The Old Abbey Taphouse pub is situated on the Manchester Science Park. It is the last remaining part of the Greenheys estate and, prior to January of this year, I only knew about it for two reasons. The first is the fact that it used to serve proper, on the bone curried goat and the second is because I walk past it on a regular basis when heading to Hume.

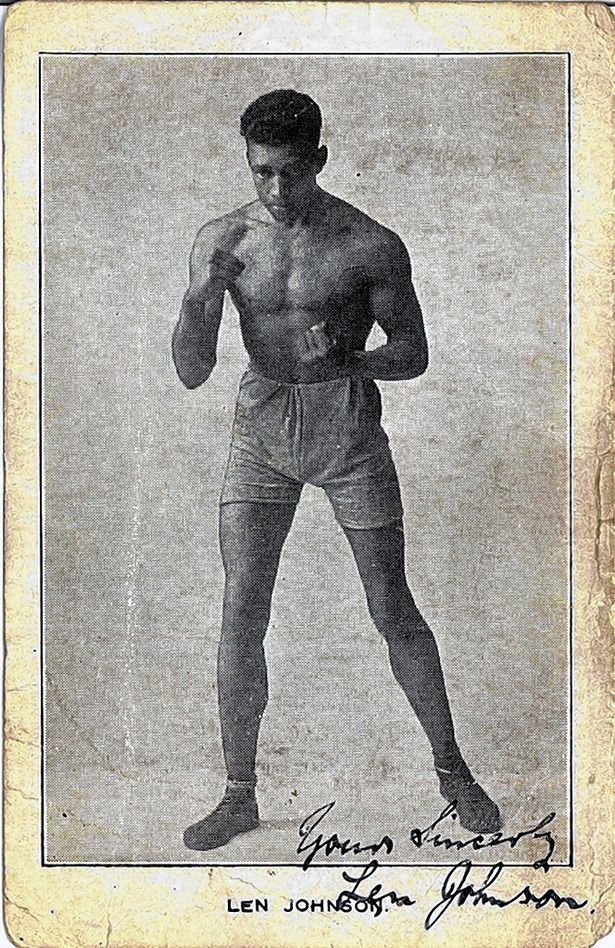

If you delve deeper into the history of the pub you will unearth a story that covers boxing, politics, race and class, a story that focuses on Len Johnson, acknowledged by many as one of the best fighters to have never won the British title.

In fact, Johnson didn’t even get to contest it. It isn’t that he wasn’t good enough, the reason why he never got a shot is at once simple and complex. You see, Len Johnson was a black man and, until 1948, there was a colour bar in boxing right here in the United Kingdom that had been put in place by Winston Churchill and was supported by the British Boxing Board of Control.

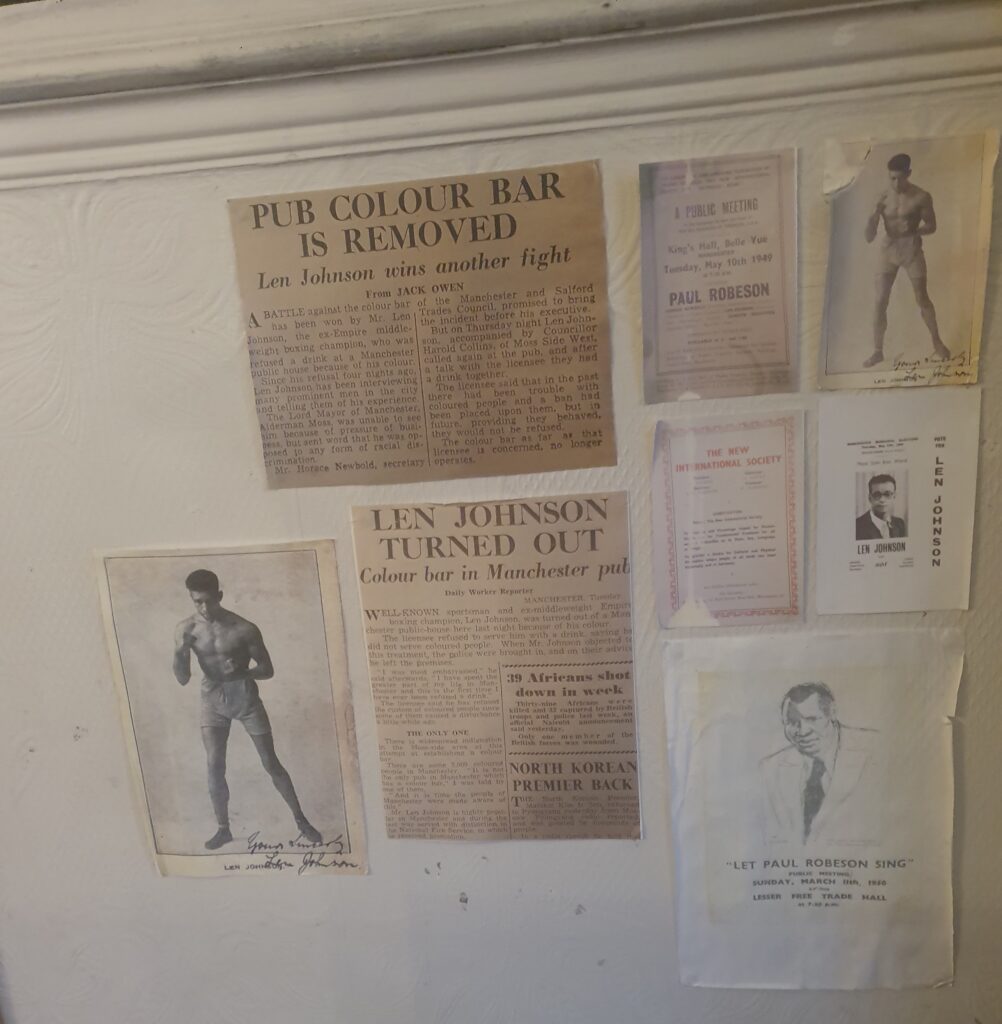

In fact, the reason that the pub in question went down in the annals of history is because Johnson and two white companions, one of whom was fellow Communist Party Member Wilf Charles, walked in there in September 1953 for a drink and the owner refused to serve Johnson due to the fact that he was black. It wasn’t an accident, either, as Johnson used the incident as a platform to bring some race reforms to the city of Manchester.

He took his fight all the way to the Town Hall, the Lord Mayor Alderman Moss supported him, and he was still a well-regarded and popular figure due to his career as a boxer. In no time at all a protest began. Within days Johnson and the pub landlord went for a stroll and then had a drink together — a soft drink, as Johnson was teetotal. It was a significant moment in the history of this city’s long-forgotten colour bar.

Photo: Terry Dooley.

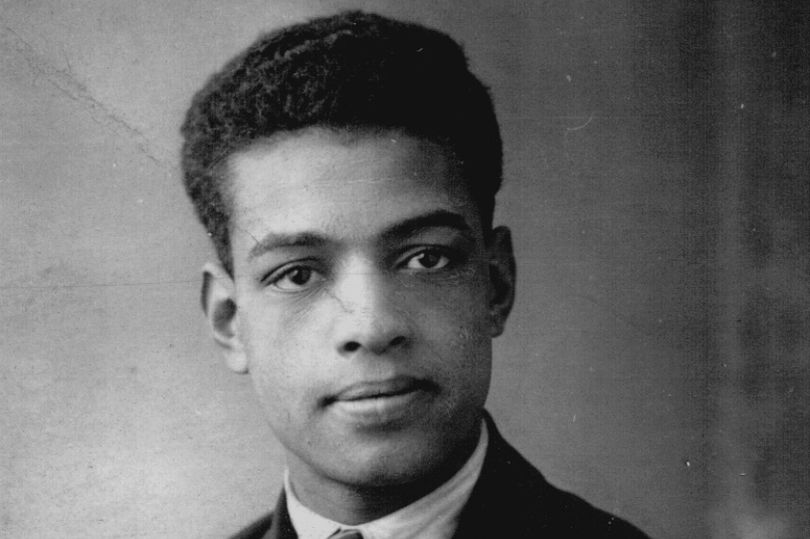

Johnson was the son of an African father, Bill, who hailed from Sierra Leone. Bill was a merchant seaman and fairground booth operator who was said to have been easy to spot due to his height. Bill Johnson came to Manchester by way of the Canary Islands and Liverpool back in 1897. His mother, Margaret Maher, was a Mancunian of Irish descent. Just before Johnson was born, his father had put a shilling on a horse, Black Sand, at odds of 100-8, so it was a doubly blessed day.

Soon after his brother, Albert, was born and Johnson’s father lost his job, so they moved to Leeds, where Billy found employment in a boxing booth ran by Gal Hague. It moved up and down the country and the two boys travelled with him. Another brother, Billy, was born in Leeds. Billy was a waiter and utility man by this point. The family lived in a house off the Pontefract Road, half of the living room was underground due to either the layout or subsidence and the family shared it with cockroaches. If they moved around in the dark, they could hear them cracking under their feet.

“We lived in a state of perpetual semi-darkness, relieved occasionally by flashes of feet and ankles as they went by the window at street level,” Johnson wrote in an autobiographical essay about his life (the essay is part of the Len Johnson collection at the Working Class Movement Library in Salford). “A haven for vermin…from those that share the bed to those that nest under the floor boards. The grisly effect was added to by the rasping noise by their [the cockroaches’] bodies.”

Before they moved to Manchester from Leeds. they had lodged in Clayton with a family called the Connells. Johnson stated that they were like parents to his mother and surrogate grandparents to him. Times were tough in Leeds so they headed back to Manchester in search of work. It was especially hard for Johnson at school, where he was constantly subjected to racist slurs. He wrote in his autobiographical essay that the insults made him think twice about joining in the bullying of other children who were targeted for ‘marked physical blemishes’ despite having a ready-made excuse for lashing out himself. This innate sense of justice may have planted the seeds of his post-boxing life as a political activist.

By the time he was 13, Johnson was already working as an errand boy for a local druggist, where he filled tins with rat poison. At first, he refused to use gloves, so his hands burned on contact with the phosphorous that was one of its chief ingredients of the concoction. Johnson had harboured an ambition to become an engineer but became a moulder on his employer’s advice. A key part of this job involved learning how to lace his boots in a way that would ensure they could be quickly cut off if molten liquid got into them.

Johnson got a job in Gorton engine works before leaving at the age of 17. Boxing became a big part of his life via the Alhambra club, which was run by ex-boxer Jack Smith. He also boxed in the Bert Hughes-owned boxing booths. This is where he honed his skills.

Despite losing his first two fights, there must have been something about Johnson as he was encouraged to carry on with his career. As in his other occupations, he learned his trade on the job. By the age of 19 most of us are just finding our feet and embarking on either work or study, Johnson was engaging in 15-round fights.

Photo: Terry Dooley.

Things really started to kick in when he rose to prominence in 1925 by twice beating current British and Commonwealth, and former EBU middleweight Champion Roland Todd in non-title fights. Johnson also beat Ted ‘Kid’ Lewis and outpointed future world champion Len Harvey before losing away to EBU welterweight title-holder Piet Hobin in Germany. Johnson had 20 fights in 1924, 14 in 1925. As a professional he beat respected names like Ted Moore and Len Harvey, who would go on to win the British title himself at middleweight, light-heavyweight and heavyweight.

Johnson pushed on despite not being able to contest the British title due to the BBBoC’s ‘Rule 24’. This rule stated that British titles could only be contested by people “Born of white parents”. However, his fight against Sunny Jim Williams in 1929 was billed as an ‘Elimination contest for the world’s middleweight title’ and the programme stated that: ‘Both men have a challenge filed and deposit registered with the New York Commission for a match with Mickey Walker,’ (Quote taken from a Boxing News article by Ron Olver in the August 29, 1985 edition).

Johnson won that one, but never got to fight Walker. Another opportunity had passed him by, and he was put back on the boxing treadmill. The British title would not be contested by a black man until 1948 when Dick Turpin defeated Vince Hawkins over 15 rounds at Villa Park for the middleweight belt. By then, it was far too late for Johnson.

A May 1932 contest against Harvey was dubbed the “Unofficial British middleweight title” fight yet he was told that even if he should win, the victory would not be recognised. It was a moot point, though, as he lost on points over 15 rounds. For years, Johnson boxed on in the knowledge that he would never be British champion. Johnson later claimed that Lord Lonsdale learned of his plight and said: “I am very sorry for his sake, because he is a very nice fellow and a really nice man with a fine personality and a splendid boxer. But there it is.”

The colonies were kinder to him, though, as a win against Harry Collins for the then-Empire, now Commonwealth, middleweight belt in Australia in 1926 won over the locals and netted him £555 [figure taken from his Topical Times column on January 21, 1933]. Johnson took time out for a holiday over there, shark fishing with the local people and generally having a good time. Rejected by his country, Johnson sometimes had to lead a nomadic existence in his chosen profession. His writing about his time in Australia seems freer than his other writing. Acceptance perhaps allowed him to be more meditative or maybe it was just due to the distance he had put between himself and England.

America also came calling for the skilled boxer during his career, yet the American experiences were referred to as disasters in his Topical Times February 4, 1933 column. Securing proper sparring was not an option at sea so he sparred with the ship’s sailors en route to stay sharp. Johnson had a wife, former bookbinder Annie Forshaw, who like his mother was also of Irish descent and their baby died while they were there. Back then you could not just jump on a plane and be home within days, so the baby had already been buried by the time they managed to get back to Manchester.

Following this tragic setback, Johnson went back to America to see if Ted Lewis could get him properly situated. He stayed at Grupp’s Gym in New York. Lewis, Mike McTigue and others were also based there so they all had good sparring. A fight with Phil Kaplan fell through when Kaplan turned it down.

One against Eddie Whalen also fell by the wayside because they said he was too big. ‘All Whalen had to do if he thought I was too big was to claim forfeit when on the scale and then refuse to fight,’ Johnson wrote. Whalen fought Canada Lee instead, so Johnson recalled that he: ‘[G]ot together my trunks and went home’. His US connection Jimmy Johnstone sent Johnson the fare for a third visit, but, again, nothing came of it; he later described himself as: ‘The world’s champion waiter.’

By October 1933, it was all over for Johnson. A loss to Jim Winters prompted him to retire. For too long he had hoped against hope that it would happen for him only to say: “The prejudice against colour has prevented me from getting a championship fight. I feel now that there is no use whatever going on with the business.” [Michael Herbert,Never Counted Out 1992].

Upon retiring, Johnson wrote: ‘Altogether I have done not so badly considering that my first fights found me to be useless,’ while adding that he had liked to, “Poke his way to a win”, if he could behind his left. Despite the setbacks and frustrations, he told Bert Daly that if he had his time over again, he: “Wouldn’t have changed a thing” [Boxing News]. Indeed, Johnson still held a candle for boxing, and you can sense this when reading the articles and stories about it that he wrote for the Daily Worker newspaper and other publications.

When he died aged 71, Daly lamented the loss of a brilliant man and fighter, telling Ron Olver of Boxing News that: “He was well-respected both as a fighter and as a man, but found himself battling against an opponent he could never lick — the colour bar. Noted for his defensive skills, he had a gem of a left hand and could block punches in a style rarely seen today.”

He also had harboured hopes of taking his writing further. Sadly, submissions to the Television Writing School Limited in the mid-1960s were rejected due to the company folding. Johnson epitomised the phrase, “If it wasn’t for bad luck, I’d have no luck at all”, yet he continued to fight in other areas throughout his life.

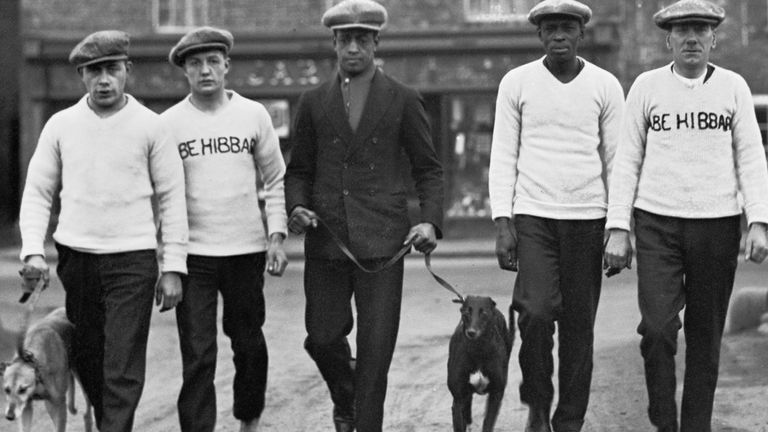

Photo: Manchester Libraries.

Like many fighters, Johnson had to take on various roles after retiring. He had invested in a boxing booth in 1926 and maintained it for as long as he could. Future world flyweight Champion Benny Lynch was one of the fighters who boxed for him. When talking about Lynch, Johnson told Elky Clark of the Daily Record that: “[I] have seen the qualities that will surely make him a world champion. I cannot take him any further.”

Most people in the trade would have recognised the talent of Lynch, got in his ear, and become either his manager or trainer. Johnson had much more humility than most people. A job as a bus driver came his way after he left the civil defence following World War 2 only for tragedy to strike when a child stepped out into the road and was hit and killed by the bus he was driving. The former fighter also worked as a bookie and a trucker. He had driven fire engines in Moss Side from 1939 as part of his role in the TGWU (Transport and General Workers’ Union).

Johnson was denied the chance to establish a legacy in the boxing ring, but he left his mark in the political arena, a place he spent the rest of life until his death in September 1974. During one of his self-declared “Fed up” periods in boxing, Johnson met American musician and activist Paul Robeson and the two struck up a friendship. By 1945, Johnson was a card-carrying member of the Communist Party; he had been recruited by Wilf Charles, who remained his friend throughout Johnson’s life.

The Fifth Pan-African Conference was held that same year in Medlock Town Hall. Johnson played a key role in putting it all together and that conference was credited as a key part of the start of the liberation of sections of Africa. It was also key in drawing attention to race relations. Robeson and Johnson had worked together on international campaigns in the 1940s and continued to do so in the 1950s. Johnson even led the British side of the ‘Let Paul Robeson Sing Again’ campaign.

Johnson’s stand against the local colour bar wasn’t the end of his political campaigning, though. The former fighter stood as a Communist Part for Moss Side East in 1949, 1955 and 1961 — he was not successful. Still, he remained a big voice in trade union movement and implored young people to join the Young Communist League. In addition to this, he also taught them how to box for free.

His political life culminated in the creation of the New International Society, which he formed in 1946 alongside Wilf Charles and International Brigade veteran Syd Booth to combat growth of local far-right groups. Johnson said: “The society’s aims are simple: true internationalism, colonial liberation, peace and the ending of race discrimination.”

In total, Johnson entered the ring 135 times according to his official record (95-33-7, 36 KOs) — many, many more times off the record when in the booths — and there were times he made that loneliest of walks not knowing if he would be able to see the punches coming.

When I was pouring over his clippings earlier this year the thing that stood out was his sensitivity and compassion for others, as evidenced by his decision to adopt the three children of his second wife’s sister after her death. He also cared for his wife Maria’s three children so had many mouths to feed during tough times.

One of the surviving adopted children, Brenda (who was one of Maria’s sister’s daughters), summed Johnson up when talking about him with Michael Herbert 40-years later for Never Back Down!: The Story of Len Johnson, Manchester’s Black Boxing Hero and Communist. She said: “When I think back, it took a black man to take three children that our own father didn’t want to know and he was a white man…He could have turned ‘round and said ‘No, let the welfare have them.’ But he didn’t. That meant he had three more mouths to feed. He was one hell of a guy. I can’t put my feelings into words.”

There is not a single plaque or a monument to Johnson here in Manchester. All we have to mark his place in history is a wall of press clippings in the Old Abbey. You can help change that by signing the petition to have something put in place to remember a fighter who was forgotten for far too long but who is now starting to be remembered and celebrated again.

The BBBofC should also consider awarding him and others posthumous British title belts to finally give these long-forgotten fighters the recognition that their careers deserved.

To sign the Len Johnson monument petition link, click here> http://chng.it/pW95sRf7jd

Main image: Wikimedia Commons.