When the first copy of his stunning new book ‘Leifer Boxing: 60 Years of Fights and Fighters’ arrived at Neil Leifer’s apartment it was an emotional moment for the legendary photographer.

“This is my third single subject book with Taschen,” the 77-year-old tells Boxing Social. “My first was on baseball and the second was football. They were both beautiful but this boxing book is absolutely the best I’ve ever had published.

“Eight or ten days ago when I received the first copy of the book I was shaking when I opened it. I’m not normally like that. I almost started crying – and I already knew what the book looked like!”

A former staffer at Sports Illustrated and then Time magazine in the days when those magazines really mattered, Leifer has photographed everyone “from The Pope to Charles Manson” but boxing has always – and will always – occupy a unique and special place in his heart.

“The reality of it is that no matter how much I like to talk about the other work I’ve done, I truly love boxing,” he says. “This is going to be my legacy book. I’m very proud of it and I hope that people like it.

“I’ve been involved in every single step of it in terms of working with the art director and on the design. Benedikt Taschen personally edited this book. I think he produces the most beautiful books in the world but he doesn’t personally edit every Taschen book, he can’t, but this book he did edit and he’s a huge boxing fan. He was hands-on from day one and it’s a better book because of that. I still get chills when I look at it.”

Animated and enthusiastic throughout our near hour-long conversation, Leifer’s words tumble out in that wonderful fast-talking style redolent of a dyed in the wool New Yorker.

He is also utterly without pretension; while his account of his remarkable career is regularly and refreshingly punctuated by friendly chuckles and endearing doses of modesty.

“Listen I’ve been very lucky and had a career I never could have dreamed of!” he points out. “Growing up, the idea of one day being at dinner with the president of the Philippines and his wife in the palace at Manila or at a dinner with the Saudi royal family was unthinkable!

“I never dreamed those kind of things could happen to me. The book will let people see just how lucky I was over all these years. And I’m thrilled that I’m around to see it!”

Leifer may be 77, but perhaps his most endearing quality of all is that he still exudes the wide-eyed enthusiasm and passion of the teenager from the lower east side of Manhattan who first picked up a camera at the Henry Street Settlement House back in the 1950s.

Henry Street was – and still is – an admirable institution that offers free classes to kids on the rough side of town.

As well as Leifer – arguably the greatest sports photographer of all time – it also nurtured the talents of a young Stanley Kubrick – whose contribution to cinematic history is similarly iconic.

“I grew up in a very poor neighbourhood on the lower east side,” Leifer explains. “There was a lot of crime and kids getting in trouble with drugs even back then. What these settlement houses did is they kept kids off the street. A couple of nights a week I would go to the gym and play basketball. Two nights a week we had this camera club.

“If you’re a father you’ll know the importance of a good teacher. We had a female teacher named Nelly with an unpronounceable Polish last name which I won’t try to pronounce! She taught the photography class and made photography fun.

“She really got kids keen on it. It became a hobby – quite honestly at first I didn’t realise there was a profession called a photographer but the idea that I could combine sporting events, which I loved to see, with taking pictures which I loved to do – well, the rest is history.”

A “passionate and wild sports fan” Leifer’s interest in boxing was fuelled by his father’s love for the sport and the legendary Friday Night Fights series sponsored by Gillette, which was beamed by NBC into televisions across America from 1948 until 1960.

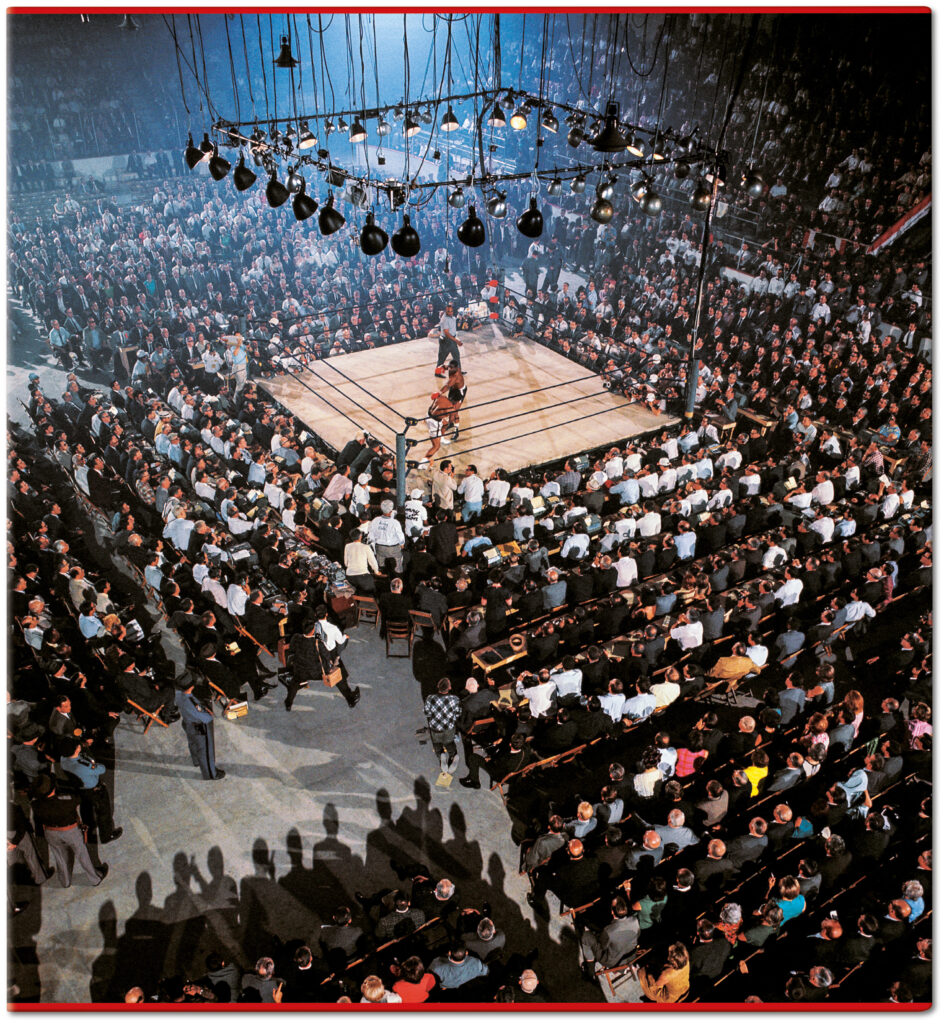

Finally, in 1959, the 16-year-old Leifer was able to attend a major live boxing match for the first time.

“Quite simply we had no money so I could forget about buying a camera or film or a ticket to a fight,” Leifer recalls. “But I was working at 16 delivering sandwiches at a delicatessen right near Rockefeller centre and I saved up my money and with my friend John Iacono [later also a Sports Illustrated snapper] and we bought five dollar tickets to the Floyd Patterson vs Ingemar Johansson fight at Yankee Stadium in June 1959. The first pictures I ever took of boxing that night are in this book.”

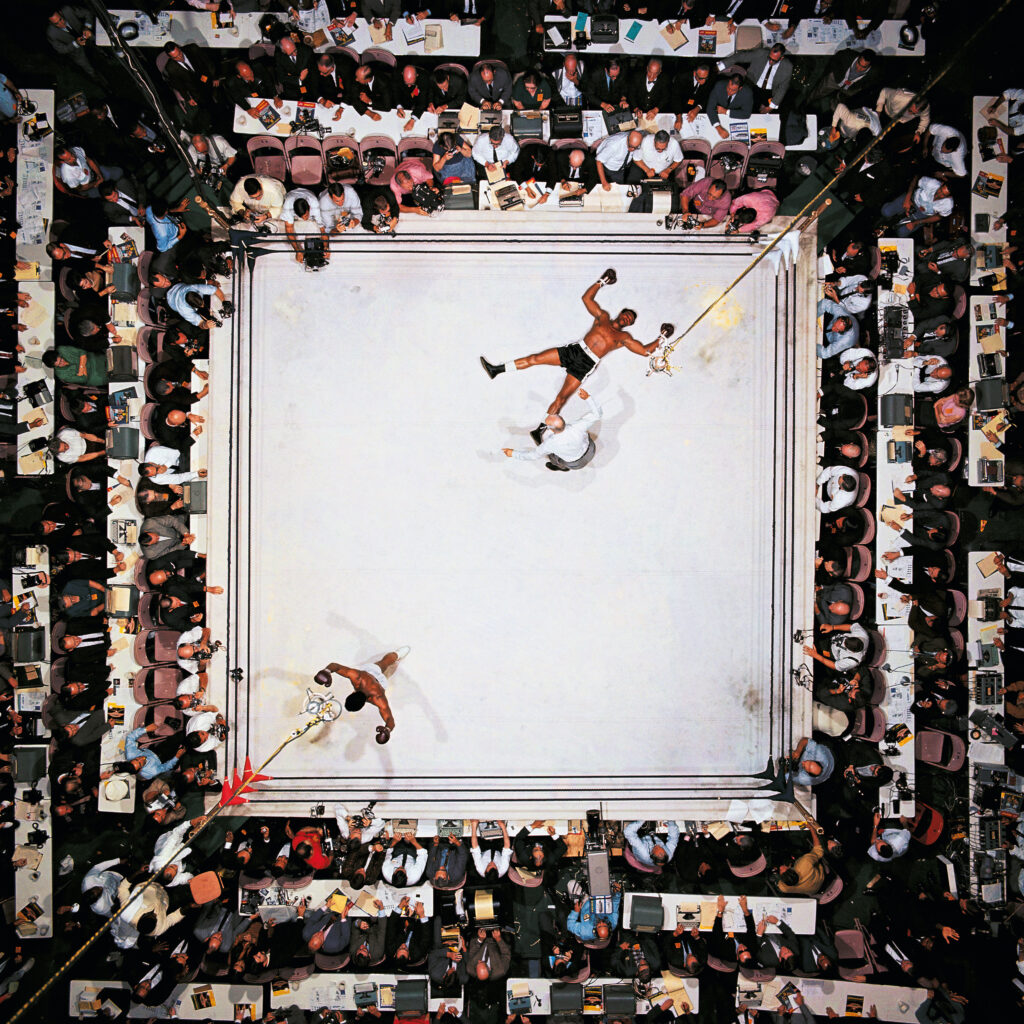

The atmospheric black-and-white shots Leifer took at Yankee stadium that fateful June night set him on a remarkable journey that would see him assemble an unmatchable and remarkably eclectic CV, as well as produce arguably the two most memorable sports photographs of all time – namely Muhammad Ali standing over a crumpled Sony Liston in 1965 and the unforgettable shot from above the ring from the Ali-Cleveland Williams fight in 1966.

embedded in the minds of most boxing fans. Copyright: Neil Leifer.

In Ali, Leifer found the perfect subject for his photographic art. He followed ‘The Greatest’ all around the world, and was there for those iconic match-ups in Madison Square Garden against Joe Frazier, in Zaire against George Foreman and Manila against Frazier again among many others.

Looking through the PDFs of his book, for me the most noticeable quality of Leifer’s classic work from those classic bouts of the ‘60s and ‘70s is the incredibly vivid colours he conjures – colours which dramatise the fights he covered and make them seem glamorous, without removing any of boxing’s inherent danger or undercurrent of seediness.

They are photos that accentuate my own love of the sport because they are taken by a man who himself loves the sport, a man who has an unerring eye for its ebbs and flows and for the personal, emotional dramas conjured by its expansive canvas.

On a technical level, Leifer explains how he achieved the unique look that characterises his work.

“The pictures that you probably remember and are referring to were taken with strobe lights, electronic flashes,” he says. “Sports Illustrated and Life magazine would spend a lot of money in those days. When Ali won the title probably 80 to 90 percent of newspapers were black and white but we were shooting in colour and spending a ton of money!

“And we wouldn’t just show up on Saturday night a couple of hours before the fight and have a beer with our buddies. We showed up on the Wednesday or Thursday at the very latest and we worked on getting enough power so we could put our strobe lights over the ring to light the ring.

“The colours you’re talking about are the result of using really good film – not the kind of grainy film that you’d shoot in natural light without artificial lights.

“To put it in layman’s terms, me shooting a boxing match with strobe lights the way we did it would be exactly the same as a fashion photographer taking shots of a model in a studio.

“When I photographed the Ali-Cleveland Williams fight we sent a big truck down to Houston full of strobe lights and there were two or three photographers. That’s a long way to send a truck – maybe 1,200 miles from New York City.

“We spent four days fixing up the lights, getting everything to work right and putting remote cameras up. It was a very expensive proposition. Nobody spends that kind of money any more.

“When I shot in Zaire and Manila I had an assistant and we sent across a ton of equipment. Who’s gonna spend that money today?

“With the quality of digital today it’s easier and cheaper, but the quality of those pictures from the 60s is better than what we’ve got today.”

is available now from Taschen , priced £800 . Copyright: Neil Leifer.

In Ali, Leifer also had the perfect subject matter with which to express his photographic genius.

“Muhammad was one of a kind,” he says fondly. “With Ali you couldn’t miss. You couldn’t miss as a writer, and you couldn’t miss as a photographer. He always gave you enough time to get what you needed. All you had to do was ask the right questions and he always had great answers.

“He’d wrap his arm around the writers and whisper that he was giving them a big exclusive and usually he’d given the same exclusive to some other writer 20 minutes earlier!

“Every time I saw him he would say: ‘You took too much time last time, how much time do you need this time, Neil?’

“I would say: ‘Well, maybe 20 minutes?’ And he’d still be there an hour later suggesting poses! He really made everyone look good who worked with him.

“The other thing about Ali that a lot of people don’t realise is that he was as good with a kid from a small-town newspaper or with a high school kid as he was with a guy from a big international magazine.

“Muhammad would give the high school kid the same amount of time he gave a Pulitzer Prize winner. He just liked people.

“When I was inducted into the International Boxing Hall of Fame, I said that I was lucky enough to follow Ali for 40 nearly 50 years – all you need to have a career like mine is find a subject like Muhammad Ali, because you couldn’t miss.

“Every writer or photographer who covered him, even the ones who didn’t like him, loved covering him because he made a hero out of them. If you couldn’t take good pictures of Ali then you weren’t very good! If you couldn’t write a good piece about Ali then you weren’t very good!”

Copyright: Neil Leifer.

During Ali’s boxing career, Leifer admits that his relationship with the boxer was strictly professional. But later in both their lives it because a deep and genuine friendship.

“When Ali was fighting I never had so much as a cup of coffee with him. I worked with him several times over the years in the studio for a Sports Illustrated cover shoot or whatever. I photographed him when he was ‘sportsman of the year’ and at his home three or four times.

“But unlike a writer who needs to talk to their subject to get some quotes for their story and has to elicit opinions and so on and so forth, as a photographer you don’t need to do that.

“Another example is Tyson Fury – I’ve photographed two of his fights and I’ve never met him. And that doesn’t matter. I’ve got a gazillion pictures of him! [see main image].

“Sure, when Ali came to the studio we’d have a chat. But he was there to pose and I was there to take pictures. After he retired, we did become close. He married Lonnie, his fourth wife, and I really got to be very friendly with them.

“In the last 25 years of his life, I saw quite a bit of them. I went to their home several times, I photographed them in Arizona, I took Muhammad and his wife to dinner in New York.”

Leifer’s knowledge of – and connection to – Ali has attracted the attention of British heavyweight superstar Anthony Joshua, whose two fights with Andy Ruiz Leifer photographed.

“It’s not a bad time to be a British fight fan, is it?” he laughs. “I’ve gotta say I really like Joshua, I had a couple of really nice conversations with him in Saudi Arabia, he sat down and had a cup of tea with us the morning after the fight. We were all in the same hotel. Joshua’s a big Muhammad Ali fan. He wanted to talk about Ali and he couldn’t have been nicer.

“So I’m a Joshua fan and, as far as a fight with Fury goes, I wanna see Joshua win. As I said, I’ve not met Fury although I do think he is one of the most charismatic and colourful fighters – probably the most – since Ali.

“Fury’s very good at self-promoting – and that’s what boxing needs, even down to the way he dresses for his press conferences. And he’s a helluva good fighter – I mean look what he did to Wilder! I never thought he’d beat Wilder that way. I had a feeling he’d win the fight but I didn’t think he’d do it like that. That was just incredible.”

Copyright: Neil Leifer.

As our conversation draws to a close, I am struck not only by Leifer’s deep love for boxing, but by his unashamed love for the boxers themselves.

It’s therefore utterly fitting that – in 2014 – he became the first and thus far only photographer to be inducted into the International Boxing Hall of Fame. (The same year, incidentally, that Boxing Social writer Graham Houston got the call from Canastota).

“It really was a thrill,” Leifer recalls. “I’ve been up there a few times since. To see all those fighters who I’ve seen fight since I was a youngster up until now is always a real thrill. And they’ve done a beautiful job up there in Canastota.”

Leifer’s voice then drops an octave as he imparts some final, telling words of wisdom.

“For me – and I know this is a broad generalisation – but I always say that of all people I’ve met in the world of sport – whether it’s basketball, baseball or football players – boxers are always the nicest.

“Where else are you gonna meet people like Muhammad Ali, Joe Frazier or Angelo Dundee? Or even Don King and Bob Arum who were just so enjoyable to be around.

“I don’t feel the same way about baseball players and basketball players as I do about boxers.”

It all comes back – in a way – to Leifer’s upbringing on the lower east side.

“Maybe it’s the fact that most boxers grew up poor and in the roughest neighbourhoods,” he speculates. “Very few of them are properly educated – many of them didn’t even finish high school but they are always the nicest guys.

“You can go right down the list – you’re never going to meet anyone nicer than Frazier, Ali, Foreman or even Mike Tyson for that matter. What wonderful and fun and charismatic subjects they are to be around! Where else apart from boxing are you going to meet characters like that?”

The question hangs in the air.

No answer is necessary as Leifer has hit upon the universal truth that makes boxing so fascinating, so compelling, and a sport that inspires such love from its devotees.

And for a moment – once again – Leifer is that same wide-eyed teenage kid from the lower east side who fell in love with boxing all those years ago.

And – for a split second – I’m there beside him, in the nose-bleed seats at Yankee Stadium, falling in love with boxing all over again through Leifer’s magical work.

Main image: Copyright: Neil Leifer.