IBHOF inductee Graham Houston recalls the incredible boxing life and times of the iconic Muhammad Ali on the 80th anniversary of ‘The Greatest’s’ birth.

This Monday would have been Muhammad Ali’s 80th birthday. It is five years since his passing yet, curiously, he still seems to be with us. It’s as if Ali’s presence has defied time and space.

So many words have been written about Ali that you don’t need a refresher course on his storied career. But I think some words of appreciation are in order.

Was Ali truly ‘The Greatest’? That is debatable. Perhaps not the greatest pound-for-pound. That would be Sugar Ray Robinson. The greatest heavyweight of all time, though? Probably yes.

One of the things that made Ali unique was that, if you think about it, he had two careers. There was the dancing, moving, jabbing, combination-punching Ali of the early years, when he was still known as Cassius Clay. That was the “Float Like A Butterfly, Sting Like A Bee” Ali.

Then, after three and a half years of inactivity due to his refusal to be drafted into the US military, we had a different version of Ali. This was the Ali who would win fights on toughness and ring generalship and sheer fighting guts rather than on speed and slick skills.

Ali changed boxing in a couple of ways. Once, fighters were always respectful of their opponents. You seldom heard a boxer flat-out disrespect an opponent before a bout. Ali changed all of that. Sonny Liston, of course, was the “Big Ugly Bear”. And so it went. Floyd Patterson was “The Rabbit”, George Chuvalo “The Washerwoman”, Joe Frazier “The Gorilla”, George Foreman “The Mummy” and so on. But Ali’s putdowns never seemed malicious (although bitter rival Frazier took them personally). Post-Ali, it seems that every fight has to be accompanied by what we now call trash talk.

And Ali introduced what we now call the staredown. Back in the day, you didn’t see fighters staring into each other’s eyes at weigh-ins and during the referee’s post-fight introductions. The change, I submit, came when Ali (then Cassius Clay) and Sonny Liston came face to face for the referee’s instructions prior to their first fight, at Miami Beach in February 1964.

Liston had taken to fixing opponents with what writer Peter Wilson called a “basilisk stare” before battle commenced. Liston’s opponents tended to avoid eye contact, as if Sonny was some sort of incarnation of the mythical creature with the lethal gaze. But not Ali. He stared right back into Liston’s eyes, unblinking, no backing down. And thus the staredown was born.

Photo: WBC.

Liston was the betting favourite at something like 7/1 on (-700). But, looking back with the benefit of hindsight, Ali would have been a great underdog bet. He was younger, faster and had been more active. Liston had basically boxed three rounds in three years: The two one-round knockouts of Floyd Patterson and a farcical one minute, 58 seconds win over a seemingly terrified Albert Westphal. In those fights, Liston had been the big man in the ring. But one thing no one seemed to realise until the two men met in the centre of the ring was that, although outweighed, Ali was actually bigger than Liston.

Ali pulled off the upset that night. And a decade later, in a fight that had echoes of the Liston fight, Ali upset the odds again when he knocked out George Foreman in the eighth round to regain the title.

Foreman was similar to Liston in that he intimidated opponents. He was undefeated, heavy handed, and the younger man. Ali was looking more hittable than had been the case 10 years earlier.

At this point, Ken Norton had fought Ali to a standstill in two tough fights, winning the initial meeting, when Ali’s jaw was broken, and losing the rematch on a debatable, split decision. Foreman, though, had crushed Norton in two rounds. Foreman had also blown away Joe Frazier in two rounds whereas Smokin’ Joe was then 1-1 in two meetings with Ali.

So, going by purely by results against opponents they had in common, Foreman was the obvious favourite. But Ali, as he had against Liston 10 years earlier, made a mockery of the odds.

The feeling many had going into Ali vs Foreman was that Ali, at 32, wouldn’t be able to keep boxing and moving for 15 rounds. But Ali, of course, fought the sort of fight that no one expected, staying with his back to the ropes and letting Foreman whale away at arms and gloves.

Before the fight, it would have been considered akin to madness for Ali to stay on the ropes against Foreman. But Ali knew differently. Foreman was physically and mentally weary by the seventh round and Ali dropped him for the full count in the eighth. And a new term entered the boxing lexicon: Rope-A- Dope.

It’s stating the obvious, but Ali transcended boxing. His biggest fights were events. In an era before pay-per-view, Ali’s fights were shown on big screens in cinemas and sports arenas. I saw a number of his fights at London cinemas such as the Odeon, Leicester Square, in the early morning hours UK time.

Ali vs Frazier I, at Madison Square Garden on March 8, 1971, was truly the Fight of the Century. Ali vs Foreman in what was then known as Zaire — the Rumble in the Jungle — was one of the most memorable fights in ring history. Ali vs Frazier III — the Thrilla in Manila — was perhaps the greatest heavyweight title fight ever, 14 gruelling rounds with Ali at one stage looking in real danger of being worn down by his bitter rival.

It now seems almost unbelievable that there was a time, in his Cassius Clay days, when critics doubted Ali’s chin and wondered if he had the heart to come back from adversity. He was knocked down by Sonny Banks and, of course, by Henry Cooper but his powers of recovery were perhaps overlooked.

Joe Frazier dropped him with one of boxing history’s most celebrated left hooks in the final round of their first fight, but Ali got right up. (He also survived a tremendous left hook in the 11th round, although that time Ali stayed on his feet.)

As for Ali’s heart, well, he proved his gameness time and again, notably when boxing with a broken jaw and yet still almost winning on the scorecards in the first of his three fights with Ken Norton.

Yet it has to be acknowledged that Ali was a polarising figure when he refused to be drafted during the Vietnam War in the 1960s. His stand cost him the prime years of his career. Arguably, he was past his best when he returned to the ring in October 1970. But he went on to have the epic fights with Foreman and Frazier and he became the first three-time heavyweight champion in history when he outpointed Leon Spinks in their rematch in New Orleans in September 1978.

I was ringside in Munich when Ali stopped Britain’s Richard Dunn in the fifth round of their May 1976 title bout. Ali outclassed Dunn not only in the ring but also at a pre-fight press conference. Dunn, a former paratrooper, tried to play on Ali’s dislike of flying by challenging him to a parachute jump. Ali, as ever quick-witted, quipped: “After 67 parachute drops you must be used to taking a dive.”

In the ring that night (actually at a little after 3 a.m. to suit US broadcasters) Ali dropped Dunn five times. But Dunn gave it a good go. “Dunn was no pushover,” Ali told the press afterwards. “He shook me twice.” As I wrote at the time: “It was fun while it lasted.”

And Ali’s career was fun. It was a great ride, from his Olympic gold medal success in Rome in 1960 to the Spinks win in New Orleans 18 years later. Unfortunately, after two years in retirement, Ali decided to come back. But it was the shell of the once great fighter who returned to the ring in 1980 to be defeated by Larry Holmes.

Ali’s physical decline as he struggled with Parkinson’s Syndrome in later years was sad indeed to behold — but he left an imprint on the boxing world like no other.

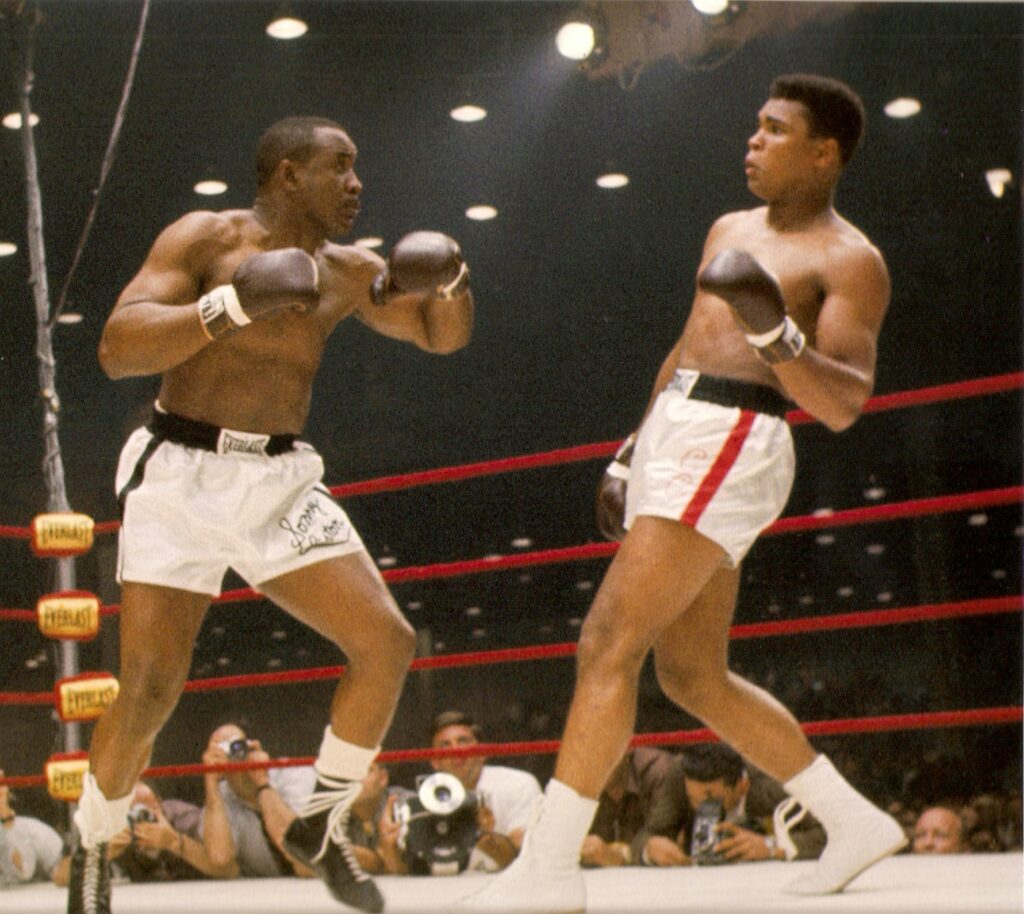

Main image: Grand rivals Ali (left) and Frazier do battle during their second meeting in New York in January 1974. Photo: WBC.