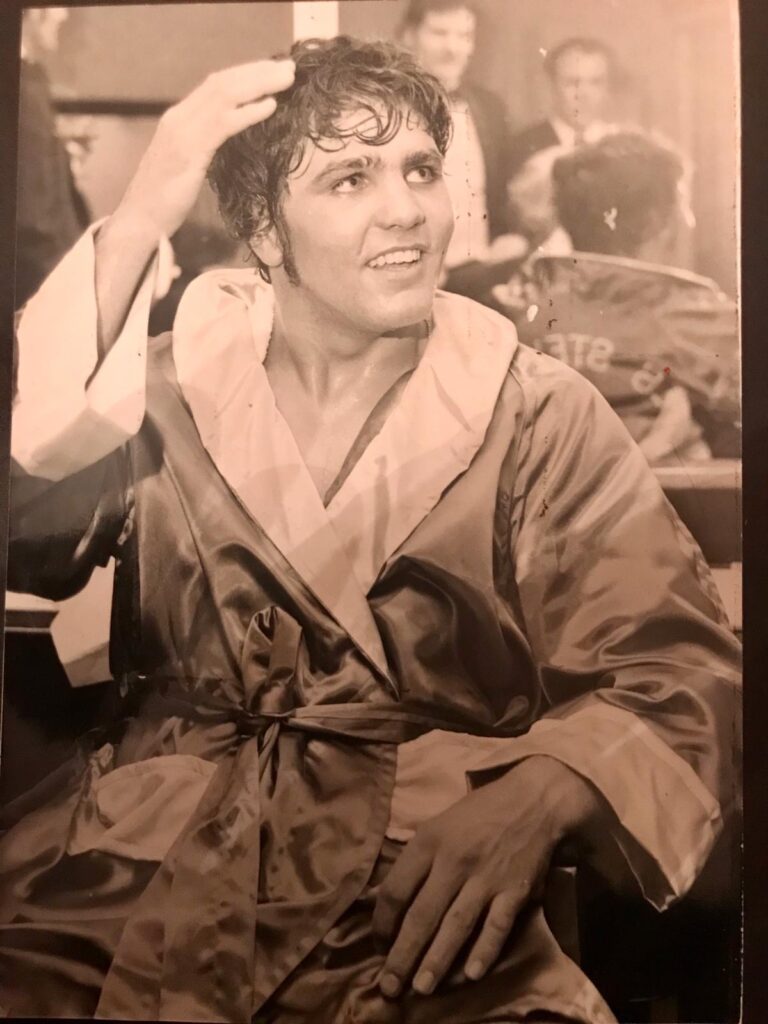

In his first column for Boxing Social, IBHOF inductee and former Boxing Monthly/Boxing News Editor Graham Houston pays tribute to the much-admired Les Stevens and remembers his creditable fighting career, which included bouts with Jimmy Young and John Conteh.

It was unfortunate for Les Stevens, who passed away on April 25 at the age of 69, that he boxed at a time when there was no cruiserweight division. Stevens started boxing professionally at 192 pounds in 1971 and his heaviest recorded weight was one pound inside what would today be the 200-pound cruiserweight limit.

I have fond memories of Stevens, who was part of the traveller community in Reading, Berkshire, and a big pal of Gypsy Johnny Frankham, an amateur teammate who was British light-heavy champion as a professional.

I was on site when Stevens won a heavyweight bronze medal at the 1970 Commonwealth Games in Edinburgh and again when he won a bronze at the 1971 European championships in Madrid.

A tribute on the England Boxing website reminded me that Stevens was a bronze medallist in the 1970 European under-21 championships.

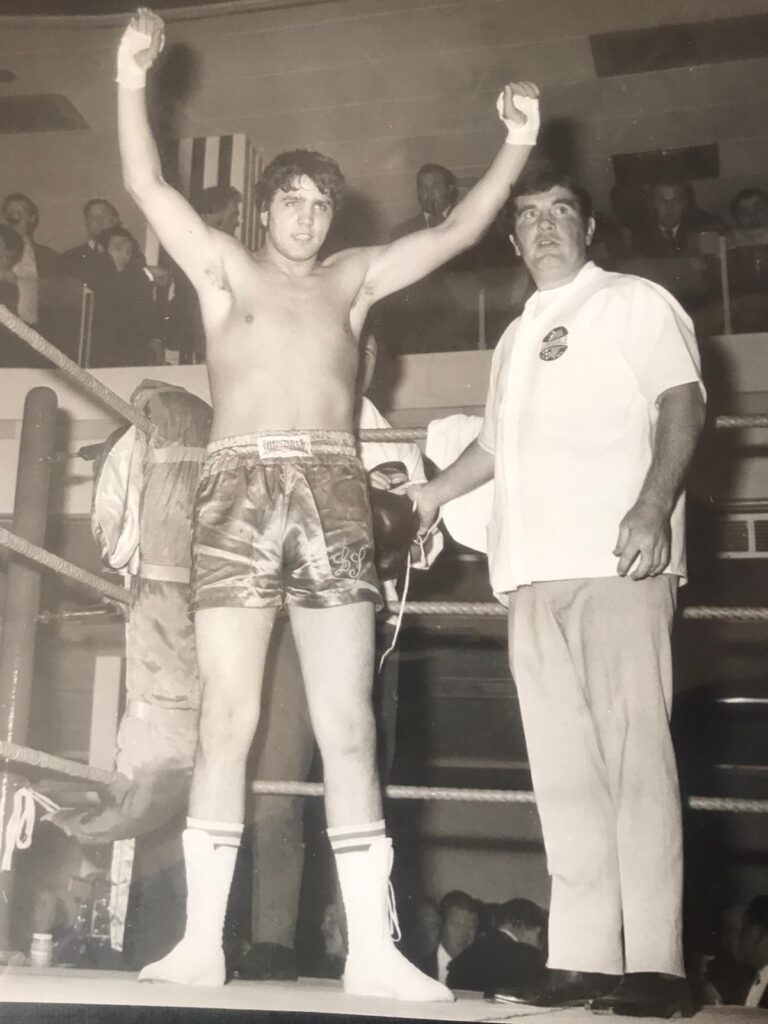

This was at a time before headguards were introduced in amateur boxing. (And now, of course, we are back to no-headguard amateur boxing.) Stevens won the ABA title (open to boxers from England, Scotland and Wales), which made him in effect British amateur heavyweight champion, in 1971. His victory over an old rival, Big John McKinty, of the Irish Guards, came after what was described as one of the most exciting ABA finals in years, with McKinty’s heavier punching being cancelled out by Stevens’ workrate.

Stevens was selected for the Commonwealth Games because first choice Alan Burton, south London’s 1969 ABA champion (and who had outpointed Stevens in the London championships final that year) was suffering from a nose injury. And Stevens didn’t let the selectors down.

In his opening bout in Edinburgh (he received a bye to the quarter-finals) Stevens outpointed the home country’s Jim Gilmour, who had won the ABA title in 1970. I wrote at the time that Stevens “fought with teeth-gritting courage”. He beat Gilmour to the punch with jabs and outworked and outfought the Scottish boxer to win a unanimous decision.

Unfortunately for Stevens, he was cut over the right eye in the last round of the Gilmour fight. And, sure enough, the cut reopened in the first round of Stevens’ semi-final bout against the 6ft 5ins McKinty, who was representing Northern Ireland.

Although bloodied, Stevens, always a smallish heavyweight, kept pressing forward. That was a really tough bout. I recall Stevens jolting back McKinty’s head with jabs, but the bigger McKinty landed some solid right hands. Stevens’ jabs had McKinty bleeding from the nose but the bigger man came on in the last round, when Stevens tired. McKinty got it on a 4-1 split decision but I thought Stevens was unlucky.

Stevens was in tremendous form in his opening bout in the European championships in Madrid the following year, simply overwhelming French champion Alain Victor. He dropped his bigger opponent in the second round and by the third the French boxer had blood pouring from his nose and was getting beaten up when his corner threw in the towel.

Three days later Stevens won a unanimous decision over Turkey’s Gulali Ozbey, who towered over him. I remember the Spanish crowd giving Stevens an ovation — and they hadn’t been particularly kind to British boxers up to then.

However, Russia’s Vladimir Chernyshev, a bear-like figure against the smaller Stevens, was too big and too strong. Their semi-final bout was all over in 95 seconds. I remember Stevens landing a right hand that just seemed to bounce off the Russian boxer. Inevitably, a big right hand dropped Stevens to his knees. He got up but looked dazed and was counted out on his feet.

“I couldn’t hurt him,” a rueful Stevens told me afterwards. “Ever tried fighting a tank?”

As a professional, Stevens won his first 13 bouts, which included a points win over Bill Drover, the rugged Canadian heavyweight who, two years earlier, had fought Joe Bugner to a draw. Stevens piled up points with the jab against a veteran who outweighed him by 14 pounds but Drover’s weight and strength told in the later stages of the eight-round bout. Even though clearly weary, Stevens punched it out with Drover in the final round, to the delight of the crowd.

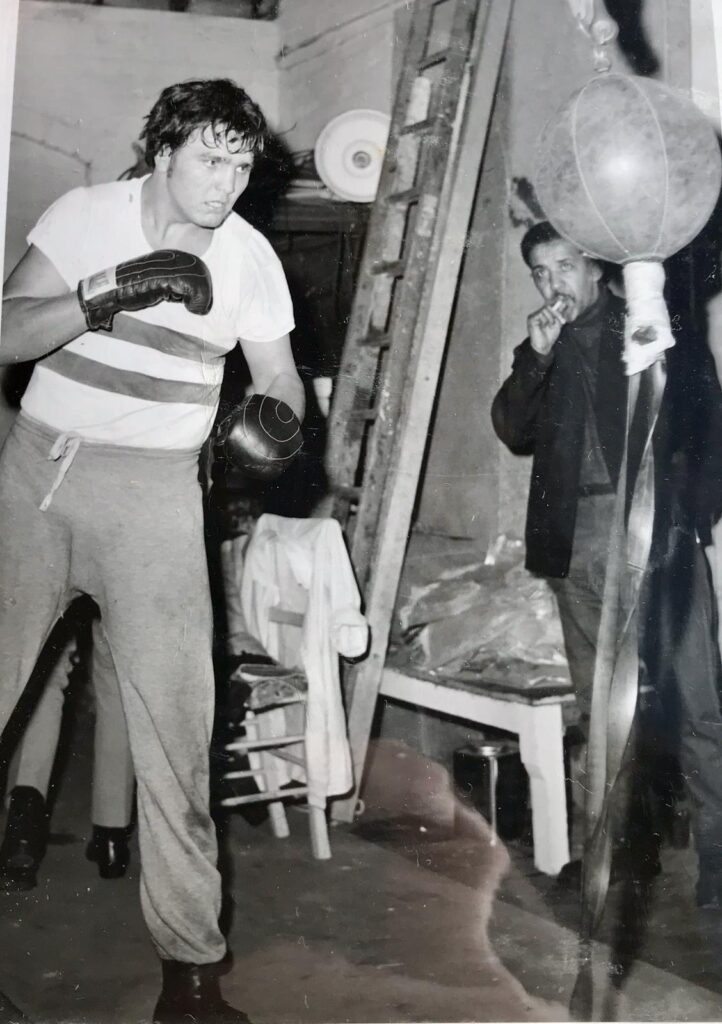

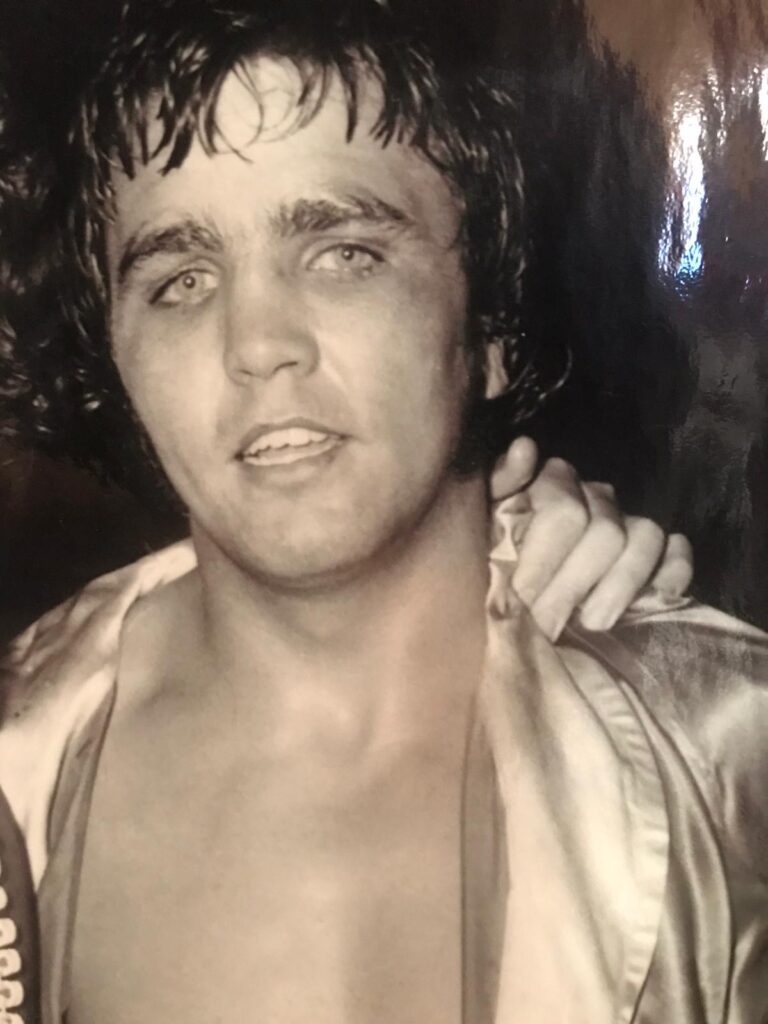

That was Les Stevens. He could box, move and jab but he was always willing to get stuck into an opponent and fight through fatigue to fire back. He didn’t have one of those ripped physiques, but he was thick-framed and sturdy. While he wasn’t a particularly heavy hitter (nine opponents halted in a record of 23-5) Stevens’ workrate could get results.

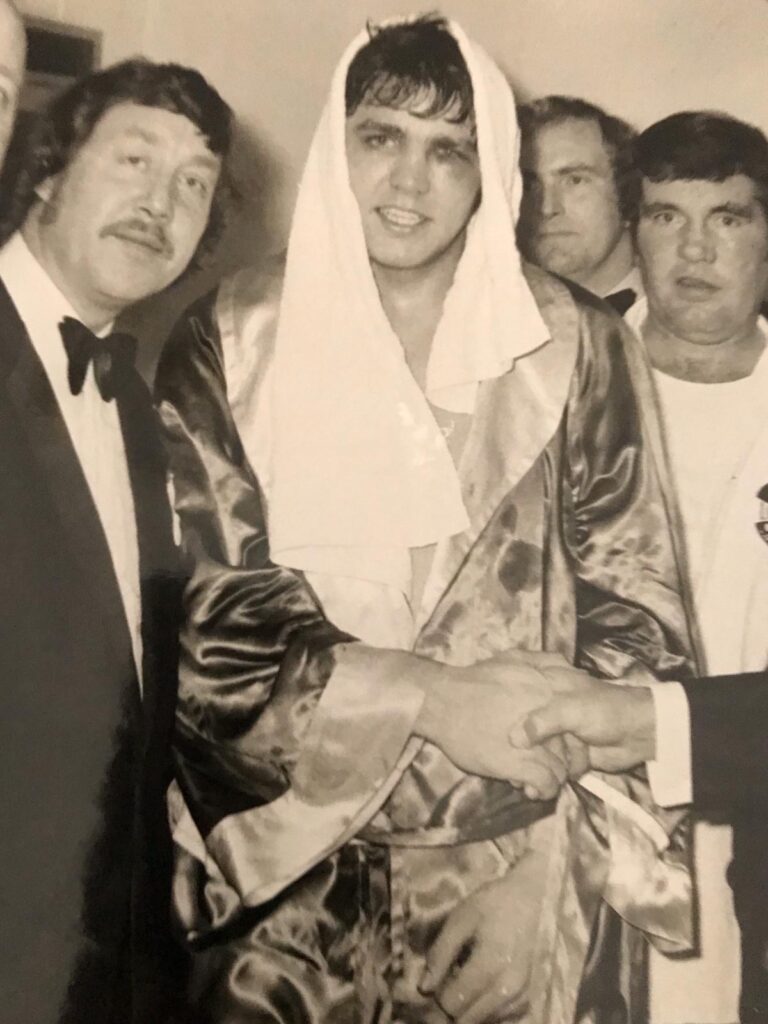

One of Stevens’s stoppage successes came when he showed a ruthless streak in a fourth-round win over American journeyman Mike Boswell at the World Sporting Club at London’s Grosvenor House hotel. As I remember it, Boswell thought he had been hit low and turned to the referee to complain — and Stevens carried right on punching. The bout was stopped with Boswell covering up on the ropes. This was considered a noteworthy performance at the time as Boswell had fought a number of contenders and been been the 10-round distance with Joe Bugner and Nebraska slugger Ron Stander.

In the 1970s there wasn’t the obsession with boxers’ records that there is today. Fighters were matched tough and won-loss-draw records could be misleading. Stevens defeated capable opponents such as Jamaican-born Lloyd Walford, dangerous Antiguan-born Rocky Campbell (who held a one-round knockout win over future British champion Richard Dunn) and Leicester’s London-born Tim Wood, who later moved down in weight to become British light-heavyweight champion.

Stevens could take a punch. His only stoppage defeat was against Conny Velensek, Germany’s former European light-heavyweight champion, when Stevens suffered a cut. I believe the only time Stevens was knocked down came in his bout with Philadelphia sharpshooter Jimmy Young at the World Sporting Club in April 1974.

Young, later to earn a high world ranking, dropped Stevens in the ninth round. I was ringside that night and thought it was more a matter of Stevens being worn down and weary than having been dropped by one big shot. He picked himself up and gritted it out to hear the bell for the 10th and final round.

We realised just how good Young was when he went on to beat George Foreman, battle Ken Norton down to the wire and give Muhammad Ali a difficult bout.

John Conteh, later to win the WBC light-heavyweight title, and Bunny Johnson, a British champion at both heavyweight and light-heavyweight, outpointed Stevens in 10-round bouts. Stevens had his moments in both contests. He was clearly beaten each time, but neither Conteh nor Johnson had it all their own way.

Stevens had his last bout in February 1979. He was only 27 but, according to a contemporary report, didn’t look his old self as he was outpointed by Tommy Kiely, an awkward and underrated southpaw from Brighton.

In retirement, Stevens was an able and much-loved trainer of amateur boxers. “He had so much respect from everyone and I never heard him say a bad word against anyone,” England performance coach Mick Driscoll told the England Boxing website. “Les has been a massive figure in both the boxing and travelling community and he will be sadly missed by all who knew him.”

I can still see Stevens, in my mind’s eye, taking the fight to bigger opponents in the amateurs, giving everything he had. If only there had been a 200-pound weight class when Stevens was boxing he could surely have been British champion. But then, life is full of “if onlys”. Stevens made the most of what he had and did himself proud. He did boxing proud, too.

Pictures by kind courtesy of the Stevens family.