It’s scarcely believable that it is almost 20 years since a thunderbolt of a right hand from Hasim ‘The Rock’ Rahman separated reigning world heavyweight champion Lennox Lewis from his senses in Carnival City, South Africa.

Like James Braddock, Buster Douglas and Leon Spinks before him, Rahman is remembered – or sometimes dismissed – as a man who grew great for a night – to which one might reply, yes, but what a night!

A product of the mean streets of Baltimore – forever immortalised and defined for millennial binge watchers by David Simon’s magisterial TV series The Wire – Rahman’s journey to the most prestigious prize in sports was a circuitous and remarkable one.

As a teenager, he was shot five times and also badly injured in a car crash, leaving him with permanent scars. As he once admitted: “If I didn’t change, I would [now] be in somebody’s penitentiary or somebody’s graveyard.”

It takes impressive fortitude to renounce a life of crime and associations with “bad people in bad spaces”, but to his credit Rahman did it, finding salvation in boxing, although he didn’t lace up a glove until he was into adulthood.

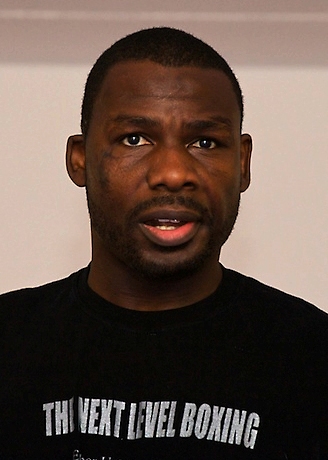

“In Baltimore, I was on the streets from about 14 until the age of 17, 18, 19,” the now 47-year-old tells Boxing Social down the phone from Las Vegas, his voice warm, friendly and frequently animated.

“I walked into the gym when I was 20 years old. I’d been through the worst of the worst in the streets, but if it wasn’t for the streets I don’t think I would have got into boxing.

“I was actually on the streets when I was introduced to a form of boxing. I won a body-punching contest and was told if I went to the gym I’d make a million dollars…”

“Needless to say I went to the gym.”

The dramatic pause Rahman employs is almost as well-timed as the famous right hand that pole-axed Lewis.

It’s a punch that Rahman still – unsurprisingly – revels in describing.

“Actually, a little bit before the finish I hit him with a good right hand, and he smiled at me,” he chuckles. “So I knew I had him! I thought: ‘we’re in a boxing match why did you smile at me?’

“I thought: ‘really? That feel good to you?’ I felt like I had hurt him with that shot, so I said: ‘let me see how much damage I can really do. If he’s smiling let me continue to give him that!’

“So I tried to set him up and hit him with another right hand and the next right hand I hit him with turned out to be the crucial blow that ended the fight.”

Rahman pinpoints his meticulous preparation for the Lewis fight as key.

“I was not going to be denied,” he insists. “He would have had to well, kill me to win. My preparation was second to none and I just had a feeling I would win.

“I dotted all my i’s and crossed all my t’s. Fights are won and lost in the preparation and my preparation was spectacular. I don’t think no heavyweight could have beat me that night.”

When asked to describe how it feels to become the heavyweight champion of the world – emphasis on the – Rahman initially hesitates, unable to find the right words, before they finally tumble out in a torrent of emotion.

“I mean … I’m really not smart enough to come up with the words to describe what I was feeling… but it was… like ecstasy times a billion!

“It was like… wow. I mean Lennox Lewis, I’ve got so much respect for him as a fighter. He went to the Olympics, he won a gold medal, he beat every great fighter in that era, so for me to beat this guy was a major accomplishment.

“There’s a lot of guys out there who have won a regular title, or someone was stripped of a title and then they won a title. There’s a lot of people who become belt holders, but there ain’t a lot of true heavyweight champs and I was a true heavyweight champion.

“For me, it was the epitome of boxing. You can’t get no higher than that. Nothing compares to being the heavyweight champion.

“People speak about Muhammad Ali, Joe Frazier, Joe Louis, and guess who’s along that line with them?”

Talking of Ali, Rahman draws a parallel between arguably The Greatest’s greatest night, and his own career peak – which remain the only occasions when the lineal heavyweight title has been contested in Africa.

“The Rumble in the Jungle,” he intones. “That’s exactly what [his fight against Lewis] reminded me of. The South African people got behind me. I endeared myself to them. I was training in their gyms I was living and eating in their town. I was amongst the people.

“It was an eerie feeling I was like: ‘I’m Muhammad Ali and Lennox is big George Foreman!’ Both of us weren’t given a prayer to beat this big massive obstacle we had in front of us and both of us knocked them out.”

Of course, whereas Ali vs Foreman 2 never happened, Lewis enacted brutal revenge on Rahman a few months after the duo left South Africa, a Las Vegas court having upheld a rematch clause in his contract.

Rahman refuses to blame the courtroom shenanigans for his fourth-round KO loss in Mandalay Bay, Las Vegas.

“I don’t think it affected my mentality for the rematch,” he says. “I felt like I had Lennox’s number and that if I hit him again, he was going to sleep. What happened in South Africa was a big factor in me thinking that but also during our press tour we had an interview on ESPN and we got into a scuffle.

“I felt his strength and I felt like I dominated him in terms of strength, his bodyguard was holding me back and in my opinion I still manhandled him. So I just like felt: ‘oh man, this is going to be easy. He’s not strong enough for me!’

“That gave me a false sense of security. I felt like I didn’t really need a game plan, I didn’t need anything. All I gotta do was get in and hit him. Once I hit him the fight is over. That was my bad.

“I forgot how great of a champion Lennox was. You can’t never just go in and think you can rely on one punch to beat somebody like Lennox Lewis.”

The bitterness of the past that used to envelop Rahman and Lewis has, according to the Baltimore man, now evaporated.

“We’ve been around each other several times since then. At this point, we’re cordial. There’s no animosity. It’s over – it was almost 20 years ago.”

Although the Lewis loss doesn’t seem to irk Rahman, his controversial 1998 showdown with David Tua – in which he was TKO’d in round 10 after being badly hurt by an after-the-bell blow at the conclusion of round nine – remains an itch that it seems will he never scratch to his satisfaction.

“I always felt like I deserved to fight Lennox Lewis earlier and as an undefeated fighter, because I had a title eliminator against David Tua and I was blatantly robbed in that fight.

“When I got my shot, David Tua had already lost to Lennox Lewis and I felt it was justice that I was finally getting my turn. David lost to [Lewis] and he had a victory over me on the record, but he didn’t beat me.”

Despite his keen sense of injustice regarding the Tua fight, what proves most endearing about Rahman is his painfully honest assessment as to why his career only scaled the loftiest of heights for that one, unforgettable night.

“One hundred per cent [if I could change anything], I would definitely train more,” he sighs. “For my first 30 fights nobody trained harder than me, nobody was more committed than me.

“After that I just started going to camp only when I got a fight. That’s when it all went downhill, for real. Because as a boxer you should be training all the time, as opposed to just when you get a fight signed, sealed and delivered.

“I think that’s the fallacy of most fighters – they want to relax, relax, relax, then when they get a fight signed they go to camp. The problem with going to camp is you may or may not get to the point where you were before you got out of shape.

“If I’d just stayed in the gym and done something, worked on my craft more … So, that’s my message – stay in the gym! Don’t just let it all go. Always improve. If you do that you’re giving yourself the best chance for success.”