Somewhere between the striking poverty of Kibawe, Philippines and the posturing of modern day Hollywood, a group of young teens sat bleary-eyed awaiting the opening bell of a bout between two very different fighting men.

The contest started at around 5am, the boys had soaked up plenty of alcohol and of the six in attendance only one had picked the smaller, seemingly unassuming man to triumph.

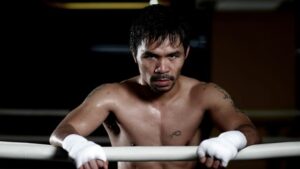

The first of the fighters had a face with jagged edges, telling its own story of hardship with each bead of sweat frantically trying to escape whilst they still had the chance. The other man was eerily happy to be there – happy to perform destructively for his audience. He was smiling before the fight, walking calmly to the ring to face a tough Mexican and, as he brutally battered David Diaz just over a decade ago, Manny Pacquiao’s (61-7-2, 39KOs) fanbase had grown by five, at least.

It would be unfair to label Pacquiao purely as a ‘fighter’, with a CV as long as his arm, filled with many colourful entries. He’d often finish his fights in Las Vegas before darting across to another venue, performing as a singer. Or there was his brief spell playing basketball professionally. But now, he seems to have found his true calling – his purpose outside of our bloodsport – with the BWAA’s Fighter of the Decade currently juggling boxing with his demanding role as a Senator, looking and sounding impeccably, aged forty.

As he approaches his fight with long-reigning WBA welterweight champion, Keith Thurman, it was a privilege to talk legacy and longevity with one of the finest fighters of our generation, exclusively for Boxing Social.

From fighting men on the streets of Manila at fourteen-years old to travelling across the world in search of success, his story had already been shared. The family man who now commands legendary status within and around boxing had dragged himself up from the gutter, scrapping for money to help heal a broken home after his parents had separated.

He’d achieved that – selling over one billion dollars worth of pay-per-views and taking home purses far surpassing his wildest dreams. So why now, as he firmly approaches middle age, was Manny Pacquiao still fighting?

“I want to show everyone that forty is just a number”, he told me. “If you stay active and take care of yourself, you can accomplish a lot. Forty is just the beginning of my life. A lot of media [outlets] say I am too old to be fighting and that I will lose to Keith Thurman. I am using that as motivation. It inspires me.”

Driven by his recent detractors, the ‘Pacman’ of old may prove difficult to resurrect. However, with his advancing years he’s become smarter with his meticulous preparation. A short spell spent separated from long-time trainer, Freddie Roach allowed the eight-weight world champion some space, working on his own time, with Buboy Fernandez. After rekindling their unique relationship, Pacquiao and Roach are keen to showcase what’s left, recently signing a promotional deal with Al Haymon in the Autumn of last year.

That infamous pairing had entered its eighteenth year, sparked initially during a chance meeting in the Wild Card gym that would later become the Filipino’s second home. Seeing them reunited gave the impression that normal service could be resumed. His latest victory was in January, a comfortable unanimous decision over loud mouth irritant, Adrien Broner, proving there was life in the old dog, yet. Roach, who had called for his charge’s retirement at various points in the past, seemed rejuvenated, as did his loyal fighter.

Manny explained, “When I first came to the United States, it was for vacation. That was in 2001 [and] I went to San Francisco and then took a Greyhound bus to Los Angeles. I wanted to get a little work in when I was in Los Angeles and someone recommended Wild Card Boxing Club in Hollywood. I had no fights planned. I went there and asked if I could do mitts with someone and the man behind the counter said he would do it. His name was Freddie Roach.”

As fate would have it, the man sitting behind the counter was the very same man that would guide him through boxing’s murky waters, beating superstars such as Oscar De La Hoya, Juan Manuel Marquez, Erik Morales, Marco Antonio Barrera, Miguel Cotto and Shane Mosely.

For Pacquiao, the connection was instant. He knew he’d found the perfect coach, or more importantly the ideal mentor, barely an hour after stepping off the Greyhound. Roach has been like a father to him, helping him adjust to life in the States and superstardom both at home in the Philippines and globally. The fight with Keith Thurman will be their thirty-seventh together, yet the future Hall of Fame fighter recalled their first session as though it was yesterday.

“After the first round [on the mitts with Freddie], I went back to my corner and said, ‘I just found my new trainer’. That was in 2001. A few months later, we were fighting the IBF 122lbs champion, [Lehlo] Ledwaba and that is how my US boxing career began. It was destiny. I am so grateful for being directed to Wild Card.”

His Florida-born opponent, nicknamed ‘One Time’ was one of boxing’s more bizarre characters. Extremely intelligent and openly spiritual, he’d suffered with injuries in recent years before returning to fight Josesito Lopez. The Mexican challenger poured on the pressure and had Clearwater’s Thurman wobbled around the midway mark, though the champion prevailed, showing plenty of heart and winning narrowly on points.

Pacquiao was taking nothing for granted, though, and spoke highly of the man he’ll face this coming Saturday. When Manny was making his professional debut, Keith Thurman was only six years old. He’s unbeaten, enjoying his prime and desperate to improve upon his last outing against Lopez, before hunting mega fights with fellow welterweight world champions Errol Spence, Shawn Porter or Terence Crawford. But could the elder statesman upset that apple cart with one last hurrah?

“How do I beat Keith Thurman?”, he asked rhetorically, “By training my hardest and being at my best. It is all about being at my best because you cannot predict what your opponent will do. I rate Keith Thurman as one of boxing’s top fighters. No one has beaten him. [I maintain my career through] discipine. The busier I am, the more I am able to accomplish. I am good with my time management.”

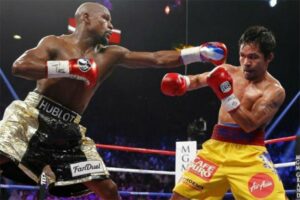

Like many others, I’d pondered what comes next for Manny Pacquiao, win, lose or draw on Saturday night in the MGM Grand, Las Vegas. One man that had comfortably beaten the Senator was the divisive, brash Floyd ‘Money’ Mayweather Jr. Everything that Pacquiao was, Mayweather wasn’t. The flash, diamond encrusted jewellery, the rucksacks bursting at the stitching with dollar bills – he flaunted his gaudy achievements at every opportunity.

That contest, dubbed the ‘Fight of the Century’, had apparently come too late as both parties eased towards their late thirties, failing to deliver as they might have five years prior. Pacquiao never got started, citing a shoulder injury after the scorecards had dealt him a further crushing defeat. On the most grandiose of stages, generating a record-shattering purse, the pride of the Filipino people had fallen short.

Rumours of a rematch have been circling ever since, but Manny was quick to pour cold water over the suggestion, “Floyd is retired. If he can no longer fight at this elite level that I am fighting at, it would make sense for him to stay retired.”

For now, he only had a thirst for Thurman and what lies ahead, this coming weekend. Performing at the highest level wasn’t new to Pacquiao after a professional career spanning almost twenty-five years. His journey had been incredible.

It wasn’t about that dramatic loss to Juan Manuel Marquez or the controversial afternoon in Australia with Jeff Horn. It was bigger than boxing.

Manny Pacquiao provides hope to those struggling in tougher, often desperate parts of the world. You could ask an eighty-year old grandmother from the Philippines if she likes sports, her first response would be to gleefully question, ‘Manny Pacquiao?’. In building new developments to ease concerns over homelessness in his native Philippines, he had become Saint-like in an entirely different fashion.

After spending time interviewing his countryman Jerwin Ancajas, a Filipino world champion who’d also risen from poverty, Pacman’s story gained additional weight. Ancajas had captured the IBF super-flyweight world title whilst completing his entire training camp at the side of a busy highway, under a mango tree in a ring defined only by faded chalk markings. This was the struggle of a fighter from the Philippines only a few years ago, in 2016 – it was difficult to imagine the challenges endured twenty years prior.

As he dances dangerously with father time, the singer, actor, basketball player, inspirational speaker, husband, father and fighter continues to break new ground. His résumé is incomparable amongst his peers, littered with excellent, conquered foes. He was smiling that night when fighting David Diaz all those years ago and still continues grinning to this day – for his people and his country. For those of us who had backed him then and in most of his fights since, the heart often rules the head.

“I am proud of my entire career. It has been a great story so far. I fight for the honour and glory of the Philippines and for Filipinos around the world. It is a big responsibility I accept with no reservation.

“Boxing has been my passion but public service is my calling. I want to be an example for giving, for doing my fair share in philanthropy.”

Interview written by: Craig Scott

Follow Craig on Twitter at: @craigscott209