Cycling through all four of Hartlepool’s seasons in one day, the young daughter of a foster carer and a roofer found familiarity in Hartlepool’s fully-funded Headland boxing gym. Occupying her evenings after school and filling time on the weekends, she devoted herself to the sport, when others crumbled at the door of teenage vices.

The wind and lashing rain that danced up from the tyres of her bicycle or attacked the Town Wall at the docks was pretty normal. It wasn’t glamorous, growing up in her little corner of County Durham. It certainly wasn’t Las Vegas. But it was home, with its marina and historic tall ships.

Hartlepool, just a modest seaside town situated in England’s North East, has suffered. After recent, governmental funding cuts, it was left trailing its peers for spending-per-household as recently as 2014; with an alarming 30% of homes statistically ‘out of work’ only two years ago. Succeeding seemed hard enough, let alone with a splitting smile on your face.

“It is quite a working class town, Hartlepool, I’m from quite a rough estate,” explained its unbeaten, leading lady, Savannah Marshall (8-0, 6KOs). She spoke to Boxing Social only a couple of weeks from her maiden World title tilt, featuring on Matchroom Boxing’s April 4th card.

“We were always out [on the street]. I used to come back from school at like four o’clock and you’d be in for eight – that type of thing. My mum is one of seven daughters and my dad’s one of seven, as well. Both sides are very, very big and loud – totally nothing like me. And my brother and my sister are quite loud as well.

“I think growing up, I was always the shy, timid one and I remember people would always say, ‘I can’t believe that Christine and John Marshall are her mum and dad and she’s that quiet!’ My mum and dad always looked after me, my brother and my sister, but we were never given anything. Everything had to be earned.

“The boxing club that I started at, they never charged [money] or anything like that, which was good for me. And it was quite far away, so I cycled from the age of 12 until 17. Four nights-a-week, I used to pedal there, pedal back in the wind, rain, cold, whatever – until I drove. And I absolutely loved it. I never missed a session.

“After a while, it just becomes a way of life. My first amateur coach, Tim Coulter, he gave me a key to the gym. So even on my days off, I used to run to the gym, do some training and then run back. I think that’s when I really started to come into my own. My amateur coach was all about technique. So I think, looking back now, them little extra sessions that I used to do on my own was what really set me in good stead.”

Through boxing, ‘The Silent Assassin’ soon travelled the world and now, as a professional fighter, she has the chance to conquer it. After becoming the first British, amateur female to capture a World Championship gold medal eight years ago, Savannah now owns an entire set of the tournament’s podium positions. They sit, pride of place with her Commonwealth gold and European bronze medals, capping an unbelievably successful career in the national singlet.

It’s been a long, hard slog for the 28-year old who admitted previously flirting with retirement. Now training with the astute Peter Fury, she spoke of her own humble beginning and the importance of patience for punchers. Emerging from a working class town, she was never blessed with endorsements or sponsorship, though Marshall’s talent became difficult to ignore.

Shouldering the weight of the town’s recent sporting hopes, she would quietly enter into the world’s most prestigious, amateur boxing tournament as the favourite. She was ranked World number one entering 2012 Olympic Games, had already defeated her nearest rival and should have been selecting outfits for potential open-top bus parades. But it just wasn’t to be on that occasion, or when faced with similar circumstances four years later.

“I was beaten a long time before the Olympics. And even when I got beat, it was a kind of a relief. It was like, ‘Oh, thank God I don’t have to do that again.’ It took me a long time to come to terms with what had happened and why I’d done it and, yeah…”

Savannah has never enjoyed spending time away from home, as evidenced when her first professional contract was torn up in Las Vegas after only a few months. For other aspiring athletes, it was a dream opportunity – but for Marshall, it was too far from family and friends.

The pressure of equalling her friend Nicola Adams’ achievements and the unfamiliar surroundings of a bustling Olympic village unsettled the Brit, sending her tumbling out in her opening fight. Her transition from local hope to national expectation had toppled any comfort or confidence.

When asked whether the pressure placed upon female boxers particularly, had contributed, Savannah explained, “I put that much pressure on myself, it got to the point where I didn’t even want to be there. And I’ve come to terms with it now that I threw my whole dream away, because the pressure got too much and I didn’t want to be there. I gave everything away, but that’s when I started growing as a person, if that makes sense?”

“Growing up, I was so shy and timid when I used to box as an amateur. I’d never tell anyone. I’d never tell my mum or dad that I had a bout coming up or anything like that, and they had to find out through my coach. Whereas now, it wouldn’t bother me if there was anyone or everyone in the arena. Now I always think, ‘I can’t wait for more people to see my skills. I can’t wait for more people to know how good I am.'”

“I think if I was more like, ‘Oh my God, there’s thousands of people there. Oh, I can’t do anything wrong,’ then that’s when the pressure comes. I knew everyone was there and I knew everyone was watching me and everyone was expecting. I was ranked number one in the world, I was favourite for the gold coming off becoming World Champion. So that’s when I allowed the pressure to beat me.”

Stepping down from the ring apron for the final time that afternoon in Rio asked more questions of Savannah than it answered. Boxing, a sport famed for its single-mindedness, had taken its toll. Everything was manageable when competing nationally, able to return to the modest family home. But overseas, staring at the walls of her temporary accommodation in Brazil, the silence was deafening. Returning to England with the rest of Team GB was deflating, but necessary as part of her rebuilding process, still smiling through gritted teeth, though frankly disillusioned.

The Rio Games later ended in disgrace, with boxing’s place in future competitions shrouded in uncertainty after judging scandals were exposed. Michael Conlan, the Irish favourite, famously threw his middle fingers towards the panel after losing to Russian squad member, Vladimir Nikitin. Judges were banned in the aftermath and the AIBA was in disrepute. It only rubbed salt in the wounds of the twenty-eight year old, Marshall. Entering a tournament of such high stakes with the possibility that results were pre-determined only pushed her further from boxing. But out of the blue, when one door had slammed shut, another gently opened.

“At the time it was a big kick in the teeth and I thought, ‘Do you know what? I’ve given my life to this sport, I’ve had enough.’ I was going to retire after 2016. I never had any ambition to turn pro. And that was my second crack at the Olympic Games.”

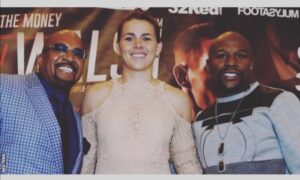

“I was approached by someone through Mayweather [Promotions] who were interested in me and they wanted to offer me a contract. So for me, I’m all about signs and I believe that when things happen, take the opportunity. So once that offer came, I just thought, ‘Why not? I’ve got nothing to lose.’ And what an opportunity.”

Floyd Mayweather. Returning to fight Conor McGregor. Las Vegas for her debut. What more could she ask for?

“I thought, ‘This is it, I’ve made it.’ Obviously, it didn’t pan out anything like that. But it’s just the way it is… I was with Mayweather, then I was with [Mick] Hennessy, now I’m with Matchroom. I feel like I was swimming at the deep end and I’ve personally learned the hard way. I know there was lads from the GB squad who I went to the Olympics with [who have won titles]. There were 14 in all, and I’ve only had eight bouts but we all turned over at the same time. I do feel that I’ve learned quite quickly about the business side of the sport.”

Vegas and the bright lights that always accompanied her initial choice of promoter didn’t suit the homebird from the North East. It was never going to last. Marshall is now looking to utilise that learning for the remainder of her professional career, soon facing the unheralded Brazilian, Geovana Peres, for the WBO light-heavyweight title in Newcastle. That bout is her first opportunity to match that crowning performance in the amateur World Championships, only this time without the head-guard.

Expected to beat Peres comfortably, Savannah feels perfectly primed to begin her reign at the top of the sport. Her recent success and surge in confidence has come after linking up with renowned trainer, Peter Fury. The pair were thrown together almost by chance, after the timid fighter’s failed American experiment had seen her return to the UK. The brain behind Tyson Fury’s dethroning of Wladimir Klitschko and current trainer of his own son, heavyweight contender Hughie Fury, Peter had expressed uncertainty around training his first female fighter. That soon changed though, and the pair have enjoyed an unbeaten start to their working relationship. Fury is one of British boxing’s great thinkers and his approach to training has rubbed off on his new charge.

“Confidence-wise, my whole mindset is totally changed through Peter,” she explained. “I used to hate sparring because I’m that competitive, I used to have to win every spar. If I got caught with a shot, I’d go home and that’d be my night ruined. That’s how competitive I was. But now, Peter’s kind of like, ‘I don’t care if you get beat up. I just want to see you get this one shot.’ And now, I love sparring more than anything. I’d spar every night of the week if I could. Like I said, I enjoy the pros a lot more than what I ever did in the amateurs because there’s no pressure on me. I guess I get beat up in sparring all the time, and I get called for stupid shots, but that’s just part-and-parcel of general learning and progressing. I think that’s all down to training with Peter.”

“Peter is a very, very smart man. And to be honest, if he would have told me two and a half years ago, if he would have said, ‘Savannah, switch to southpaw,’ I would’ve been like, ‘No way. I don’t think so.’ (laughs) If he’d have said, ‘Savannah, put your hands down,’ I’d be like, ‘No, don’t feel safe.’ He’s got me doing things that I’d never, ever thought I’d be able to do.”

There was a comfort to Savannah when discussing her current situation. Despite the ups and downs of boxing as an elite amateur, folding under the pressure of the Olympics and stumbling through the beginning of a shaky professional career, she has finally found peace amongst the constant noise of our sport. With Peter in her corner and Matchroom pushing her on televised cards, in just over a month, she can add the WBO World title to her previous, stellar accomplishments. It’s been a long time coming.

Despite boxing’s obsession with internet feuds, long-running storylines or adversity, Marshall prides herself on a balanced normality. She wasn’t a loud-mouth and refused to buckle when harassed by rivals or opposing fans online. It just wasn’t why she laced up her gloves. Cycling to the Headland amateur gym years ago, battling the elements, it couldn’t have been simpler; competition and a need to apply herself.

The unbeaten fighter has one eye on the World title, but interestingly another eye on the exit, with boxing only ever temporary. Emerging from Hartlepool during some of its tougher times, she was focused on education and employment. It was refreshing to hear about a passion for art and the building industry, as she beamed about potentially enrolling in college or University, with the hope of carving out a career in something stable, and safe. Too often, boxers chase their dreams between the ropes until they can’t keep up the pace. But Savannah Marshall isn’t like many other boxers – that alone makes her story compelling.

“I’ve been a full-time boxer since I was 16, so really, I’d like to go back into education, go to Uni, and that kind of thing. I’ve got other interests. I’m interested in construction, and drawing, and things like that. So there’s lots of other things that I feel like I missed out on for the fact of dedicating my life to the sport. To be honest, I do this for myself. I do this because I’ve got my own goals and I know what I want to achieve. I’ve never boxed for anyone else.

“Once I leave the sport, I don’t think I can be involved in it. And I’m one of them people where I’m very competitive and I’d always want it to be me. I couldn’t just… Even when I watch boxing, I think, ‘Oh, I can’t wait until I’m fighting.’ I’m the type of person that when I do something, I like to give it my all in everything. And I think that that’s why, when I do walk away from the sport, I’d like to put my all into something else.”

Interview written by: Craig Scott

Follow Craig on Twitter at: @craigscott209