There are endless ‘what if’ stories in boxing. There are numerous tales of fighters turning around their lives from a criminal past. Boxing has many redemption stories, the sport has undoubtedly saved many.

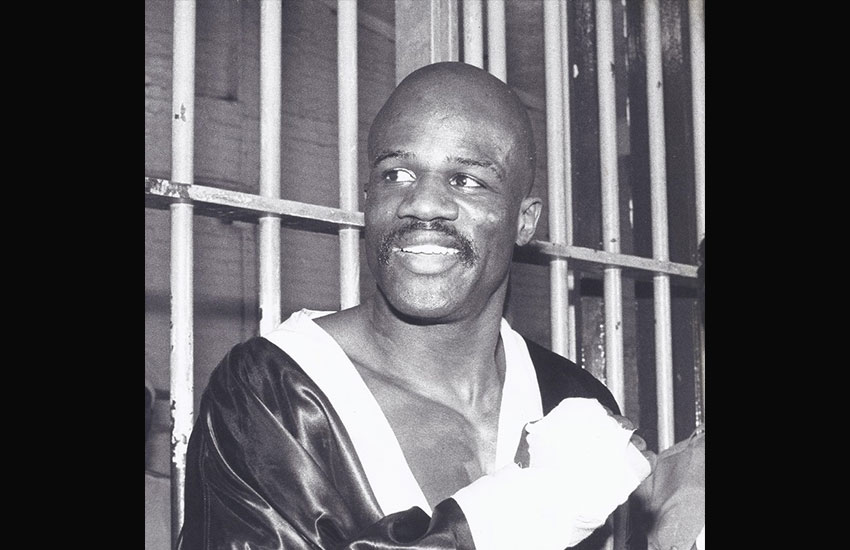

But it can’t save everyone, and maybe one of the biggest ‘what could have been’ stories is that of former light-heavyweight contender James Scott.

Scott could have been a world champion, and that is no false claim, even at a time when his division was at its strongest in its long history. Make no mistake, Scott was some talent.

Born in a Newark ghetto, a life of crime was perhaps inevitable; he admitted he was attracted by the gang way of life. The numerous stints in prison that followed stopped the American from realising his potential as a prizefighter.

Scott first encountered prison life when he was just 13 and in 1965, aged just 18, he was residing in state prison, but his new home had a boxing program. Scott showed potential, but after his release in 1968, he couldn’t stay out of trouble. After a further conviction, this time for robbery, he found himself in Rahway State Prison in New Jersey.

But Scott continued to box whilst inside, as state prison champion, becoming so feared few would challenge him. When he was released in 1974, Scott turned professional. Only a draw spoilt his early 11-fight record, where low blows cost him the win, and Scott looked as though he was about to become another success story for the sport. There was talk of fights with John Conteh and Bob Foster, his future seemed laced with world titles, but his past would soon return.

Maybe inevitably, Scott, soon found himself back in Rahway. Involved in a violent robbery in which one man, Everett Russ, lost his life. As a multiple offender, this time his stay would be much longer. A charge of murder wasn’t proven, but a 30-40 year sentence was still handed down.

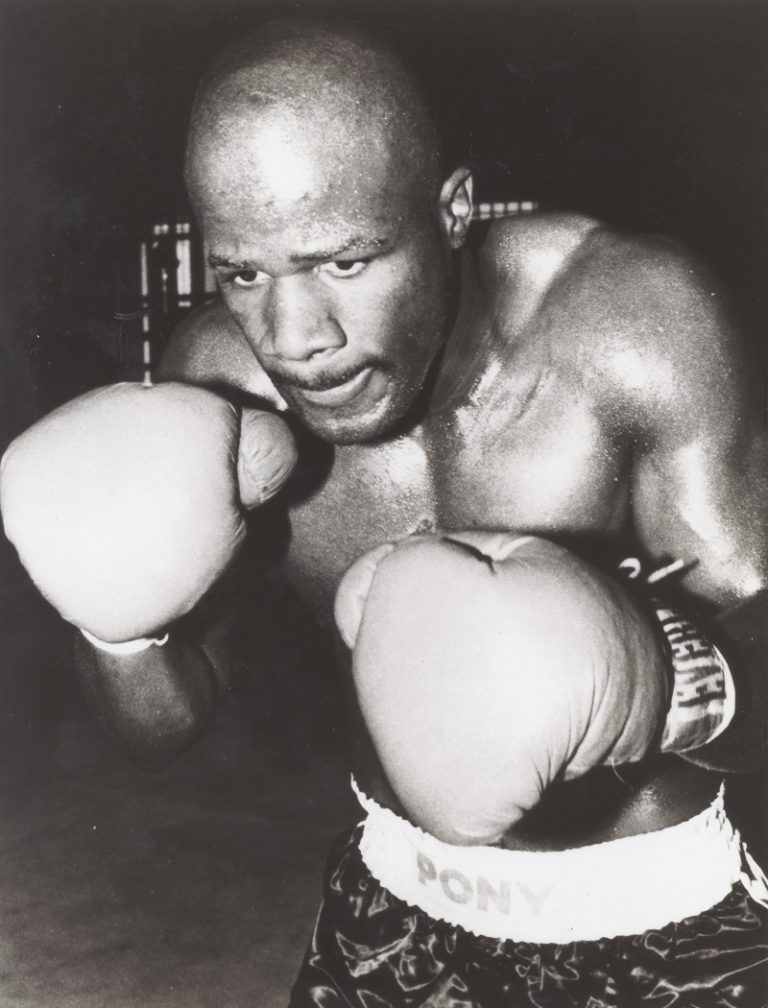

However, his boxing career eventually continued in 1978, with the help of prison warden Robert S. Hatrak. New promoter Murad Muhammad somehow funded fights and found a way for the inmate to box professionally again despite being incarcerated in a state prison. Hatrak believed in redemption and resurrection, and Scott had a lifeline.

in the world whilst serving time in Rahway Prison.

HBO was looking to establish its sporting presence in 1978 and, with the WBA deeming Scott worthy of a world ranking, an unlikely alliance was formed.

After a couple of low level wins, the WBA’s top contender Eddie Gregory, who would later change his name to Eddie Mustafa Muhammad, was tempted to face Scott, then HBO entered the fray.

With a record of 12-0-1, 6 KOs, Scott was deemed little more than a curiosity. Gregory was on the verge of a title shot against then-champion Mike Rossman and appeared to enter the prison walls seeing little threat. Gregory had served time himself and he called it a homecoming; it was anything but.

Gregory was 1/4 to win, even the prison betting line had him the likely victor. But Scott showed the rich potential he had, dominating and battering his more favoured opponent, winning a clear unanimous decision.

From being nothing more than a fascination, Scott suddenly hit the headlines, even calling for a fight with Rossman himself. Harold Lederman, who witnessed the Gregory fight from ringside, called Scott ‘the best light-heavyweight he had ever seen’.

Four more victories followed the upset win over Gregory, solid opposition like Richie Kates (WTKO10) and Bunny Johnson (WRTD7) left the prison grounds empty-handed, but Rossman couldn’t be tempted to fight Scott.

The WBA world title would become vacant, yet Scott was already scheduled to fight the new No.1 contender Yaqui Lopez.

But hopes of Scott contesting the vacant crown were dashed by politics. Scott and Lopez still traded blows, the prisoner won a decision and, in many ways, he was now the uncrowned champion.

But that was as good as it got for Scott. The WBA had second thoughts about having a convicted felon in their rankings and, in 1979, his No.2 ranking was gone, his fate decided in a smoky room somewhere. Hatrak would soon be removed from his position and that left Scott treading water, his peak and his hopes slipping away.

Scott took on fellow contender Jerry Martin in 1980 and the dream would soon be over. Dropped in the first and again in the second, Scott survived but would eventually lose a decision.

The following year, Scott was retried for the murder of Russ and this time the jury reached a guilty verdict and he was sentenced to life.

In the same year, Dwight Braxton (later known as Dwight Muhammad Qawi) ended any lingering hopes of a title shot or anything else. In his seventh televised fight, while serving his sentence, Scott dropped a 10-round unanimous decision and the door slammed shut for a final time on his boxing career.

The Braxton loss signalled the end, the TV cameras didn’t return and neither did Scott. That was his last contest and he left the sport with a record of 19-2-1, 10 KOs. The fight finally left his body, a fading fighter, a fading man.

The American prison system is one of survival rather than rehabilitation. Scott tried to escape it in different ways. Appeals led to nothing, attempts to fight outside of the prison walls ended without success. The voices of resentment grew louder and Scott found he had no way out, nowhere to go, the story of his life.

A life inside started with truancy before his troubled teenage years set the tone for his adult life. Scott spent much of his existence locked up and probably deserves little sympathy for his plight. But he had genuine talent inside a boxing ring and, for a time, he had a glimmer of light in his life, in a place where the darkness allowed very little hope.

Maybe what happened in Rahway was a different form of punishment. Scott was shown a life he could have had, one of a world champion. Just when it seemed probable, agonisingly close at one stage, it disappeared when it was seemingly there for the taking. Without boxing and the TV lights, Scott faded into obscurity, back to serving his time in more conventional ways, the way the system demanded.

Scott was finally released in 2005 after being behind bars for 28 years. He suffered from dementia in the later years of his life and died in a nursing home in 2018. Scott was inducted into the New Jersey Boxing Hall of Fame in 2012, an honour barely touching what he should and could have achieved.