“The people who knew me best, they knew what happened in that fight. So, they all know that I risked a lot to win, and to put on a good show for the fans, always. I think, for that reason, it was worth doing.”

You’d be forgiven for thinking ‘it’ was damaged hands, trembling under the slightest pressure of a friendly handshake; or a slanted, crooked nose, telling stories of difficult nights through obstructed breaths. Maybe ‘it’ was bankruptcy, criminal charges, or a failed marriage after repeatedly dedicating weeks to brutal training camps that resulted in defeat and depression.

In fact, Israel ‘Magnifico’ Vázquez (44-5, 32 KOs) was detailing his life after losing all sight in his right eye, the result of sustaining multiple injuries to his retina which required various, desperate surgeries. Boxing – for all of its success stories and its few inflated bank accounts – always outlasts its plucky challengers. It is the only real winner.

Vázquez was notoriously one of the toughest fighters of his generation, but when talking to Boxing Social, he explained it had to be that way to gate-crash the history books: “They took notice [because of my style], yes. Maybe if I hadn’t had those wars in front of the great fighters I faced, maybe we wouldn’t be doing this interview. Because, apart from being world champion, I also wanted to leave a mark on the sport. I didn’t have this great amateur career, you know.

“I wouldn’t change anything about my past as a boxer. So that I could achieve what I wanted, with effort, dedication, and discipline, I had to fight like this. I liked that counterpunching, backfoot style, like [Ricardo] Finito Lopez, Juan Manuel Márquez or Floyd Mayweather. But they were unique cases that people still remember. Today, many fighters with that style are not praised very often or spoken about by fans.”

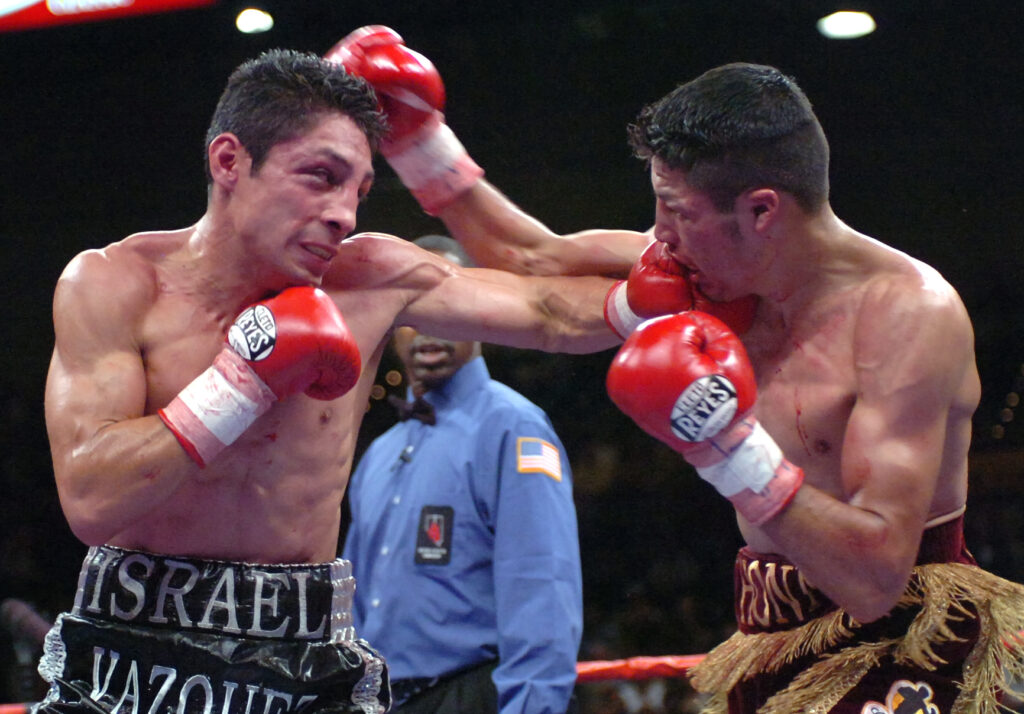

Vázquez is regularly mentioned however, for his legacy-defining four-fight series with fellow Mexican Rafael Marquez, his triple-header with Oscar Larios, his three stints as world super-bantamweight champion, and his eyes.

Photo: WBC.

He was fearless between the ropes during his prime, but explained his introduction to boxing as a frenetic kid in Mexico City started a journey that even he hadn’t expected: “My intention in life was to have a university degree, but things changed when I started to see my potential inside the boxing ring. I wanted to study law, but by the time the exam came, I had already made my professional debut [aged 17].

“I always liked to compete and I was just a restless kid,” the father of three told Boxing Social. “So, I said to my dad, Valentin, that I wanted to box. And finally, he took me to the Margarita Gym, with Don Guadalupe Serrano. I was just a spectator at first, but while watching my brother German practice, I went over everything that he was taught in my mind. When we got home, I would try it for myself without anyone noticing, so I knew how to throw the basic punches without formally attending a boxing gym.

“A few months later, I signed up. When I started hitting bags and mitts, I always tried to do it perfectly. My thought was: ‘If for some reason someone corrects you more than three times, it is because that activity is not for you; find an alternative. Give your best and die trying with your head held high’. I finally went up to spar at the gym. The opponent was the same age as me, but with a few years of additional experience. He had no compassion and [I can remember] he hit me really hard.

“My father told me that day that I’d better find something else. I knew, considering it was my first time sparring in the ring, that it wasn’t such a bad performance. I made it my short-term goal to be like that guy. And every weekend when we sparred, I found myself noticing an improvement. Until one day, he made excuses to avoid getting into the ring with me. That’s how I started sparring with people older than me. I even helped several world champions like Humberto ‘Chiquita’ Gonzalez [WBC champion at 108lbs and 112lbs] and Julio Cesar ‘Navajo’ Borboa [WBO champion at 112lbs].

Vázquez and his family weren’t blessed with fortunes and boxing would dangle a carrot in front of the 17-year-old university hopeful, allowing him the opportunity to earn fast cash, helping to put food on the table. They lived in a spare side-room at his father’s place of work back then, which was far from a normal residential space: “I didn’t have a house formally; they were just rooms that were attached to the building. My dad worked – and we actually lived – in a funeral home.

“We had shortages back then, in terms of housing and clothing. But luckily, we never lacked food. I usually just wore the clothes of my older brother, German. Although he is three years older than me, there came a time where between six or seven-years old, I could fit into his clothes. Then I worked from the age of nine in a shopping centre, packing people’s purchases and they would tip me. I worked in a mill, where people in Mexico would grind up spices, and that was my job at Christmas time.”

Vázquez continued, detailing the decision to focus on a career in boxing: “I was in high school at this time and I decided to make my professional debut, since nobody wanted to fight me as an amateur. I made my debut in a tournament called the ‘Gold Belt’ [held in 1995].”

A teenage ‘Magnifico’ was thrust into the tournament, squaring off against more experienced professionals and setting a precedent from the opening bell of a thrilling, successful career. He fought Eduardo Rosas (WTKO1) in the opener and made short work of his 2-0 opponent. Rosas would draw his next two fights and win his final two before bowing out; club fights and fighters in Mexico seem to follow their own, peculiar narrative.

“The competition was the first of its kind at a professional level, it was endorsed by the WBC. I entered at short notice because one of the fighters was unable to attend,” said Vázquez. “They notified me just 10 days in advance, but despite that I made my debut with a win in the first round. And two fights later, I became champion of that 118lbs tournament and my name stood out a lot. I was the winner of the ‘Gold Belt’ – and I was only 17.”

Vázquez averaged a fight every two months for the first year-and-a -half, winning all of them before crashing into Ulises Flores (L TKO1), who was a well-travelled test for promising prospects. He caught Israel cold – but the future world champion was back to winning ways just a month later, kickstarting a run of 11 consecutive wins including a first-round stoppage victory over Oscar Larios, who was the proud owner of a 20-0 record at the time.

“I never ‘imagined’ getting anywhere because I think that would have frustrated my goal,” he said. “I simply trained hard, and the results were taking me closer to achieving it. Step-by-step, I managed to become a name in my native country of Mexico. The name ‘Vázquez’ was in newspapers and featured in some television interviews, and I saw the possibility of one day being crowned champion: it kept moving closer.

“My first title was the ‘Gold Belt,’ and later some titles at the local level. I became the NABF champion; now that was a title that placed you highly in the world rankings. But until the world title opportunity came through the IBF [I just stayed focused]. I always thought about fighting, in the ring when I sparred, or even outside of the ring. Unless I had a fight on my own doorstep, I acted like a professional every step of the way.”

He would have the chance to realise that goal in March 2004, standing opposite Jose Luis Valbuena in Los Angeles’ Grand Olympic Auditorium, ready to contest the IBF’s vacant super-bantamweight crown. Valbuena, hailing from Venezuela, was missing a marquee victory on his own record and it never came that spring evening. Vázquez announced himself that evening, winning by TKO in the last round and thrusting his world title belt skyward.

Photo: J.P. Yim/Zuma Press/PA Images.

The proud Mexican had suffered three defeats at that point in time, losing his rematch to Larios in 2002, and dropping a split-decision to the unfancied Marcos Licona. Boxing had started to wear parts of him down physically, yet Vázquez knew he still had more to sacrifice. Making it to the top wasn’t easy by any means, but staying there was a whole different ball game.

Then-champion, he embarked on a string of fights that emotionally exhausted fans. He defended his belt twice, before abandoning the IBF title and taking on Oscar Larios once again in their rubber match. Vázquez emerged victorious, capturing the WBC bauble, and stopping his old foe, and he proceeded to fight Ivan Hernandez, Jhonny Gonzalez and Rafael Marquez (three times) over the next 21 months.

It was a cruel, punishing schedule and plenty of blood was spilt. But it had to be. It’s what defines him, even now a decade into retirement.

Following his third bout with Marquez – and after suffering a detached retina in his right eye, with bulbous, plum swelling – Vázquez required surgery. He spent 2009 recuperating and, while he thought lovingly about his return to boxing, many prayed he’d walk away. There were articles published expressing concern for his physical well-being and particularly for the functionality of that right eye. But he couldn’t go back to the grocery store or the spice mill; he couldn’t sit his university exam then.

Vázquez’s career succumbed to an eye injury. Photo: WBC.

So, he returned, facing Marquez for a fourth time, and subsequently ending his own professional career. Reports of Vázquez, now 43-years old, having his eye removed surfaced in 2016 after the nerves stopped working altogether. The news washed over boxing’s ardent fanbase, causing members of the media to question the sport’s safety.

“With my eye damage, I consider it an accident. I thought, ‘This injury could have [happened] in a car accident, or when I fell from the shower in the bathroom.’ The people who knew me best, knew what happened in that fight. So, they all know that I risked a lot to win, and to put on a good show for the fans, always. The truth is that time has passed quickly since my last fight in 2010. But I still remember boxing fondly.

“See, I am lucky that I don’t go through that [depression after retirement],” Vázquez explained, gratefully. “I still miss a lot of things, like the adrenaline rush before a fight, the sweat dripping down my face after finishing a workout. Many things. But I resigned myself to retirement. My family was an important factor, so my retirement wasn’t so painful. During my fighting career, I concentrated at home, but mentally I was focused on the fight. You know how much it takes to get to 100% or to put on a good show. Now I can focus on my family and my children, making sure they are good examples.”

When asked how he’d feel about his own children entering the ring, Vázquez remained pragmatic: “My children have decided not to dedicate themselves to boxing. The oldest plays soccer, the middle one doesn’t play any sport and, well, my youngest daughter likes boxing a little bit. I teach her some things now and then. And without a doubt, I would support her in everything she wants to do, it’s the same for all my children. At least I know that I tried to set a good example for them.”

His description of violence and serious injury for the entertainment of others was startling and delivered with a gentle shrug of the shoulders. Trying to run his ‘Magnifico’ Boxing Gym while battling a recently diagnosed autoimmune disorder (only discovered with the assistance and support of the WBC President Mauricio Sulaimán) and trying to maintain a sense of normality after sacrificing his senses for boxing, Vázquez still insists it was worth doing.

It is that unbreakable spirit that fighters chase and it’s that stubborn bravery that terrifies the sport’s governing bodies and commissions. Vázquez, struggling with his own health and living frugally from month-to-month, left his mark on boxing. It’s easy to ask, ‘At what cost?’ but it’s too late for that. And he’d do it all over again.

Main image: J.P. Yim/Zuma Press/PA Images.