There were more bodies than beds, cramped into the one-bedroom apartment in Trujillo Alto, Puerto Rico. Bent like a little contortionist, the youngest of the struggling Mendez family wrestled with the searing heat during his attempts to sleep, following another day of hard graft. In Caribbean Islands such as Puerto Rico, education lands a distant second for many of the children wandering the streets, selling whatever they can get their hands on. With mother and father briefly separated in Caguas, the Mendez siblings were later reunited with both parents, moving the family to the Northern Coastal Plain.

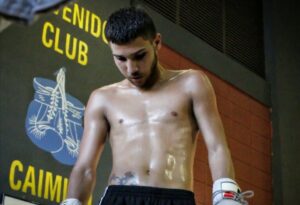

It was back in Trujillo Alto that Wilfredo Mendez (15-1, 5KOs) would earn his crust, toiling with tourists whilst his peers in the capital were picking up their books in air-conditioned classrooms. He was only five years-old. Fighting wasn’t always in his blood, but survival had become second nature after escaping continued poverty and homelessness in the United States. Now crowned WBO minimumweight, world champion, it was time for ‘Bimbito’ (‘The Child’) to tell his story.

Only twenty-three years old, Mendez had bounced back from an unexpected defeat, joining Wanheng Menayothin – of Floyd Mayweather record-breaking fame – as one of the sport’s lightest division’s titlists. Unlike the Thai champion, he’s flown largely under the radar, often overlooked as his countrymen have taken centre-stage. But now, Wilfredo is the only reigning Puerto Rican world champion and has prioritised prospective unification bouts.

This year could provide Wilfredo with his chance to seize the limelight, often difficult for fighters weighing just 105lbs – left behind by television networks of powerful promotional companies. He has travelled too far to quit and has toppled adversity on multiple occasions. Mendez is a champion now, recognised for his talent and dogged conviction, but it hasn’t always been that way.

On humble beginnings, the reigning champion explained, “I was only five years-old. I lived with my mother and my brother in an apartment in Caguas without water and without any electricity. Then, when my parents got back together I was seven years-old and we moved to a different city. We started living in a very humble one-bedroom house. My mother, father, older brother and I slept in the one, tiny room. At that time, I worked to be able to have money for school and to help with things for the house. I was making handmade necklaces and selling things made from mud, just for money.”

“I signed up for boxing to follow in my brother’s footsteps and to look for a better future. I just wanted to get ahead. I was looking to qualify for the Puerto Rican national team. I finished my fourth year [of school] and then studied for my qualification to become a barber. I was seven years-old when I first visited the boxing gym – I really didn’t like it.

“When I started, I felt the atmosphere in the gym was very tense. There were many intimidating people who thought they were the best. That’s why I started badly as an amateur, losing my first SIX fights. People went on, telling me that I was undefeated in taking [consecutive] losses, but as time went by I developed skills. I watched fights and I learned a lot of technique and gained intelligence. I fell in love with boxing and I competed about 180 times as an amateur.”

Although he would eventually force his way into boxing’s good graces, Wilfredo’s experience in the United States as a child had shaped him – without fear and hardened after experiencing crippling disappointment. His mother was his confidanté, but her gamble hadn’t paid off. Huddled under the tunnels of Southern New England, Mendez would have to wait for his chance to crack the American market.

The sport of boxing has always been a game of risk; stick or twist. Life couldn’t always be compared, but in this case, mother and son decided to roll the dice. After being separated from his father during his two-year hiatus, and without a safer alternative, optimistic parent and child travelled to the mainland. The American Dream appeared to fly over both Wilfredo and his mother’s head – when a roof was all they needed.

“The most difficult experience that I had to live through was in Connecticut, USA. At six years-old, my mother decided we should go there to look for a better future. I had some cousins who were going to help us. We left [Puerto Rico] with nothing – just luck and honesty. When we got there, they never helped us.

“We stayed on the street for a month with absolutely nothing. I had to spend nights in the street, going hungry. There was no money and we couldn’t speak English. I know that my mother spent a long time walking with us to places that gave free packages of food and milk. That helps me never lose humility and I will always help people with whatever I have in my hands. It helps me to have my feet on the ground and not to believe in myself more than anyone else.”

Mendez’ career to this day has been relatively short-lived, debuting only three years ago. That scared child attempting to sleep in the parks of Connecticut has grown into a respected and under-appreciated, world champion. His progression from habitual, losing amateur to recently crowned, national treasure has passed fans of the sport by, but it was undoubtedly hard-earned. He had dreamed of following in the footsteps of fighters like Fajardo’s great Felix Trinidad, recapturing a portion of boxing’s top prize for Puerto Rico.

“For my world title fight, I had to make these sacrifices. Number one; I had to leave my job and devote myself to full-time boxing. Morning, afternoon and night. Number two; become a ghost, practically. I left all of social media networks. I didn’t want to let people frustrate me with their bad vibes and damage my dreams. Number three; Get away from my family for ten weeks of training. I was based in a field, where I was away from the city. I didn’t have a cell phone signal, I didn’t have any internet.

“I had to endure so many negative things from people, I only needed my family. I had a lot of pressure since all of the previous champions from my country had lost their belts. Their only hope was this young boy. I think back to my debut in my home town, I had to sell one hundred tickets so that I could pay my opponent, pay myself plus cover my space on the event. In my third fight, [manager] Raúl Pastrana saw me compete and we became like brothers.”

As he moved towards his own silver lining, the young Puerto Rican was forced to embrace the struggle of returning from defeat before he would climb to the summit of the minimumweight division. He’d suffered his only loss just eighteen months ago, when beaten by a handy, Leyman Benavides who was expected to be no more than a measuring stick. His opponent was there to lose, with six defeats already on his ledger before the pair touched gloves. Things don’t always go to plan. Mendez was humiliated and candidly admitted struggling with public expectation.

Wins against mediocre opponents shortly after signalled an intention to continue learning, working towards titles and redemption for himself. Puerto Rico had been starving for success, looking for their next star following the retirement of national icon, Miguel Cotto. It has been a hotbed of talent for decades, birthing former champions such as Wilfredo Benitez, Hector Camacho and trailblazer Sixto Escobar. Mendez found himself paddling in boxing’s shallow end however, fighting the smallest men, generating nominal purses, but it was about legacy from this point on.

“I have always felt blessed by God and, above all, very proud,” Mendez told me. “I was able to end my country’s drought of world champions and I’m currently the only champion from Puerto Rico. My reaction was just to cry, as winning was something that felt very sentimental. I remembered how difficult the camp was and how much I had to sacrifice in order to achieve it.”

“Since I made my debut, I have always been fighting with my mind, reinforcing it day-by-day and preparing it for everything. With my feet on the ground, of course I am still world champion and I have already made my first defense. I have to remain the same, since some boxing fans start to dream. They are the same people who could take you down overnight. Fighters are always fighting with their mind – there is nothing worse than that.”

The constant struggle endured by fighters mentally wasn’t new to Wilfredo Mendez. He’d lived it, long before lacing up his gloves. Isolation or tackling setbacks wasn’t new to him, infact, at only twenty-three and barely an experienced professional himself, it seemed life may have taught him more than boxing could. However, the sport has plenty of time to catch-up. With his popularity on the rise, and fresh from his visit to the WBO convention in Japan, he remains keen to stamp his authority on the new year.

Despite emerging from humble beginnings, ‘Bimbito’ was blessed with an awareness of the business side of boxing. He knew that little men wouldn’t draw those pay-per-view audiences, but what could he do? He didn’t have two cents to rub together when sculpting models out of dirt as a toddler or turning away from the harsh winds of Connecticut winter. Performing, winning and carving his name into the history books were all within his gift. The other stuff was pre-determined. He would never be a heavyweight. Without electricity or safe shelter, he’d survived on instinct as a young boy – that was fighting.

“My weight class just seems to be one that people like least and there is less pay as a result. But we are fighting the most and we have all of the ability. Unlike other divisions where their fight ends at any time with a single blow, you might not get to see an entertaining fight. That’s why I think all boxing promoters should give more exposure to smaller weights. I want to make more history and place myself among the best in my division – just like my fellow champions.

“In each fight, I feel that I am evolving, gaining more confidence in myself and especially improving my technique. I have a style like Ivan Calderon. I would like to achieve all of my goals. That would be; to beat the best, to unify the division, have five defences of my titles and make bags of money to retire at a young age, so that I can enjoy life with my family. We have the opportunity to make history, even during our short careers.”

Interview written by: Craig Scott

Follow Craig on Twitter at: @craigscott209