then you start to realise what he meant. Nobody wants to fight you. So, why am I really fighting?”

Battles fought between the ropes were effectively over for Rendall on his return from Tokyo, despite comeback attempts when facing future world champions Scott Quigg [L rsf 6], Lee Selby [L rsf 6] and Josh Warrington [L rtd 7]. He was dragging himself out of the away corner in unfavourable circumstances, selling his name and reputation but never disgracing himself. When the phone started ringing in those days, it was more often for favours than opportunities. He ranted and raved about his fight with Scott Quigg in particular, adamant he would have beaten the Bury-man if he had been allowed to continue. Alas, he was stopped and the record reads Quigg by TKO. It just wasn’t to be.

Rendall’s last fight was six years ago and boxing has been living rent free in his head ever since. The former binman hoped to return to his old job, claiming he loved the idea of working on the bins between fights, but he was turned away after being told he had become difficult to work with and was displaying a bad attitude, claims that Munroe strongly denies. He gave weightlifting a bash, trying to use his natural athleticism and dedication to sporting endeavours yet it never stuck. He started hosting personal training sessions, as many former athletes do, working from a smaller gym to begin with, before seeking a larger facility due to popular demand.

Opening up on the emptiness that follows retirement from boxing, he continued: “People always say, ‘Don’t put all of your eggs into one basket,’ don’t they? I think I did do that. I think when I was away from work and I wasn’t training, I got kind of lost. What am I going to do now? I’ve got no work. I’ve got no boxing. I used to find myself coming in and sitting in the gym at three, four o’clock in the morning. (I was) just sitting there. At the time, you don’t realise that you’re doing that. I end up just putting some music on and sitting there — doing nothing.”

Ensconced in the nothing that follows a career of performing under pressure, the clock began moving in slow motion. He didn’t have his high-vis jacket or the camaraderie of the bin lorries anymore. Strangely enough, his next career move would come where many would have least expected it — education. The kids he is working with now remind him of a younger Rendall; confused or mixed up, bowing to the whisper of the streets. He started working with troubled teens after spending time visiting local schools, flashing trinkets and talking about that trip to Tokyo. Beneath the surface, school was an environment he’d never felt comfortable in, excluding Physical Education, of course.

“I used to go to a lot of schools doing talks about my background, where I’ve come from and how things changed for me through boxing,” he said. “I started talking to a guy, Graham Chambers, about what I’d love to do, building up my own school, like an alternative way of doing things. We decided to open up Triple Skills, which now works with kids who’ve been excluded from mainstream school. It is excellent. I’m trying to help them get themselves back on the right road, in the right way.

“When I was a youngster, you would look at the teacher in attendance like: ‘What can you tell me? You don’t know nothing about me.’ These kids now, they look at me and they know that Rendall’s been there. When it comes to the street talking, I know it all. You get a little bit more respect from that. I play the lottery every week because I want to win it and build my own school. I believe there’s certain things in schools that ain’t working for kids of this generation and I’ve got plans.”

He’s come a long way from the Shinfield family gym, normally flanked by manager Mike and long-time trainer Jason, who helped him navigate his career, both stone-faced and dealing in loyalty. The flags that draped from the low-hanging ceiling of their gym were from a mixture of countries and football teams with words splashed across them declaring support for fighters. It was the perfect setting for Rendall. No frills and no complaints. He stuck to boxing with the faultless dedication that he now intends on transferring into his other ventures. It didn’t always go to plan between the ropes, but both then and now, he surrounded himself with good, honest people.

I’d recently watched him share pictures and videos of him and his daughter cooking Caribbean food, pouring time and love into those he’d spent long spells away from during his prizefighting career. Munroe hadn’t managed to capitalise at the top of boxing’s mountain, but he gave it everything he had, retiring as a former English, Commonwealth and European champion. He told me he wanted to be remembered as “a down-to-earth guy who loved everything about the sport and believed in himself.”

“I want school kids to learn about a trade,” he added, the passion clear to hear in his voice. “So that when you’re finishing school, you can either work somewhere straight away or you can set up your own business, because you’ve got that plan. I got to touch my dream. I want someone to hold their dream. I didn’t get to hold mine, it was gone. But if I can get someone there, then what more could I want?”

That gimmick, ‘The Boxing Binman’, had made for good copy in local newspapers and sports websites, telling of his ‘rags to riches’ success. He wanted to pay it forward, allowing troubled teens the second chances that he was often denied during his own career. Now, almost 40-years old and just about loosening his grip on the idea of boxing again, Rendall’s passion once again had become cleaning up the streets of Leicester.

Interview written by: Craig Scott

Follow Craig on Twitter at: @craigscott209