The walls are ironically plastered with colour. Blue, white and red, predominantly, with flashes of military green. The stories told on crumbling concrete and painted murals of a time best left forgotten were the backdrop to the darkest times here on the Shankhill Road, Belfast.

Now visited year-round by tourists keen to breathe in Northern Irish tradition, the peace walls that were set up in 1969 remain, whilst similar divisive constructions in Berlin have fallen, decades ago.

It wasn’t as simple as moving on for the local community here in Belfast, with many residents hurting most recently after the tragic loss of journalist, Lyra McKee, originally from Belfast but shot during a riot in Derry this spring. It had been attributed to the ‘New IRA’, taking place following police raids during preparations for the Easter Rising parades. It was a unnecessary reminder of what used to be.

Fighting was often the only sense of unity in these parts, with former world champion, ‘Clones’ Cyclone’ Barry McGuigan bringing Catholics and Protestants together. Boxing was pure. Honest men standing toe-to-toe, pouring everything into combat for twelve or fifteen rounds and embracing on the sound of the final bell. Why wasn’t life that simple? McGuigan had went to work in various venues across Belfast, yet made his debut in Dublin during the height of the Troubles. He was a symbol of hope for the younger generation, inspiring pride amongst the Irish from either religion.

As one Irish fighter hung up his gloves, it was time for another to embark on a thrilling career. Born at home, on the notorious Shankhill Road itself, Wayne McCullough(27-7, 18KOs) had seen it all. He’d hit the gym before returning to see men shot on the street and witnessed bombings first-hand in an area he’d always called home. The ‘Pocket Rocket’ was destined for bigger things, explaining that he decided from an early age, ‘there must be something better than this’. Wayne decided to wear neutral-coloured trunks and select entrance music with no allegiance to the violence that littered the city – it was boxing and nothing else.

As McCullough, now forty-nine, embarked on his professional career in the United States, the street he’d been born and raised on was bombed in October 1993, leaving ten dead. Whilst others would have become restless or distracted, he became laser-focused on achieving championships for his family and his country – both sides of the wall.

Life after boxing for the Santa Monica resident was also tumultuous, losing friends and money along the way. But where better to start than the Shankhill, where boxing adorns one of the many murals, forever remembered on Hopewell Crescent.

“I was born right in the middle of it [the Troubles]” Wayne explained, detailing his childhood. “I was actually born on Percy Street at home, because we didn’t go to hospital. We moved to the outside of the Shankhill and it was to the Highfield Estate. I lived there until I left to come here [the USA]. We saw paramilitaries, of course, I grew up amongst it all. I seen stuff happening. I seen bombs going off, people being killed. Why can’t people just get along with each other?”

“Boxing always crossed the divide – even back then. I grew up in the midst of it all, when I was doing my roadwork through the Protestant area and I’d maybe cut through a Catholic area – nothing ever happened. It was always safe, nobody ever bothered me. If people can get on for five minutes with each other, why can’t they get on with each other all the time?”

“Things have changed a lot in the last twenty years, but growing up then, you had to know where you were going. If you were a Protestant going into a Catholic area or a Catholic going into a Protestant area, you had to know if you were in the wrong area. Otherwise, you wouldn’t have lasted five or ten minutes. People would have got to know you in two minutes and maybe beat you up or something really bad could have happened. It was just the way it was. It was drummed into the young kids at an early age that you just hate each other.”

That hate, demonstrated even now at sectarian marches or football matches seemed unfounded to the newer generation. The young McCullough had no reason to hate, coming from a family that channelled loyalty and affection. Those peace walls that seemed to contain the community, prisoners in their own homes, represented segregation of the social classes, as much as a bloody religious split. Families bred on the Shankhill or the Falls Road had little to celebrate. For a long time, that was their reality.

“They put the wall up and they put it up in a working class neighbourhood in the Shankhill Road. The Falls Road and the Shankhill Road actually had streets running parallel to each other, but they put a wall down the middle and separated the working class people. It’s funny how the rich people lived together, since ’59. If it was really about religion, it doesn’t matter if you’re rich or poor, you can’t live next door to each other. They blamed the working class people for hating each other, when really they were the ones who would socialise together.”

Socialising soon became a thing of the past for McCullough, who had thrown himself into every sport imaginable. That was standard procedure for a young, Belfast boy. With two older siblings, he would follow them blindly whether it was football or track-and-field. It’s tricky to know, looking back, if fighters are ever acutely aware of what they could go on to achieve when blinded by their own optimism. Wayne seemed destined to make an impact from a young age, focusing solely on the Sweet Science when still at high school.

“I just went along to the gym with my brothers. I went to the gym with them and then all my friends came to the gym, I was only about seven years old, but it kept me off the streets. I was doing cross country running and football at school, rugby at school [as well] until I was nine, ten, eleven and twelve but I just kept going to the boxing gym. I knew I was better at boxing than I was at the racing and stuff. I knew when I was about fifteen that I could make a career from it, so I dedicated my life to boxing.”

McCullough forced his way into the podium positions at various championships both nationally and overseas, moving one step closer to pursuing a career in boxing. There were some historic bouts in his midst, with major amateur tournaments just around the corner. Wayne knew that his performance in both the Auckland Commonwealth Games (1990) and Barcelona Olympic Games (1992) would open him up to a host of top-class trainers and promoters and although still young, he made sure he didn’t disappoint, with the weight of a torn nation on his shoulders.

He explained, “When I was fifteen, I knew then that my goal was to be the WBC champion of the world. I wanted the WBC belt so bad, but I knew I had to do something in the amateurs from age fifteen to turning pro to get some decent sort of contract. To be a professional, training two or three times per day, you have to dedicate your life to boxing. I got the Commonwealth gold medal in Auckland, New Zealand. I was gonna turn pro then, but I went to the Olympics in between and carried the Irish flag in the opening ceremony.”

“I won a World Cup bronze when I stepped up to bantamweight and two years later, I was a bantamweight for the Olympics in Barcelona ’92, bringing back my silver medal. Going to that Olympics, my goal was to get at least a bronze. It was a stepping stone to the paid ranks – I knew I wanted to be a world champion, professionally. I knew I had to get that contract that would secure me full-time. It happened for me, thank goodness. I got the offer to come to Las Vegas and train under Eddie Futch, who I believe was the best coach that ever lived. The rest is history – I became world champion.”

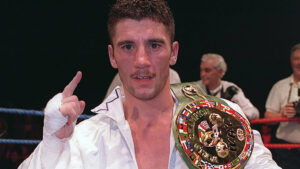

Throughout his professional career, McCullough wasn’t shy when faced with a challenge, fighting the best whenever possible. He would go to war with names such as; Scott Harrison, Daniel Zaragoza, Oscar Larrios, the great Erik Morales and an ‘underwhelming’ ‘Prince’ Naseem Hamed. In bouts that stretched from Atlantic City to the beautiful fight capital of Las Vegas, Wayne captured and twice defended the very same WBC bantamweight title he’d once dreamt of. Regardless of his defeats to the champions mentioned above, Wayne fondly remembered his best night between the ropes in the Aichi Prefectural Gymnasium, Nagoya, Japan.

It was his seventeenth fight, by far the furthest from anything considered ‘home’ and he was facing the defending, champion and local favourite, Yasuei Yakushiji. Capturing the title on foreign soil was his proudest moment, fulfilling that ambition held since aged fifteen. McCullough and the legendary Eddie Futch had upset the odds, but it was nothing less than they had expected. On that warm, summer evening in Japan he became a world champion and also the answer to a pub quiz sports’ question, which he only later became aware of.

“Going to Japan, no British or Irish fighter at the time had went to Japan and won a world championship”, explained a nostalgic Wayne. “I had to go into the guy’s backyard, it was actually his hometown of Nagoya, Japan. He was making his fifth defence of the championship and nobody gave me a chance. The media from Ireland and Britain didn’t even turn up. The American media had me as a slight favourite, but that’s cos they seen me fighting in America. We expected the Korean judge to score against us, but I won the fight and took the WBC belt.”

“I became the first fighter to do it, up until last year with TJ Doheny, he went to Japan and won the belt. Nobody ever told me I was the first! I just wanted to win that belt. Beating that guy in his backyard was probably the highlight of my whole career.”

With Futch by his side, nothing felt impossible. The bond shared between an eighty-two year old trainer and his twentieth world champion was unusually tight. Wayne had demonstrated his willingness to learn from the man he dubbed, ’my internet’. He had been Futch’s last project, taken on whilst he was training multiple world champions, approaching the end of his storied career. As McCullough now trains fighters and actors in Santa Monica, he channels those teachings from Futch.

“My manager at the time, Matt, he was a TV executive. He’s the one I signed with and he came over to Ireland to meet me. I thought for him to come all the way over, that was a great thing. They talked about Janks Morton, who was one of Sugar Ray Leonard’s trainers, who was gonna be in Baltimore. But two weeks before I left, Eddie Futch – who was gonna retire because he was getting old – he had a look at me and Eddie said, ‘The kid has it’. He signed me up. He was in his eighties, people thought after [Riddick] Bowe he was gonna retire. He decided to take me on. I thank God that he did.”

“At that time, he was training Bowe, who was the heavyweight champion of the world and Mike McCallum, who was a three-time world champion. So, I was in training camp with these guys and I remember thinking, ‘I can’t believe this guy is even having a second thought and training me’. I couldn’t believe it. The stuff he taught me, the small things, he didn’t really change anything but he tidied me up and made me a professional. I was probably closer to Eddie than any other fighter was.”

“Before he passed away, he gave me a letter and signed it, ‘You will be a trainer one day’. I just listened to him so well. You’re sitting there over dinner and for two hours, he’s talking about when he was sparring with Joe Louis in the thirties and forties. I’m like, ‘Is this real?’ It was like the internet – but we didn’t have any internet then! He was my internet and he would teach me everything about boxing. One of my favourite fighters of all time was Henry Armstrong and he would talk about guys like that. I was just like, ‘Wow’. It was like going to college. He had twenty world champions and dozens of contenders, but I was the only one he gave a signed letter to. It’s priceless.”

Eddie Futch passed away in 2001, aged ninety, but his education lives on. Fighting had come to an end for Wayne after suffering defeat against Juan Ruiz in the Cayman Islands in 2008, returning three years after his penultimate contest. Recurring back injuries and subsequent hand injuries had plagued him as he moved into his mid-thirties, signalling the end of a successful career with his ambitions realised. Now based in the United States, he decided to move into training and started building his own stable, with a love for the sport tested over time.

“Fighters – they’re not loyal people. I trained one Mexican fighter, who fought Mikkel Kessler for the world title in Denmark – he lost. He decided instead of paying me 10%, he would pay me 2%. I got a bad taste in my mouth for about five years after that. I didn’t do anything from 2007 until about 2012. My wife kept saying to me, ‘You love this sport, it’s not about the money’. I told her, ‘They take the love away from you’. She said, ‘Why let them win?’ It’s always good to get a speech from your wife! You’re not doing it for the money, you’re doing it for the love of the sport. So I decided to get back into it again.

“I used to train with Freddie Roach for my last few fights. He was trained by my trainer, Eddie Futch, and I asked him where to sign a contract with him, but he said, ‘You don’t need one, I trust you’. Freddie trusted me and I had three fights with him. Didn’t have one problem with it. With Eddie, I gave him 15%. The going rate was 10% but I would have given him 20%, it wouldn’t have bothered me. It was well worth it. Some of these guys are paying their manager 25-33%, but the manager is never there. He’s there once a week. The trainer is there every day, but that happens a lot. I just thought that fighters were like myself and were gonna pay (laughs)!”

Sadly, that pathetic 2% split of a purse wasn’t the only time that Wayne had his fingers burnt. His manager, Matt, had also betrayed his trust. The man who flew to Ireland with promises of fame and fortune for a young McCullough had approached him sometime after the pair had parted ways to get something off his chest. He’d waited just long enough.

“In ’97-’98, Stuart Campbell was my lawyer, but he was also my co-manager with my wife. Little did I know, along the way that Matt was screwing me over. He owed me $1million. He told me face-to-face that I was past the Statute of Limitations – of course I wanted to rip his head off. We looked into it. He lives up in Santa Barbara, which is a rich neighbourhood in California where he lived off my money. He made millions with me, but when his Uncle passed away he got another $30mill or something. It happened to Mike Tyson, he was screwed over. People think he made $300mill and spent it – he didn’t. Other people spent it for him.”

The forty-nine year old had been rewarded by boxing, yet doubly betrayed. His relationship with Matt was ruined, with their work together in the past now tarnished, though working with his wife, Cheryl, had restored some semblance of faith in the sport. McCullough was still accompanied by his jagged, dark beard and still retained a modicum of enthusiasm for boxing, despite its tendency to let him down.

His last bout, facing the unheralded Juan Ruiz, was the beginning of the end. Despite the tired, constant rhetoric of a return to form, Wayne had suffered in preparation, struggling through one last gruelling camp. The former champion surrendered himself after the bout, struggling on the medical table. It was a cruel way to go, but he’s since made peace with it.

We spoke about the sport of boxing and its future. What would be needed to secure fighters and their families? For the Northern Irishman, it was pretty obvious. Protection. Not in the way of head guards or shorter rounds, but the additional support provided long after boxer’s hands start to tremble or their memories lead them a merry dance. It was a nice idea, yet seemed as far away from reality now as ever before.

“I think first-and-foremost, we need to have a boxer’s union”, explained McCullough. “Why can’t a fighter start to have a pension and stuff like that? Even a guy fighting for a thousand dollars, if you took fifty out to put towards their pension, it all adds up. Maybe their pension would be smaller than somebody making a million dollars, but if there’s always something at the end of the tunnel then you’ll help the fighters who end up broke. A lot of promoters end up getting greedy instead of helping the fighters.”

“It’s the same with referees and judges. I believe to this day, if you turn the sound down when I fought Hamed, I won the fight. He ran from me. Hamed had just signed with HBO and every punch he missed they were calling it a shot, it was a joke. When you have things like that, they’re protecting their asset. I could have stood there in the corner and had a cup of tea, doing nothing all night, he wouldn’t have come near me. When a bad decision is given, the Zaragoza fight, my first fight with [Oscar] Larrios, everybody thought I won the fight. Commentators and everything. The announcement was read and I lost the fight by a wide margin. Nothing gets done about it. We’ll see how long it takes…”

Despite memories of his own time as a world champion, McCullough was left wanting more from boxing. The husband and father had come to realise it wasn’t that simple. His passion, nurtured through years spent within touching distance of boxing’s elite, was left largely unrewarded. Wayne had thrown himself head-first into a sport that never guarantees satisfaction, let alone fairness. He was out of pocket to the value of seven figures. But still, he managed remain positive.

The defeats he’d suffered when facing Daniel Zaragoza or Oscar Larrios were cast aside, marking an otherwise stacked record of professional victories. Boxing was boxing – it was deceit and it was a lack of loyalty. It was doubtful that narrative would change. He’d experienced theft first-hand, from his own manager, though discovered too late. That was the game, whether he liked it or not. Thousands of miles from the devastation that once rocked his family and friends, he was safe in the sunset of Santa Monica, far from the blood spilled between neighbours in darker times.

“In amateur boxing, there’s a lot of politics” Wayne explained, “But in professional boxing, most boxers want to fight. I’d say, from day one, get yourself a good lawyer, get yourself a good accountant and make sure that when the money is coming into your account. Every penny goes into the account and not into someone else’s pocket. We love boxing so much that we forget about what other people are doing behind our backs. Make the money for yourself. When it’s all said and done, you’re still a young person, if you haven’t got enough money to last you the rest of your life, you have to get a job, what do you do? Just make money for yourself and keep an eye on what’s going on behind your back, that’s all I’d say.”

Interview written by: Craig Scott

Follow Craig on Twitter at: @craigscott209