In his latest column, IBHOF inductee Graham Houston looks at the confusion surrounding the scoring of even rounds and explains why professional judges are still supposed to pick a winner in the closest of sessions.

It was just a four-rounder, but the bout in Las Vegas between Mike Sanchez and Eric Mondragon this past week brought an old, familiar question back into focus. It is the question of whether it’s appropriate for a judge to score an even round or whether a judge should be expected to always find a winner no matter how close the round.

Commissions in North America frown on judges scoring a round even. “A good judge should always be able to find a winner in a round,” Marc Ratner told me when he was head of the Nevada commission. “Even if it’s one boxer making the fight or doing a bit more.”

This brings us to the four-rounder between 130-pounders Sanchez and Mondragon. Each man scored a knockdown in the first round. A 10-10 round, surely?

Well, not necessarily.

Photo: Mikey Williams/Top Rank.

Sanchez dropped Mondragon with a left uppercut from his southpaw stance. He controlled most of the opening round. But Mondragon gradually pulled himself together and landed a right hand that knocked down Sanchez just before the round ended.

So, in the Nevada commission judging criteria, the knockdowns cancelled each other out. Therefore the round went to the boxer who won most of the round. That would be Sanchez. All three judges had Sanchez winning the first round 10-9.

you score the round? Photo: Mikey Williams/Top Rank.

The boxing commissions’ view in the US and Canada is that by asking a judge to find a winner in every round it ensures that a judge remains fully focused on every second of every round.

Another argument against scoring even rounds goes like this: if a judge can’t find a winner in a close round, and makes it even, why not do the same in every other close round?

This sort of thing happened in the past. Swiss judge Rolf Neuhold, perhaps in keeping with his country’s position on neutrality, scored every round even in a WBC 154-pound title fight between Italy’s Carmelo Bossi and local fighter Jose Hernandez in Madrid in 1971. His scorecard (on a five-point system) came to 75-75.

The French judge had the fight a draw, too, and the German judge had it one point in favour of Hernandez. But spare a thought for Judge Neuhold. He might well have thought that if every round in this fight was closely contested, as seems to have been the case, and he made the first round even, then what was wrong with making every round even?

The fight ended up as a draw. With just a one-point difference on the scorecards after 15 rounds, this was quite likely a difficult fight to judge. But surely not to the extent of failing to find a winner in any of the 15 rounds?

Jack Dempsey was a great fighter but not so much as a referee and judge. As referee and sole arbiter, the old Manassa Mauler made seven out of 10 rounds even in a heavyweight fight between local battler Rex Layne and ex-champ Ezzard Charles at Ogden, Utah, in 1953. Dempsey gave Layne two rounds and Charles one round.

Seven out of 10 rounds even was a bit much.

I used to score some rounds level myself. Back in the day that was the norm. It wasn’t unusual for a referee — in those days the sole judge — to score several rounds even in a title bout. Take the British heavyweight title fight in 1971 when Harry Gibbs scored Joe Bugner a narrow and controversial winner over Henry Cooper. Gibbs had four rounds even in that contest — the seventh, eighth, 10th and 11th. (His scorecard was published in his autobiography, entitled Box On.)

These days, such a scorecard would be viewed with disfavour by boxing commissions. Times have changed.

Judges do still score even rounds in various jurisdictions but it is now rare. In Britain and Europe one still sees a 10-10 round on a judge’s scorecard but it is usually just one round out of 12.

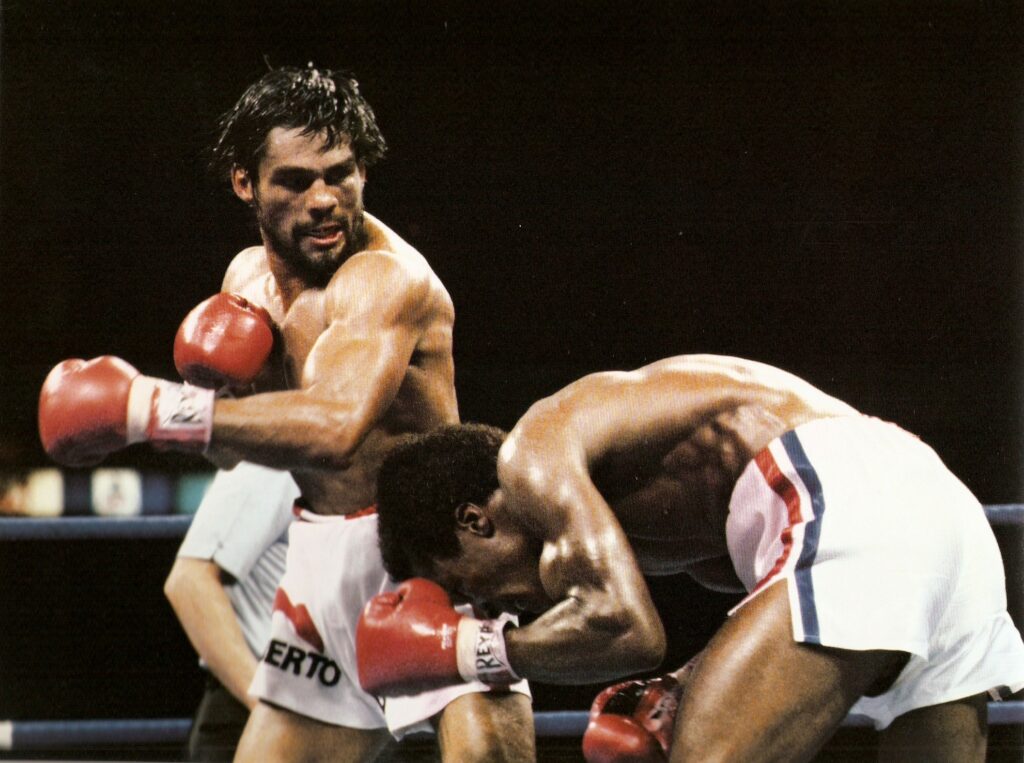

Things came to a head, if you will, after the 1980 welterweight championship fight between Roberto Duran and Sugar Ray Leonard in Montreal. Italian judge Angelo Poletti had 10 of the 15 rounds even. He gave three rounds to Duran, two to Leonard.

in the Duran-Leonard I fight. Photo: WBC.

In that same fight, French judge Raymond Baldeyrou had five rounds even, including the 15th, which was arguably Leonard’s best round of the fight. Harry Gibbs scored four rounds even.

I believe that the amount of even rounds scored by the judges in this fight prompted a change in thinking. It was an extremely high-profile bout, but the judges had 19 rounds even between them out of a total of 45 rounds.

This was considered unacceptable, especially the Angelo Poletti scorecard that showed him unable to separate the boxers in all but five rounds. Sports Illustrated described Poletti’s card as a monument to indecision.

When I was a boxing judge in Vancouver, the commissioner, Dave Brown, in his pre-show briefings, would always ask his judges to avoid scoring an even round unless we absolutely, positively couldn’t split the fighters. In other words: We don’t ban 10-10 rounds, but please don’t do it.

Today, in North America the only time you’re likely to see a judge score an even round is if a boxer has a point deducted. Thus, a 10-9 round in favour of a boxer becomes 9-9 with the point deduction factored in.

A familiar argument goes something like: “Why can’t the judges be more liberal in their scoring? Then a really close round could be 10-9; a clear round, 10-8; a dominant round, 10-7; a dominant round plus a knockdown 10-6, and so on.”

This was tried in New York State when Randy Gordon was commissioner. The result was that the scoring was all over the place. You look at the scorecards from that period in New York boxing history and you have no idea what happened in certain fights. Take the 1989 middleweight bout between Dennis Milton and Michael Olajide, which Milton won by split decision. Two judges had Milton winning, with scores of 94-91 and 94-90 respectively, while the third judge had Olajide winning, 94-92.

The judges were merely following the commission’s directive and being liberal in their scoring, but who can make sense of those scores? An aficionado would have no idea what sort of fight those scores reflected.

Now, it might seem unfair, in a 12-round bout, if one boxer gets the benefit of the doubt in seven tight, either-way rounds to win a decision even if his opponent wins five rounds clearly. But that’s just the way the system works.

One could argue that Sugar Ray Leonard cunningly made the system work for him by stealing close rounds with late flurries against Marvin Hagler. The counter argument is that Leonard employed brilliant strategy.

Arguments about scoring will likely always be with us. We’ve seen experiments with open scoring, consensus scoring and liberal scoring. The present system might not be perfect but it’s probably as good as it’s going to get.

As for scoring even rounds, a case can be made for and against. I prefer not to score rounds even for several reasons. The first is that it smacks of taking the easy way out. The second: anyone can score a round even. And, as outlined in cases such as Angelo Poletti’s scoring in the Duran vs Leonard fight, scoring rounds 10-10 can get out of control.

But the most compelling reason is that if a judge is expected to find a winner in every round it surely guarantees intense focus.

You sometimes hear ringside scorers on TV say something like: “I’ll score that round even” or “I can’t pick a winner in that round.” Fair enough. But pro judges aren’t supposed to think that way.