In this time of a worldwide boxing shutdown, thoughts tend to drift back to times past, fights seen, champions remembered. Lately I have found myself thinking of Carlos Monzon.

It’s possible that Monzon was the greatest middleweight champion of them all. Tall and rangy, he was an excellent technician with a sturdy chin. He could punch, too, using his long left jab to set up a siege-gun right hand.

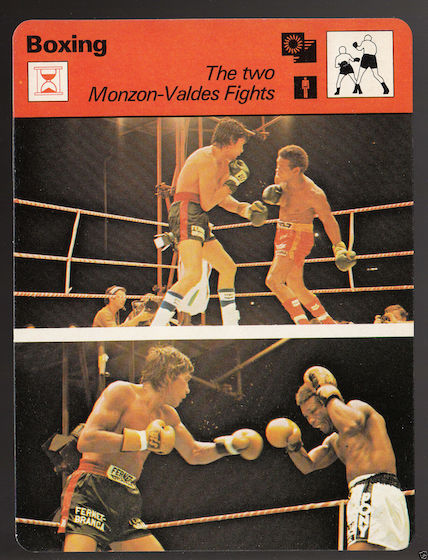

I was able to see Monzon on site in four of his bouts in Europe, including the two with his biggest rival, Rodrigo Valdes, which took place in Monte Carlo in 1976 and 1977. Monzon won each bout on a unanimous 15-round decision but both fights went down to the wire on the scorecards.

Monzon cut a commanding figure in the ring and out. He had the look of a winner even if opponents were competitive.

There was, it seemed to me, an aloofness, almost an arrogance, about Monzon. At the time of the Valdes fights he had been starring in movies in Argentina. He carried himself like a film star.

An abiding memory is of Monzon striding into the Rome office of his promoter, Rodolfo Sabbatini, who was his European agent. Monzon was dressed in a white suit, which accentuated his bronzed features, and he was smoking a cigarette. He looked as if he had just stepped off a Federico Fellini movie set.

The Colombian Valdes was an altogether more approachable man, although a champion in his own right. I’ve got a photo somewhere of me shaking hands with Valdes in Monte Carlo.

At the time of the first Monzon vs Valdes bout, at the outdoor Louis II Stadium, there were just two world sanctioning bodies. Monzon was the WBA champion. The WBC had vacated the title when Monzon failed to defend it against the No 1 challenger Valdes (I believe the two sides couldn’t agree on terms). Valdes had won the vacant WBC title by stopping Monzon’s old rival Bennie Briscoe in the seventh round of a violent fight in Monte Carlo (I was ringside for that one, too).

The stage was set for an epic battle-of-champions showdown. Monzon had not lost a fight since losing a points decision back home in Argentina 12 years earlier. He had avenged the three defeats on his record. The bout with Valdes was Monzon’s 13th championship defence.

Valdes, too, was on a long unbeaten run. His last defeat had been on a split decision in New York six years earlier and he had made four successful defences of the WBC title. Monzon was 33 years old, Valdes 29.

Monzon’s blonde actress girlfriend Susanna Gimenez, in (as I recall) a low-cut blouse and shimmering, skin-tight gold lamé trousers, was a striking presence. I believe Rodolfo Sabbatini urged that Susana be quartered in a separate hotel from Monzon before the bout to avoid “distraction”.

Valdes had been challenging Monzon for years – ‘calling him out’ as we now say – so the tension was palpable as the fighters waited for the opening bell on that warm summer evening.

The physical advantages were with Monzon, who stood almost 6ft. Valdes, who turned professional as a lightweight, looked significantly the smaller man in the ring. Clearly, the fight plan for Valdes would be to take the fight to Monzon and try to crowd him and hurt him, not let him get settled.

However, Valdes just couldn’t seem to get into the fight in the early rounds. His New York manager, the veteran fight guy Gil Clancy, was urging him to keep the pressure on Monzon. However, Monzon was controlling the fight from the centre of the ring and by the fourth Valdes was noticeably swollen under the left eye.

Yet Valdes lived up to his ‘Rocky’ nickname as he kept pressing forward, and in the eighth round he rocked Monzon with a big right hand.

The fight had now developed into a gruelling struggle but Monzon, ice-cool in the heat of battle, stuck to good, solid, basic boxing, the one-two in particular, and began to add body punches and uppercuts. Valdes, though, was coming on strongly and he was doing a better job of getting under Monzon’s punches and launching his heavy-hitting attacks.

It was a tough fight for both men. Valdes had some swelling over the right eye as well as the lump under his left eye while Monzon had bruising under the right eye.

Valdes was throwing some bombs but Monzon leaned back over the top rope and it wasn’t easy to catch him with flush shots (Gil Clancy told me afterwards that he had complained before the bout – to no avail – that the ropes were too loose).

A knockdown in the 14th round was a decisive moment in the bout. Valdes seemed to be closing the gap on points when he just seemed to walk into a right hand and he fell forward so that his upper body was over the middle rope as he faced out into the crowd.

Although Valdes scrambled to his feet quickly and was coming forward again by the end of the round his momentum had been slowed. The French referee, Raymond Balderou, who scored the fight along with two judges, told me afterwards that if it hadn’t been for the knockdown he would have had the fight a draw.

It was Valdes who closed the stronger in the 15th round, landing the left hook and the right hand, but Monzon scored with a well-timed right uppercut. Both men threw their arms aloft at the final bell but the referee and the two judges agreed that Monzon was the winner wth scores of 146-144, 147-145 and 148-144. The knockdown in the 14th was huge for Monzon – a possible 10-9 round in Valdes’ favour turning into a 10-8 round for Monzon.

There was no real disagreement about the verdict among ringside observers I talked with after the fight. Most saw it as a close contest. British middleweight champion – and future world titleholder – Alan Minter, seated in the row behind me, had Monzon a clear winner. WBC president Jose Sulaiman had Monzon winning by just one point but, of course, Valdes was his organisation’s champion.

An American news agency reporter said he had Monzon winning widely and didn’t see the fight as particularly close. This angered a British fight fan at ringside who told me: “People who didn’t see the fight and go by this guy’s report will get a completely wrong idea of what fight it was.”

Contender Vito Antuofermo (New York based but still an Italian citizen) was ringside and, although a 154-pounder at the time, fancied his chances against Monzon. “As far as I’m concerned there are still two world middleweight champions,” Vito told me. “You can’t take anything from Valdes.”

Vito’s immediate goal, though, was a crack at Eckhard Dagge for the WBC’s 154-pound title. He had beaten Dagge by split decision in a European title bout in Berlin and Dagge had just stopped the Bahamian Elisha Obed to become world champ. Antuofermo fancied he could beat Dagge again and face Monzon in a clash of champions. That didn’t happen, but Antuofermo did move up in weight to win the WBC middleweight title and lose twice to fellow-ringsider Alan Minter in championship bouts.

Backstage in Monte Carlo, with Susanna Gimenez gently applying an ice pack to the marking under his right eye, Monzon said that Valdes hadn’t given him his hardest fight but admitted he was hurt in the eighth round. The Valdes faction thought their man had won. Gil Clancy complained that Monzon had been allowed to hit Valdes behind the head all night.

It was the sort of fight that demanded a rematch – and 13 months later the two went at it again in what was to be Monzon’s last fight.