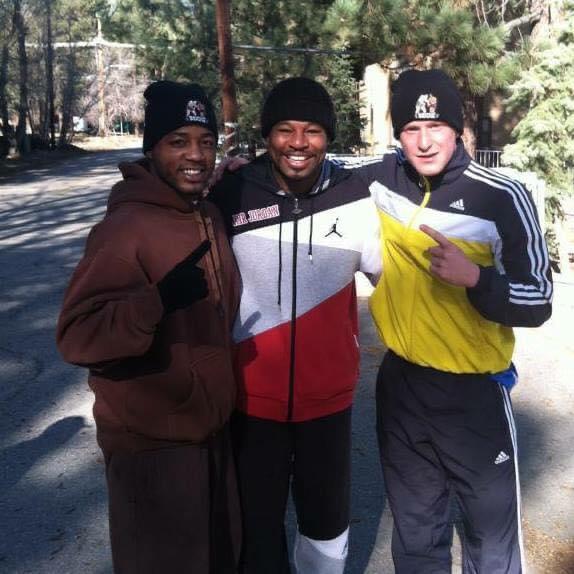

“I remember the first time I smoked heroin; I went missing for three months. I went up to Big Bear on a camp with [Shane] Mosley for eight weeks, and I was trying to get a hit up there, but it is a really small city about 80,000 feet up.”

Edinburgh-born boxer Jamie Robinson (2-0, 2 KOs) is desperate to complete his return to the ring this March, but his torrid journey through homelessness, drug addiction and morbid depression has threatened his remaining aspirations…

Boxing has always been synonymous with mysterious characters, flitting in and out of the sport’s full beam, blurring the line between fact and fiction. For every humble, honest fighter on the straight-and-narrow, making steady progress, there are schools of men, shadow boxing in pursuit of dreams long forgotten, tangled up in darkness and despair.

Tracking down Robinson had happened purely by chance after stumbling upon his Instagram page, which was mentioned during casual conversation; and just nine months after driving for two long, continuous days from the America’s West Coast to his current residence in Miami, he was determined to finally reintroduce himself to boxing fans and fulfil his potential.

“It’s just been fucking crazy,” started Jamie – or Jay, as he’s known – recalling his introduction to boxing. “I was all over the place. I grew up in Edinburgh, and I had a decent wee life, but I just ended up always getting myself in trouble. You know yourself, in Scotland it’s so easy to get into trouble. I was on and off [boxing] from a very young age. I was in the gym for six months; I’d have three or four amateur fights and then I’d go off again on the drink or whatever I was doing. I was in Edinburgh until I was 15 and then I ran away to London.

“I got myself involved in selling drugs in Edinburgh. Not at a very high level, but just being involved with fucking idiots. It’s the story of my life. I was dealing drugs and had like 2oz of weed on me; I was dropping it off to a guy that was gonna deal for me. I came around the corner and the police stopped me. I thought, ‘I need to get away from all of this’. Two or three days after that, I said to myself, ‘Okay – I’m going to London. I’m gonna be a boxer’. I had no connections at all, I just showed up.”

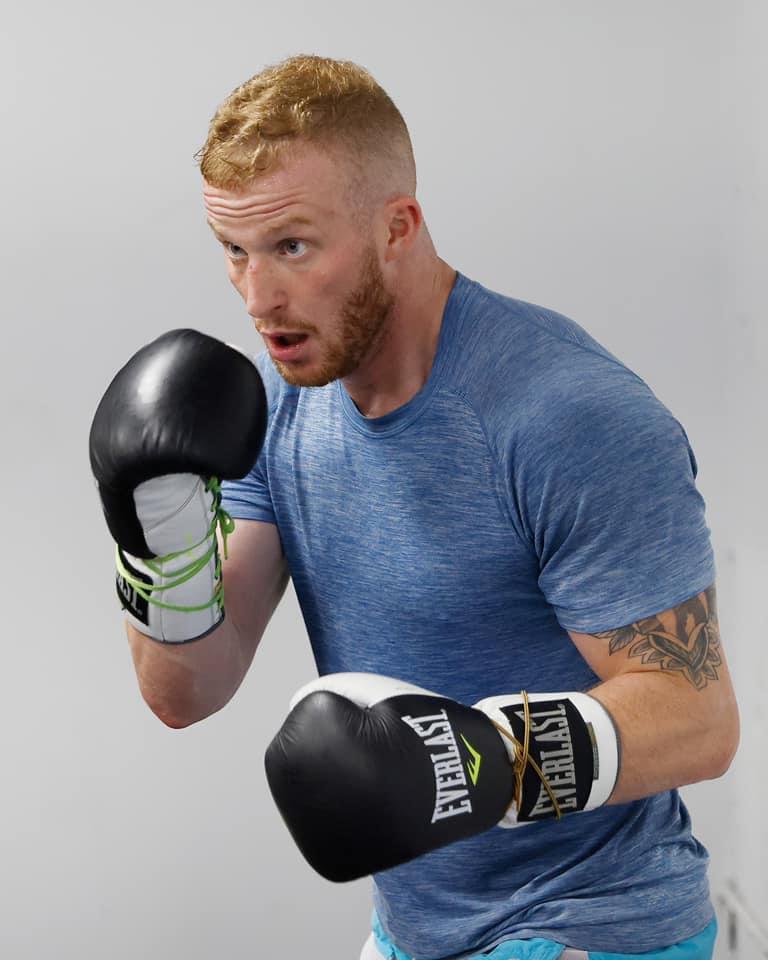

Photo: Hybrid Performance Method.

Something that became clear throughout our conversation was the 29-year old’s propensity to ‘just show up’. He has swaggered into the Peacock and TKO Gyms, both in London; then flown over to Los Angeles on a whim and chanced his arm at Freddie Roach’s Wild Card Gym; before finally entering Miami’s 5th Street Gym in search of redemption under famed Cuban coach, Jorge Rubio.

Robinson certainly doesn’t lack credence – and he tells a hell of a story, aware of his own gift as a ‘talker’. Piecing together the early career of the unbeaten professional was like attempting to complete an enormous jigsaw with less than half of its pieces. The pieces we do have, however, are full of colour and Hollywood characters, and make for excellent copy. But there is plenty of darkness in the lost years.

Living in London wasn’t quite enough for the young Scot, who spent time sleeping on the floors of the gyms he trained in, wearing clothes that had been left behind or discarded by fellow fighters. Selling drugs was an easy option and allowed Robinson the chance to save face, earning money and standing on his own two feet. I spoke to former professional Frankie Monkhouse, who remembered hosting Robinson one Christmas Dinner with his family; two Scots chasing different dreams in the big city.

“I have bipolar, so I’ve been dealing with that,” explained Robinson, when discussing some of his erratic and dangerous behaviour pre-diagnosis. “It’s a lot better now and it’s under control, but back then, you know, the highs were just fucking awesome; I’d be making decent money from personal training or doing whatever I had to do. I was dealing drugs a bit on the side; I got myself involved in some heavy, serious stuff. It was about four or five grand a deal; I thought I was Don Corleone.

“I saw myself going down the same path again, getting into trouble. So, at 17, I thought, ‘Fuck it – I’m gonna go to America’. I just showed up at the Wild Card Gym after making a few deals; I think I had about 15 grand and I flew to LA; no visa, no nothing, and just said, ‘I’m gonna be a world champion’. They were like, ‘Do you have your paperwork?’ I didn’t have any of it. I just remember thinking, ‘I’ve got no idea what I’m doing with my life – but I’m living the dream’.

“I basically became a sparring partner for money. I sparred every cunt at the time. Everyone. Shane Mosley, Manny Pacquiao, Denis Shafikov, Jamie Kavanagh, just everybody. I’d get $50 per round and that’s what paid for my motel. I was at a motel in Carson – $30 per night, but it had a pay by the hour option. I used that money to start a gardening business. I built that up, and then got married, had a kid, had a couple of fights. Things were good.”

He pauses, giving me the indication the weather is suddenly changing: “And that’s when things went off the deep end…

His two professional fights came almost seven years ago, with each opponent the proud owner of a 0-1 record. The bouts were staged in Mexico, in what looked like a factory, fenced off and surrounded by dusty car parking spaces. It was actually one of Tijuana’s premier rooster fighting arenas, and Robinson loved every minute of it. He stopped both men impressively, with neither seeing the third round.

Photo: Jamie Robinson.

Those contests are listed on BoxRec, with the last taking place over 2,350 days ago, but there’s very little else for research purposes. The Edinburgh-native had slipped through British boxing’s net, with only a single blog post on a website called britsinLA. That was a Q&A, designed to link like-minded Brits in California, and his post was published just a few weeks ahead of his last professional outing.

On the website, Robinson gives the following advice: “Have some extra money to use because you will need it. LA is expensive place! I made the mistake of doing nothing – [coming here with no] money.”

“I was back training straight after that second fight. Everything was good. But then I met a guy that was heavily involved in drugs. Boxing and that kind of world are always involved with each other, you know? As usual, he flashed a bit of money at me and he was saying ‘I can get you $20k for this, just drive a car here, do that’. Being a married man in Suburban LA, selling drugs like that with a kid, it’s a recipe for divorce.

“Once you start involving yourself in that life, you’re out partying in Hollywood, you start thinking you’re the man, and you start using drugs. Training takes a backwards step, so instead of going to the gym, I’m out at clubs all night. It doesn’t ever end well. I’ve got an addictive personality, so I started dealing heavier drugs and it was a very fast, downward spiral once it started. It was people who spent 20 grand on a night; it was ridiculous money.

“I saw it as a quick and easy way of going from a wannabe boxer who was just doing okay, to somebody who could really make a name for himself. I just, well, I thought I was a gangster. That was it,” he concludes, with a noticeable dip in his tone.

The blue-eyed Jamie Robinson that packed up and left Scotland for the excitement of London or Los Angeles would have worshipped the Hollywood drug dealers he’d end up working for. But now he understands that life can be snatched away, and time doesn’t wait for men to serve their sentences; it moves on – and quickly. He’s a different man now; I think I stand by that conviction, knowing little else.

“I was selling drugs on a lower level, so I was going to drop drugs off in East LA, or I was going to crack dens or going to peoples’ houses in the Hollywood Hills. I started smoking weed, and that was really addictive; I’d wake up in the morning and smoke weed first thing, so I’d be high all day. That turned into doing cocaine to get me through my day at work. Then, that progressed into taking heroin. I thought, ‘The weed isn’t really doing it anymore,’ so, I started, well, I started smoking heroin.

“Time doesn’t exist. Time isn’t even a thing; it just stops. In my head, I was this bad ass boxer and I wanted to cling onto that. I’d show up to the gym for two months at a time, but I wasn’t being honest; I wasn’t being truthful with who I was. I’d train for a week, but I’d miss the partying and the drugs, so the weekend would be nuts, and then I’d get back to the gym again. I was a mess. I almost get teary-eyed thinking about it. It was just nuts. It was this fucking vicious cycle because now I’m addicted to drugs; my marriage has fallen apart because I’m a junkie; and my boxing career is gone.”

Photo: Hybrid Performance Method.

It took an altercation with his then-partner and now close friend – which resulted in the cops arresting Robinson after he falsely claimed she had a gun – to shock him back to his senses. He knew he had to make a dramatic change, so he packed a small bag and hit the road. Robinson never really had a desired location in mind, though he admitted that Vegas would have killed him, and that New York was too expensive.

Two days of almost constant driving, plenty of head space and an unhealthy amount of caffeine later, he parked up in Miami, Florida. Just showed up, he tells me.

That was nine months ago and now, just weeks from his eventual third professional fight, he knows just how lucky he is: “I’ve had to do a hell of a lot of work on myself, and it’s always gonna be a work in progress, trying to be a better person, or in business and life. I deal with bipolar, like I said, so I have to try and deal with things consistently, so that I can minimise the highs and the lows. I struggled to accept it; I felt like a wee bit of an outsider. But the more open I’ve been about it, the more people have come to me to speak about their own issues, and I like that I can help anybody that needs it.

“Everything is signed for the fight; I’m fighting Luis Marquez, a local kid from Nebraska, and I’m hoping he’s coming to fight so we can go at it. I’m definitely gonna get teary when I make the walk; it is surreal, but the closer it gets, the better I feel about it. I’m just a wee guy from Scotland who lived in crack dens and sparred the best in the world. Boxing is all I know – I just want to show people that you can fuck up majorly and do something with your life. It’s okay to talk about it.

“I’ve got this unbelievable team for training now, I’ve got a 26-time world record holder for strength and conditioning and Jorge Rubio, a trainer of multiple world champions. It’s got to happen for me now. There’s no reason I can’t do it. I must win, otherwise the next stage of my life can’t happen the way I’m planning it. It’s gonna be great just to get back in there but winning is everything to me. It’s always felt that way.”

Photo: Jamie Robinson.

Robinson has crammed a lot of living into his 29 years, and he’ll have to hope that time slows down as he marches towards meaningful fights. His training looks relentless; he is constantly running, lifting, punching or skipping. His sparring is completed under the watchful eye of Rubio, and he has signed a deal with First Round Management, with all parties determined to make a success of his rebirth.

His health and his recovery from drug addiction are shining lights for aspiring fighters who have suffered similar trips, slips and falls. The truth remains that we don’t really know how good Robinson is. But he is trying to live in the here and now, and to make the most of his second (maybe third, fourth or last) chance properly.

“I want something to put on my mantelpiece. I just want something to prove that I did it. I’ll take the Florida Wrestling Championship! I just want some type of belt, to show that you can make something of yourself. I have a lot of remorse and regret about things that I’ve done, or about people I’ve fucked over. I don’t ever want to be that guy again. I want to be a positive influence on the people around me and within society. You can change – that’s what motivates me.”

Boxing allows guys like Robinson to work in silence – or to disappear completely – battling issues that are bubbling beneath the surface, so who are we to doubt them on their return? You can discount his chances of appearing at an elite level within the sport given his age and inexperience, but you never know, he has a habit of just showing up.

Photo: Jamie Robinson.

Main image: Photo Hybrid Performance Method.