The tree that’s inked onto the chest of Kali Reis – a lonely alien sprouting healthy branches and boasting strong, dark roots – is a symbol of growth. The tattoos that race up and down the Rhode Island-native’s chiselled arms tell tales of torment and triumph; while the metal studs that pierce her cheeks are a nod to her Native American culture.

Reis comes from fighting blood and, as a proud descendant of the Wampanoag tribe, she greets you with a “Chuh” or “Hey”. Boxing commentary blares in the distance, producing a constant backing track between her laughs, thoughts and things best left forgotten.

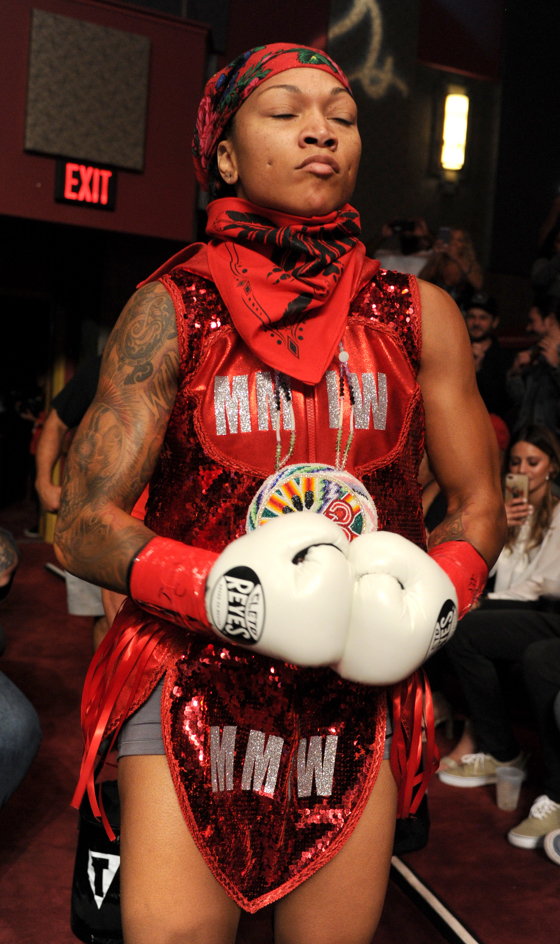

She was recently pictured with a red hand painted across her face, paying tribute to the powerful ‘Murdered and Missing Indigenous Women’ (MMIW) movement.

Life is much bigger than boxing for ‘KO Mequinonoag’: the actor, former bouncer and security guard, mentor, motivational speaker and qualified motorcycle mechanic. It’s the protection of vulnerable women and the sanctity of her depleted culture, pillaged over generations.

Her career between the ropes – emerging from the Estrada family’s Big Six Boxing Academy in Providence – includes two world title successes and bouts opposite some of the sport’s biggest names, such as Cecilia Braekhus, Hanna Gabriels and Christina Hammer. Based in Philadelphia, the WBA’s new super-lightweight world champion, has a story that the most intriguing fighters, regardless of gender, simply can’t match.

After regaining a portion of a world title competing 20lbs lighter than her first success, it’s time for Reis (17-7-1, 5 KOs) to share her story in its entirety. And when talking to Boxing Social she reaffirmed her desire to dominate at 140lbs after suffering a particularly tough, recent spell: “I almost hung them up a few times. I just felt as though I wasn’t getting what I wanted and I have a lot more going on outside of boxing.

“It feels amazing to be a world champion again. And it’s in a weight class I never thought I’d get down to, so I’m in a really good position now. The experience I’ve had as a professional at this level for so long, and still being highly relevant in a weight class where I’m not just some road warrior-type veteran; I’m in my prime and things are just going to get better from here. There was a little bit of light back then… but now, there’s a lot more at the end of the tunnel, that’s for sure. I know that 2020 was crazy for everybody, but for me personally, it hit me quite hard in some ways.”

We don’t mention it; but the passing of her father, musician Flinky Reis, signalled the beginning of a darker autumn.

Kali’s heritage is mixed, half-Native and half-Cape Verdean, but she’d never quite settled with either group entirely, explaining she was, “never Native enough and never black enough. Just the skinny, light-skinned girl”. Growing up in Providence wasn’t easy and turning to vices at a strikingly young age would lead to confusion and pain left hanging over her adolescence, like unpaid debts.

“I don’t come from a family of fighters – I’m the oddball. I was artistic, I was always into something and being Native American-Cape Verdean, my mum raised me deep in our culture,” she said. “I didn’t grow up in Bel-Air, you know, but it wasn’t Compton either. We were well-off sometimes and then other times we weren’t. My parents got divorced when I was really young, age four or five, so my father was in-and-out my whole life. I was just that younger kid, being bi-racial, being unsure of my sexual identity, I couldn’t really find where I belonged. It was tough.

“Natives have this idea of hair being poker-straight, so then I’d have my mum straightening it out before Powwow competitions, just to make sure that nobody made fun of me and called me the ‘black girl’. I got comfortable being uncomfortable at a young age. I had to turn inward to myself; I didn’t have anybody I could talk to or trust when I was going through my own struggles.

“There were so many things I had to worry about,” Reis admits, bravely. “I started smoking weed when I was 11, then aged 12 I was raped by a neighbourhood kid that I thought I trusted. So, I was drinking when I was 12-years old and there was a lot of things from the age of 10 to 13 that really threw me off. When I was boxing, that was the only time I didn’t think about everything else. I paid attention – I’m a big sponge anyway, but I liked how quiet my mind would get in the chaos of boxing. The gym felt exactly like where I wanted to be.”

Formed in the shadows of American contender Peter Manfredo Jr. and Olympic hopeful, Jason Estrada, the Big Six was the safest place for Reis. She would study boxing under the watchful eye of Dr. Rolando Estrada (Jason’s father) and Peter Manfredo Sr. and, despite never being the team’s priority as a professional fighter, she was always made to feel welcome, and loved.

“There was a lot of people I was around; Vinny Paz, as crazy as he is, I was always around guys like that. Peter Manfredo Sr. Peter Manfredo Jr, Matt Godfrey, Jason Estrada. I just watched and learned; how this one moves, how that one moves, what’s good and what’s bad. If I didn’t know, I just learned through experience. ‘Okay, that was a bad negotiation, I could have got a lot more that fight!’ But I know now.”

Reis, now 34, continued, “I always knew I was destined to do something way out of the norm, it just took me a while to understand that. I don’t know who says they find their journey through boxing easy, but I never got anything handed to me. My first world title fight at middleweight was self-made, I didn’t have a promoter or a manager. I scratched and clawed my way up to the top. I didn’t believe in myself; I didn’t think that I was worthy of it at first. But I didn’t want to be a big fish in a little pond or have that mentality; that’s not in my blood whatsoever.

“I want to fight. I’ll be sparring guys and I always learned the most when I got my ass kicked. I wanted to know, ‘What happened? Why did that happen?’ I didn’t wanna beat up on a new girl and build false confidence. My goal was to fight the best and to see how capable I could be or how good I could be. Even today, sparring better fighters than me, I always want to learn. That’s always been my mindset. It was learning on the job, skill-wise and business-wise. I wouldn’t have it any other way.”

Early professional bouts should have resulted in routine victories, but with women’s boxing divisions lacking depth, Reis found herself facing better opposition early. After four fights, her record was 2-1-1, but stubbornly, she wouldn’t be deterred. In fact, after her first 10 fights as a paid boxer, she’d already watched her opponent’s hand raised on three occasions.

Losing shouldn’t define fighters and Reis explained that, despite feeling “pissed off”, she promised herself continuous improvement at every outing.

She faced Teresa Perozzi (WTKO3) in November 2014, for the lightly regarded IBA world title, in Southampton, Bermuda, and a blistering victory changed the career trajectory of Wampanoag’s fighting pride. It was this win – despite her coach suffering a heart attack just days from the fight – that placed Reis in the clutches of the division’s biggest names. Again, she’d find comfort in the uncomfortable.

A pair of unanimous decision losses to Christina Hammer and Hanna Gabriels occupied 2015 for the Rhode Island fighter, suffering competitive defeats against certified champions. That big night wasn’t too far away, however, as Reis would fight Golden Boy’s Maricela Cornejo for the vacant 160lbs WBC world title, winning by split-decision. Almost overnight, she became something of a priority, commanding the respect of the boxing public and preparing to run another gauntlet that included Hammer (L10) and undisputed welterweight champion, Cecilia Braekhus (L10).

“It didn’t always feel achievable. I had people telling me constantly who I wasn’t supposed to be and what I wasn’t supposed to do. It was surreal; it was self-validation that I could really, really do this. I didn’t have anybody else helping me. I negotiated my own fight, my own purse, my own this, my own that. I was proud that I was able to do that and nobody gave me anything. I didn’t have somebody come to my hometown for me to beat up for some made-up title. It was important, and I got that respect from then on. People thought, ‘Wait a minute’. It’s part of my legacy.”

‘Murdered and Missing Indigenous Women’ movement.

After surrendering her WBC 160lbs title in a unification with Hammer, the wait for redemption would be longer than many hoped. In fact, it would be 1,462 days before Reis would beat Kandi Wyatt for her second world title, the WBA super-lightweight belt. The aim for this year is to defend it – preferably on Native land. And to continue learning on the job, albeit with the support of a Philly-based team who ensure that she is their priority.

Stepping out of the ring and away from boxing, the newly engaged champion has continued banging the drum for Native American culture, engaging in language preservation and focusing on her work with ‘MMIW’. It dominated the remainder of Reis’s conversation with Boxing Social, as she spoke about Sovereign Law and innocent Native women slipping through the cracks of a damaged, dissipating independent legal system.

“It’s been an epidemic that’s plagued Native women since the colonisers first stepped foot on our island,” she explained. “They viewed Native women as being vulnerable and non-educated, or promiscuous. That’s always been their view and that’s so wrong. It’s the opposite end of the spectrum; women are chiefs, they are matriarchs, they’re leaders and warriors. These perpetrators find it easy – because it is – to come onto Native land and commit these crimes without getting charged for it. That’s because of a lack of resources, a lack of protection, a lack of a lot of things.

“It’s getting to the point where the statistics are shocking – and they’re not even close to being accurate. That’s what’s scary; the victims are getting younger and younger. They are not just targeting young girls; they are targeting young boys and women. They are coming onto Native land and stealing women away. In these isolated communities, a lot of these women just wanna get out. They see the first opportunity to get out of the res’, they might trust somebody they shouldn’t and get caught up in really bad situations, like sex trafficking and things like that.

“Native American women have been targeted for a very, very long time. This isn’t something that’s just started happening the last 10 or 20 years. It’s been happening since the dawn of our time. Native people, we know our issues and we know what happens, especially with old ways of thinking and the taboo subjects.

“I just try to use my knowledge to educate people; I go to these communities and talk to these girls, so they know they’re worthy of more and they can fight back. I can teach them how to protect themselves, and to avoid putting themselves in positions to meet people who are untrustworthy, just so they don’t become vulnerable themselves.

“I just posted about this Blackfeet [reservation] woman, 20-years old, her name is Ashley, and she went missing in June 2017. It took two months before they even started looking for this girl. That’s ridiculous. That happens a lot, since 2016 there’s been 5,000 cases unsolved. It’s got to the stage where a lot of family members stop reporting their missing loved ones as Native American because of the lack of resources in looking for them. If they report them as white, the police will look for them; but if they report them as Native, they’ll get put in a file.”

The tree remains spread across Kali Reis’s skin and, if it does represent experience and growth, one could query if there’s enough space to capture everything. The sharp, tough exterior of the champion prize fighter; the Providence girl, fighting for everything or nothing at all after overcoming trauma; the creative child, struggling to understand the complexities of divorce and broken family. Reis found boxing as she floated in the middle ground between two minorities, and it has ironically cemented her sense of fluid identity. She knows who she is, and where she’s come from; her fight continues long after she takes the decision to hang up her gloves.

Comfortable in the uncomfortable, but thriving.