Upsets have happened all through ring history. Sometimes the favourites really shouldn’t have been favourites at all. Other times, the odds were ridiculously close. During the Coronavirus downtime, I’ve been looking at some of these fights. All were fights where a sharp player could have made the proverbial killing. Here are three famous fights where the betting odds were hopelessly askew.

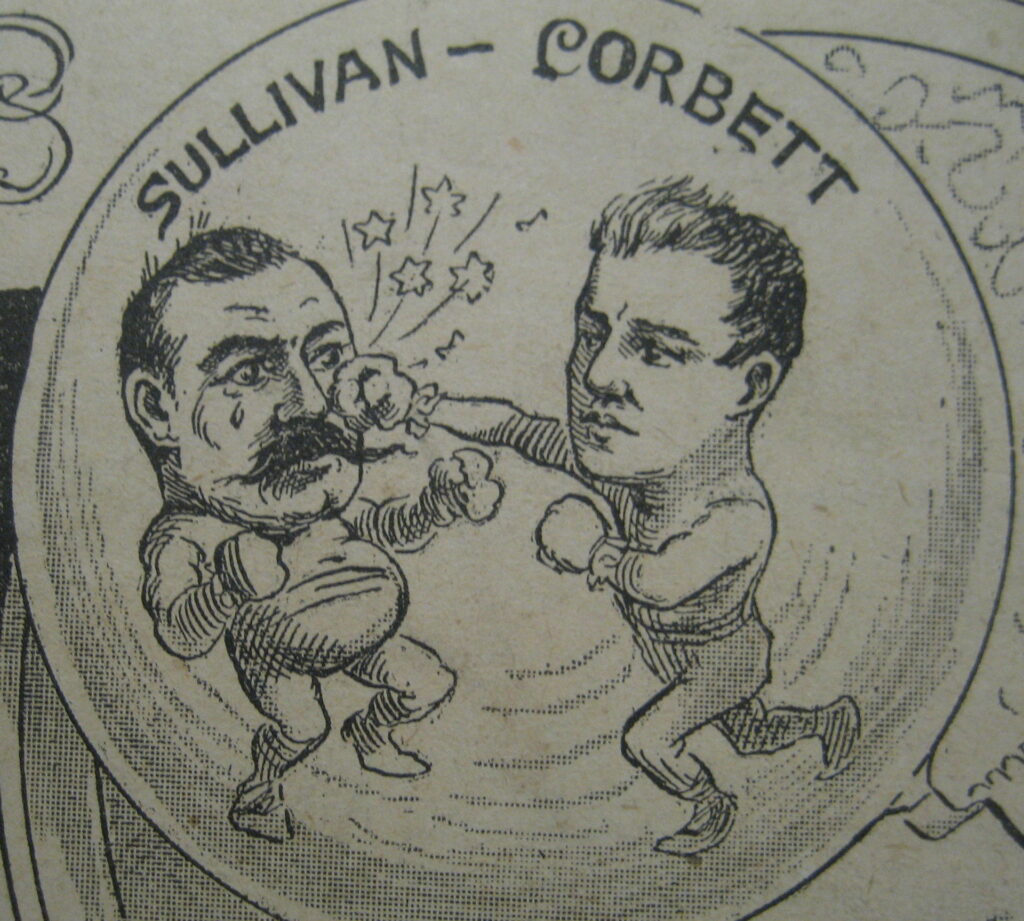

Jim Corbett KO21 John L. Sullivan, New Orleans, September 7, 1892.

This was the first heavyweight title fight under Marquess of Queensberry rules, with the contestants wearing boxing gloves. Sullivan’s famous wins had been in bare-knuckle fights under London Prize Ring rules. The famed Boston Strong Boy hadn’t had a serious fight in years. He had been touring the US in the stage production Honest Hearts and Willing Hands. Apparently his contract with the play’s producers stipulated that John L. was not to take part in a prize fight for two years.

The sporting public was growing impatient with Sullivan in effect sitting on the heavyweight title. “He had been enduring criticism for three years for not accepting challenges,” author Adam Pollack noted in his book In the Ring with James J. Corbett.

Sullivan accepted Corbett’s challenge for a purse of $25,000, according to Sullivan biographer Michael T. Isenberg, with a side bet of $10,000.

Corbett had just turned 26 while Sullivan was approaching his 34th birthday. A year earlier, Corbett had fought a 61-round draw (also recorded as a no contest) with the great black heavyweight Peter Jackson. The boxers wore five-ounce gloves in that bout. Corbett and Jackson basically fought each other to a standstill.

“Looked at from a scientific standpoint the battle will go down in the annals of the ring as the most remarkable ever fought between heavy-weights,” California’s The Morning Call newspaper reported. “Both men displayed wonderful quickness, and Corbett especially surprised everyone present, not only by his gameness, but by his cool judgment and generalship from start to finish.”

Meanwhile, Sullivan had boxed just once in five years, a three-round knockout win over a novice. He had been showing a fondness for drinking. The San Francisco Evening Post reported in a June 1891 article that during the course of a month spent in that city Sullivan “hardly drew a sober breath”, adding: “The time was spent in a long, uninterrupted debauch.”

So we had an inactive champion who had been leading an intemperate lifestyle against a younger, faster, more skilled challenger. Corbett’s manager, Diamond Jim Brady, had no doubts and apparently bet all the money he and Corbett had accumulated on an exhibition tour — some $3,000 — on Gentleman Jim to win at odds of 4-1 against.

Why was Sullivan installed as the favourite? Perhaps because the sporting types of the era felt that Corbett was too much a fancy dan and that Sullivan would be too powerful and too tough. Even the Morning Call, while praising Corbett’s performance in the bout with Peter Jackson, noted: “Corbett showed himself to be an exceptionally clever boxer, but those who watched him went away with a lurking suspicion that this far outshone his ability as a fighter.”

And there was, of course, Sullivan’s reputation — sportsmen of the era really did seem to view him as unbeatable.

Nevertheless, all the signs were there that Corbett would win. Corbett’s trainer, Billy Delaney, told the San Francisco Evening Bulletin that in all his years in boxing he had never been more confident that one of his boxers would win. Which Corbett did, on a knockout in the 21st round.

Jack Dempsey TKO end of 3 Jess Willard, Toledo, July 4, 1919.

It might seem unbelievable now, but Jess Willard was a 6-5 on favourite to beat Jack Dempsey. Willard was, of course, much the bigger man, standing 6ft 6½ ins and weighing 245 pounds to Dempsey’s 6ft 1ins and 187 pounds. However, Willard was 37 and had been inactive for more than three years while Dempsey, 24, was an active fighter who had knocked out five of his last six opponents.

Willard was talking about retirement. Looking back all those years, it seems that Dempsey was underrated because he had struggled with a boxer named “Fat” Willie Meehan in a series of four-round bouts (one win for Dempsey by decision, two decision wins for Meehan and two draws).

Also, there was the matter of hype. A heavyweight named Walter Monahan, who was one of Willard’s sparmates, told the International News Service: “That part of the public which is skeptical as to the ability of Willard to come back on July Fourth will be treated to a startling surprise. For it’s going to be a superhuman fighter, a Jess Willard wonderful beyond the wildest hopes of the champion’s most ardent admirers.”

“Superhuman fighter” — what a joke. Yet so-called boxing experts of the day were giving Willard a real chance. “Hundreds of thousands of dollars will be bet on the battle,” a writer named N.E. Brown wrote in a newspaper called The Morning Press. “It undoubtedly is the toughest heavyweight bout in history to size up in advance.”

As it turned out, the fight was a mismatch, with Willard knocked down seven times in the first of the scheduled 12-rounder and beaten up so badly that his corner retired him after three rounds. Willard’s age, inactivity, the fact that he had pondered retirement, were all pointers to Dempsey winning. At odds of about even money, Dempsey was a great bet.

Jack Johnson TKO14 Tommy Burns, Sydney, December 26, 1908.

Some odds in boxing history make one wish for a time machine. Odds such as Tommy Burns — the shortest heavyweight champ in history — somehow being made a narrow favourite by Australian bookmakers to beat Jack Johnson. “Had the fight been held in the United States the betting conditions would have been reversed,” the New York Times noted. Maybe so, but for Johnson vs Burns to have been anywhere close to even money now looks absurd.

Looking back at contemporary articles gives a clue to the odds being as close as they were. Observers of the day questioned Johnson’s heart. Burns himself was quoted as saying that in his opinion Johnson had a “yellow streak”.

Contracts for the fight were signed in London in September 1908. Burns was on a run of KO wins but he was just 5ft 7ins tall and would have been a light-heavyweight had he been boxing today. Johnson stood 6ft 1in and weighed a little over 190 pounds. There was no doubting Johnson’s confidence because when Burns left the US to box in London and Paris, Johnson travelled to Europe to issue challenges. When a fighter shows that much desire to box an opponent, it’s a pretty clear indicator that the fighter issuing challenges is very sure he will win.

and left with the heavyweight championship of the world.

Johnson hadn’t lost in more than three years. Despite Johnson’s advantages in size, the betting public was divided. “The public betting favors Burns at 5 to 4, and already a large amount has been put in the hands of stakeholders at these figures,” according to a pre-fight story from Australia published in the Sacramento Bee newspaper.

Burns’ obvious reluctance to face Johnson was telling. The sporting public of the time demanded the fight. Johnson argued that Burns had no right to draw what was then described as “the colour line” and the Sacramento Bee article noted that “no little amount of public opinion has sided with the black man”.

Finally, Burns agreed to terms. The Sydney promoters offered a purse of $35,000. Burns demanded $30,000, with $5,000 going to the challenger. It was a “take it or leave it” offer. Johnson took it. The bout was to be a “fight to the finish” but it was so one-sided that, the Associated Press reported, police at ringside ordered that the bout be stopped, with Burns “tottering and unable to defend himself”.

Officially, it was a points win for Johnson, the fighters’ camps having agreed beforehand that if police interfered the bout would be decided by a decision rendered on points by the referee. However, in reality it was a TKO win for Johnson.

The only possible reason Burns could have been favoured was a misconception that Johnson somehow lacked fighting spirit. But the wise guys who really understood boxing would have known that, in reality, Johnson vs Burns was a going to be a mismatch

“There was no fraction of a second in all the fourteen rounds that could be called Burns’,” novelist Jack London reported from ringside. “So far as damage is concerned, Burns never landed a blow.” People who bet on Burns were banking on him outgaming and outlasting the bigger man, and they got it totally wrong.